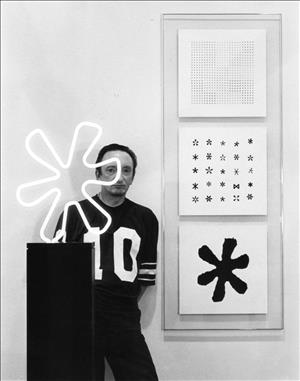

As a gallery owner, teacher, artist, and creative thinker, Don Scott was a catalyst in the Seattle arts scene from the 1960s until his premature death in 1985. While an undergraduate at the University of Washington, Scott organized Seattle's first "happening" at the Seattle Center and was hired as a curatorial assistant at the Seattle Art Museum. After graduating in 1963, he opened the most exciting art gallery in the region. Besides showcasing some of the Northwest's top artists – Leo Kenney, Margaret Tompkins, Spencer Mosely, Bob Jones, and Frank Okada, to name a few – Scott staged events to complement the exhibitions, including experimental films, chamber music, jazz, plays, poetry, even a night at a go-go dance bar. The gallery closed after just two years, but Scott remained deeply embedded in the art scene. He taught a controversial art history class at Cornish; contributed to Seattle's counterculture newspaper, Helix; painted a wall mural in Afghanistan; and collaborated with art critic (and later novelist) Tom Robