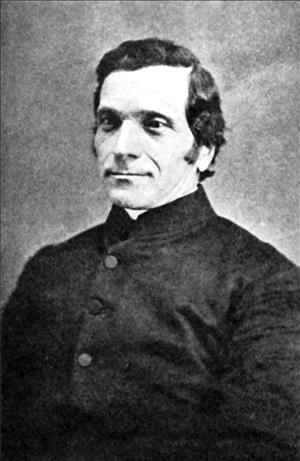

Catholic missionary Eugene Casimir Chirouse, Oblates of Mary Immaculate (O.M.I.), traveled from his native France to Oregon Territory with four Missionary Oblates and, after an arduous trip, arrived at Fort Walla Walla on October 5, 1847 -- only a month before the Whitman Massacre. Chirouse was ordained with Charles M. Pandosy (1824-1891) at Fort Walla Walla on January 2, 1848, the first Catholic ordination in what would become the state of Washington. Father Chirouse lived and worked among the Yakamas from 1848-1856 and for a short time was missionary to the Cayuse tribe. The Oblates attempted peacemaking during the tensions that culminated in the Yakama Indian War, but in 1857 were transferred to Olympia for their safety. Chirouse was assigned to oversee Puget Sound tribes and lived on the Tulalip reservation from 1857 to 1878. Here he established a school and church, the Mission of St. Anne, and helped to build missions on the Lummi and Port Madison reservations. Father Chirouse was a master of Salish dialects, translating the scriptures, authoring a grammar and a catechism, and creating an English-Salish/Salish-English dictionary. In his advancing years, the well-loved priest was transferred to a post in British Columbia, despite protests from his Tulalip parishioners. He returned to Tulalip many times to visit friends and to perform weddings and baptisms. Father Chirouse died in British Columbia in 1892.

Setting the Stage

A diverse number of reasons -- political, economic and social -- brought explorers and settlers to the Pacific Northwest. By the time the Oblates of Mary Immaculate arrived in the Oregon Territory, fur trappers, the military, Protestant missionaries, and Catholic bishops had preceded them. Traveling from Canada with parties of the Hudson’s Bay Company, Father Francois (or Francis) N. Blanchet (1795-1883) and the Rev. Modeste Demers (1809-1871) arrived at Fort Vancouver in 1838, the first Catholic priests to establish themselves in what eventually became Washington. Four years earlier, the Methodist Episcopal Church had sent Jason Lee and four others to Fort Vancouver on the Columbia River.

Much of the missionary passion to Christianize the West is attributed to one event. In 1831, four Indians (possibly Nez Perce) traveled from west of the Rocky Mountains to St. Louis to meet with explorer William Clark (1770-1838), Superintendent of Indian Affairs. They asked to learn more about the white man’s religion. What was actually said in that meeting has been largely lost in translation; the varying written accounts at the time of the meeting are well examined in Albert Furtwanlger’s Bringing Indians to the Book, published in 2005.

Whatever was actually said, both Catholics and Protestants interpreted the Indians’ visit as a call to send missionaries to the Far West. Protestants issued a long account of the Indians’ visit that appeared on the front page of the Christian Advocate in 1833. Bishop of the Saint Louis Diocese, Joseph Rosati (1789-1843) mentioned the visitation at the end of his yearly report to the mission society of France, which was published in the Annales of the Propagation de la Foi in December of 1831. A few years later, Rosati’s letter was read by a teenage boy in southeastern France. It changed his life.

Chirouse’s Early Years

The youngest of five children, Eugene Casimir Chirouse was born on May 8, 1821, in Bourge-de-Peage, France -- between the Alps and the Isere River -- about 50 miles from Lyons. His mother died during his birth, and the children were raised by their grandmother. Born of a farming family, Eugene was apprenticed as a hat maker at 15 years of age. Bishop Rosati’s letter impressed the young Chirouse and he decided to become a priest among the natives in the U.S. West.

For the next five years he studied at Crozad College in l’Ozier and Notre Dame de Lumieres Juniorate. He then began his novitiate (probation period) at Notre Dame de l’Ozier with the Oblates of Mary Immaculate, O. M. I., founded in 1816 in Marseilles.

To Oregon Territory

Chirouse was chosen as one of five Missionary Oblates to travel with Father Pascal Ricard from France to Oregon Territory. The group included Charles M. Pandosy, Clestin (or Celestin) Verney, and George Blanchet. Among them they had only enough money to travel to New York and arrived there in April 1847. They were instructed to get to Canada to meet Father Augustin Magloire Alexandre Blanchet (1797-1887), but bad weather and slow communication delayed their departure long enough for them to receive word that Blanchet had been made Bishop of Walla Walla. The group traveled to meet him in St. Louis, and together they set out for Walla Walla.

Not only was the sea voyage to North America unusually rough, but the journey to the Far West was arduous. From New York they traveled by stagecoach and ship, arriving in St. Louis on April 16. The Oblates were not warmly welcomed by Blanchet who, to the Oblates, seemed more concerned about expenses than the mission at hand. Blanchet had expected only two Oblates and now would have to find accommodations for five. Unsure of their final placement, on May 11, 1847, the Oblates set forth on the 2,000-mile journey from Westport, Kansas, to Walla Walla, following the Oregon Trail.

Toward the end of the journey the party split, with Bishop A. M. A. Blanchet heading for his new see at Fort Hall in Idaho. Father Ricard and Brother George Blanchet arrived at Fort Walla Walla on September 5. Verney, Pandosy, and Chirouse got there on October 5, 1847. The Indian population in Oregon Territory then comprised about 110,000 persons with around 6,000 believed to be Catholics.

Upon arrival, Ricard and Blanchet began building a mission, hoping to have accommodations ready as winter approached. Chief Peo-peo-mox-mox allowed them to build among the Walla Wallas, and a crude hut called St. Rose Mission was completed in October 1847.

Difficulties and Hardships

The Oblates were ill-equipped for the work ahead of them: Hierarchy within the order had yet to be defined, none had experience living in the wilderness, Protestant missionaries established in the area resented them, and they had no money. They were vaguely assigned to work among the Walla Walla, Cayuse, Yakama, and Kittitas tribes, but events soon played a defining role in their mission policy.

It was a perilous time. On November 29, 1847, Dr. Marcus Whitman (1802-1847), his wife Narcissa Prentiss Whitman (1808-1847) and 12 others were killed by members of the Cayuse tribe, and a number of others were taken as prisoners. The Catholic fathers and missionaries were now called upon to be peacemakers.

Amidst the turmoil, Chirouse and Pandosy were ordained in Walla Walla on January 2, 1848, in a simple ceremony by Bishop A. M. A. Blanchet in a one-room dwelling that served as living quarters and chapel, the first ordination in what is now Washington. Five hours after the ordination, Father Chirouse returned to his work at the Mission of St. Rose and Father Pandosy to St. Mary’s with the Yakama and Kittitas tribes.

Fathers Chirouse and Pandosy, Brothers Verney and George Blanchet and two workmen completed construction of the Immaculate Conception Mission on July 6, 1848, then began building Saint Joseph of Simcoe Mission on Yakama land and a month later Holy Cross of Simcoe. By year’s end, they had completed four missions and a superior’s residence, all very crude structures, but with good locations. No contractual agreements were involved in the building of these missions, and the Oblates took advantage of the Donation Land Act, with Ricard claiming land in Thurston County for St. Joseph of Olympia and Chirouse filing for St. Rose Mission in Yakama territory. Pandosy filed for Immaculate Conception in Lewis County.

The Yakamas had not taken part in the Cayuse hostilities, yet tensions began to build. As a result both Chirouse and Pandosy were removed to The Dalles for a time, returning to their Yakama missions in October 1848. Chirouse was made Superior of the Oblates in Eastern Washington.

The Indian Wars

During the 1850s, settlers began populating the Walla Walla territory -- Walla Walla County was formed on April 25, 1854 -- and Fathers Chirouse and Pandosy ministered to the Catholics. Among the arrivals to the territory were miners and soldiers, many of whom were suspicious of the priests’ closeness to the tribes. On the other hand, Indians suspected that the priests and new settlers were allies. The priests attempted to be the bridging peacemakers.

Survey work done for the Northern Pacific Railroad stirred great unrest among the tribes and Yakama Chief Kamiakin (ca. 1800-1877) -- once a friend to the Catholic fathers -- turned hostile. Pandosy traveled to Olympia to warn the acting governor, Charles H. Mason (1830-1899), that Kamiakin was agitating among the Indians. This was followed by news that Indian Subagent Andrew Jackson Bolon had been murdered on September 23, 1855, after meeting with Kamiakin. Hostilities between the Yakamas and whites erupted in October 1855 in what later was called the Yakama Indian War. Facing advancing U.S. troops, both Indian families and missionaries fled, leaving Native warriors to guard the mission. They were no match for the soldiers who quelled the uprising and set fire to St. Joseph’s Mission. Chirouse wrote to Father Ricard:

“All of the country is on fire. One only hears of battles, murders, plundering, burnings … As yet none of us have been killed, but we do not know from day to day … The bad Indians call us the allies of the Americans, and plan evil projects … I have not been able to get any news of our other Fathers. Rumor has it that Father Pandosy has been killed. Several people say so! Can it be true? For fifteen days I have not slept. Shall I be able to sleep tonight any better? Pray for us” (Sullivan, 29).

Pandosy indeed survived, and Father Chirouse nursed him back to health. In September 1849, Chirouse accompanied him to the Holy Cross Mission in the Yakima Valley. The two fathers had similar teaching approaches, and both had a passionate interest in learning the indigenous languages. Chirouse was taught first by Peter Patatis, an Indian who spoke some French, having traveled with the Hudson’s Bay Company. Both fathers incorporated native dialect into their services.

Peace remained fragile. On December 8, 1856, Chirouse left St. Anne’s, having been called to Olympia. By 1858 all of the Oblates were withdrawn from Eastern Washington. Five of the seven Missionary Oblates originally assigned to Washington Territory were transferred to Canada. Father Chirouse was assigned to oversee the Puget Sound region and was based at Tulalip Bay.

Scouting Puget Sound

The Missionary Oblates found Puget Sound an easier location for their mission. The climate was moderate and the tribes welcomed them. Following the Point Elliott Treaty signing in 1855, the Oblates made several scouting voyages in the region, the first from July 22, 1855, to August 17, 1855, where they met with Snoqualmie, Snohomish, Skagit, and Lummi tribes. On a second voyage -- August 23 to September 1856 -- they met with smaller tribes and connected with Chief Seattle (178?-1866), who arranged for the third visit, an extended stay in October on the Port Madison reservation.

Father Chirouse and Brother Philip Surel made a fourth voyage around Puget Sound -- July 25 to November 10, 1857 -- on which they “visited 20 tribes, blessed 109 marriages, baptized 500, heard 2,000 confessions, added 209 catechumens to the baptismal registry and planted ten mission crosses among the natives" (Young, p. 136). So successful was this voyage that Father Chirouse, Father Paul Durieu (1830-1899) and Brother Clestin (or Celestin) Verney were assigned to a permanent mission with the Snohomish on Tulalip Bay. Though times would continue to be hard, with little money to support their efforts, given the Oblates almost unimaginable poverty and danger in Eastern Washington, their struggles in Puget Sound must have seemed small by comparison.

Chirouse’s Long Stay at Tulalip

Chief Sehiamkin (Charles Jules) of Tulalip told his personal story of Father Chirouse’s arrival. According to Jules, the priest came to the reservation in 1857 and, through an interpreter, asked permission of Jules's uncle, chief of the Snohomish, to live among them. A council met, the priest was welcomed, and they helped choose a spot on Ebey Slough to build a house. This location later became known as Priest’s Point. Chirouse soon was joined by Father Durieu and Brother Celestine.

The missionaries constructed a log house, which served as residence, church, and school, and called it the Mission of St. Anne’s. At first it was a day-school only with 11 students -- six boys and five girls. In a year’s time the priests moved nearer to the point itself and built a larger structure that would accommodate a boys' boarding school. By 1860, the school had 15 students, including students from other parts of Puget Sound.

Chirouse’s work was not confined to Tulalip. He traveled widely by canoe, even to Canada, where on one occasion he baptized 400 children on Vancouver Island. A frequent visitor among Puget Sound tribes, Chirouse was called to deliver the last rites to Chief Seattle on the Suquamish Reservation at Port Madison at 1 p.m. on June 7, 1866.

Within the Oblate structure, Father Chirouse now served under Bishop A. M. A. Blanchet, who resided at Vancouver in Clarke (later "Clark") County, Washington Territory. And although Chirouse’s base was Tulalip, his parish included the Lummi, Muckleshoot, and Port Madison reservations. With the help of Father Durieu and Brother Verney, he also attempted to reach non-reservation Indians.

Making Do

Territorial Indian Agent Michael T. Simmons (1814-1867) officially established the Tulalip Reservation in 1860, and Father Eugene Casimir Chirouse became the first incumbent agent, soon yielding to Samuel D. Howe, the first appointed regular reservation agent.

With few resources, the missionaries needed to be innovative. One story tells of Father Chirouse preparing to meet Bishop Magloire Strainer, making himself a cassock from a white wool blanket, which he dyed black by using blackberry juice. Traveling by boat, Chirouse and his oarsmen encountered a storm and the boat capsized. They were able to right the boat, but the saltwater faded the cassock to violet, the color of a bishop’s attire. The boat capsized again and this time the saltwater returned Chirouse’s cassock to white, the color worn only by the Pope. Camping that night, the party luckily found enough blackberries to re-dye Chirouse’s cassock, so the father was able to meet the bishop dressed in the appropriate priest’s black.

The Mission School Grows

The school of St. Anne’s grew even though adequate government funding did not come. Chirouse provided free schooling -- food, clothing, and education -- only by raising money himself. When some government financial aid finally was given in 1861, the annual sum was still so small that extra funds had to be found. Chirouse filed a report on July 1, 1861, stating:

“Up to the present time, I have myself supported the school, and have paid $200.00 for books, clothing, etc., and $400.00 for clearing and fencing the grounds. I was assured by Mr. Simmons, the late agent, that I would be reimbursed for these expenditures by the Indian department, and trust that such will be the case ...” (Sullivan, 48).

By 1861 -- the same year Snohomish County was formed -- the priests and their students had cleared four acres of land at Tulalip, no easy task since it first needed to be logged. They had built cabins, as well as the mission church of St. Anne’s. That year Chirouse also helped build churches on the Lummi and Port Madison reservations.

They planted a large garden and orchard. But since produce alone could not provide sufficient food for the students, most joined their families in fishing for part of the year. Father Chirouse sought to build a better boarding school. Enrollment increased and government reports repeatedly showed that the Tulalip School was highly successful. Tulalip Agent S. D. Howe requested that the government build a new schoolhouse, adding:

“I am at present clearing off a site for such a purpose ... Father Chirouse has a large influence among the Indians ... . He is peculiarly fitted for their instruction. This school should receive the fostering care of the Government” (Sullivan, 50).

Enough federal money was given in 1863 to build a boys’ dormitory on Tulalip Bay and a house for Father Chirouse and Brother Mac Stay. In a report to Agent Howe in August of that year, Chirouse requested a good seine, which he felt would help his students catch fish more efficiently and thus save their school time.

Chirouse remained hopeful regarding the school’s growth, and in 1868 invited the Sisters of Charity of Providence (Montreal) to establish a girls’ school at St. Anne’s. Federal support was given for this the following year, making St. Anne’s Mission at Tulalip the first contract Indian school in the nation.

Chirouse continued to conduct services around Puget Sound, sometimes speaking to audiences as large as a thousand people. By 1868 the Oblate Fathers in the region had baptized 3,811 people. The following year Father Durieu was elevated to the position of Bishop and Father Pierre Richard filled his position at Tulalip.

Many Duties

Numerous accounts relate Chirouse’s linguistic talents. He quickly learned the Coast Salish dialects and compiled a Snohomish-English and English-Snohomish dictionary. He preached his services in both English and Snohomish and also translated bible stories and prayers into Snohomish. He began a boys’ choir and a band, obtaining instruments from troops in the region. Traveling by canoe, the Oblates and the young musicians raised money by giving performances to settlers, loggers, and mill workers.

Father Chirouse was once again called upon to be peacemaker, this time between the Indians and the federal government. The tribes’ great frustration over broken promises worsened when settlers and lumbermen began infringing upon reservation boundaries. The tribes also had expected medical aid as part of the treaty promise, yet none had come. Chirouse bought medical supplies from his own meager pay. During an 1862 smallpox epidemic that killed half of the Native American population from Victoria to Alaska, Fathers Chirouse and Durieu vaccinated several thousand Indians in the Puget Sound region, saving many lives.

More Lean Years

The U.S. government’s intention regarding Indian education was to assimilate Indians into the melting pot of America. Boarding schools, which separated students from their families, speeded acculturation. The church’s mission was to convert them to Christianity and to change their practice of polygamy, drinking, gambling, and intertribal warring. Writing to a brother Oblate on February 15, 1860, Chirouse stated:

“There are now but few polygamists ... . The greater portion of the gamblers have renounced their impositions, and have brought to us their games which we preserve with the instruments of magic and sorcery as permanent witnesses of their promises to God. More than nine hundred young men have enrolled themselves in our temperance society ... . Formerly war decimated these poor tribes, who sought only to make slaves of one another, and now they seem to make but one people of friends and allies” (Sullivan, 46).

Regarding polygamy, tribes people recalled it differently, frequently aiding women abandoned by their mates.

But poverty remained the biggest threat to the priest’s mission. Chirouse wrote in an 1866 report:

“In the beginning of last winter, my pupils (who are all boarders) numbered 48, but having neither clothing nor provisions to furnish such a number, I was reluctantly obliged to allow some of them to return to their homes hungry and half naked. At present, there are 35 in attendance ... . During the past year, sickness has prevailed to a very great extent among the Indians of the Sound and I am sorry to say that my pupils have suffered much more than heretofore ... . As there is no doctor on the reservation, they still continue to apply to me for medicine, believing my stock inexhaustible” (Sullivan, 62).

The Point Elliott (Mukilteo) Treaty of 1855 had promised a regional school for 2,000 students and still, by 1866, the school could not support 100. Chirouse’s efforts led to glowing reports but little money. A church, a school, a road, a bridge, and cabins had been built, students were learning to speak English, and a garden had been created in the midst of a forest. The most profitable venture was operation of the Tulalip Mill, originally built and run by white settlers in 1853. It was refurbished as a Tulalip enterprise and a logging operation was established. Both provided independent work for men at Tulalip, with native people handling the sale of lumber.

But needs always exceeded accomplishments. Chirouse wrote in the same report:

“Four of my oldest and more advanced pupils left the school last spring, and are now making every effort to fix their homes on the reservation and support themselves by small farming operations. Their intentions and dispositions are as good as can be expected, but it is also to be regretted that they having spent so many years working hard at school, found themselves on leaving, without means, and deprived of all hope of assistance from the department, the one place they had to look to for support in order to get a start in life of honesty and industry. The wandering, wild children of the Sound, who have never been to school, appear far better clothed and fed, and are very naturally subjects of envy to our half naked, half starved pupils who are, as it were, doomed to a life of misery and woe, owing to their good disposition to become civilized, and to be (according to their present expectations), hereafter a credit to themselves and their posterity. Not so with the former; working as they do for the white settlers, they earn as much money as they require to supply their wants, and very often earn too much for the bad use they are taught to make of it, entailing misery on themselves and on all those with whom they have communicated. This, then, is one of the many reasons that some help, some encouragement should be awarded to these poor, well disposed children ...” (Sullivan, 62-63).

Tulalip welcomed a resident physician, finally assigned by the government to the reservation in 1867. That year a new church was built, and was blessed on its opening by Bishop A. M. A. Blanchet.

Struggles continued to take their toll on the priests, with Chirouse candidly reporting on January 7, 1868:

“Nobody pays any attention to Indian matters ... . Members of Congress understand the negro question, and talk learnedly on finance and political economy, but when the progress of settlement reaches the Indians’ home, the only question considered is ‘how best to get his lands’ ” (Sullivan, 66).

Chirouse’s Last Years

Father Chirouse had spent most of his adult life among the Indians of Washington. The work was exhausting and in his advancing years he suffered from rheumatism. Yet he resisted any lessening of his duties. In 1878, Oblate superiors called for Chirouse’s transfer to British Columbia. Those at Tulalip were saddened and even considered petitioning the Pope to change the action. But Father Chirouse yielded to the wishes of Bishop Blanchet and left for his new assignment.

Rev. John Baptiste Boulet became the resident priest at Tulalip, and Chirouse began duties as Superior of St. Mary’s Mission in Mission City, B.C. He was also made principal of its Indian school. St. Anne’s at Tulalip was now in the hands of the Sisters of Providence. Father Chirouse returned to both the Tulalip and Lummi reservations on numerous occasions to visit and to perform weddings and funerals, and a few students visited him in British Columbia.

In late December of 1891 Father Chirouse suffered a stroke and was hospitalized. But he recovered and planned to resume his work. On May 28, 1892, he suffered a fatal stroke.

Funeral services were held at St. Mary’s Mission in Mission City, and Chirouse was buried on the banks of the Fraser River, his grave marked by a small cross. A new Father Eugene Casimir Chirouse -- Chirouse’s nephew of the same name -- was now a missionary in British Columbia.

In 1901, the federal government began running the Indian boarding school at Tulalip, ushering in an era of greater cultural repression, with students being severely punished for speaking their native language and practicing tribal customs. St. Anne’s was destroyed by fire March 20, 1902, and a new school built on Tulalip Bay, operated by the government until 1932.

A new church was constructed on the site of the burned mission. It still stands and is on the National Register of Historic Places. Today special church services at the Mission of St. Anne are spoken partially in the tribes’ native language of Lushootseed, like those once given by Father Chirouse.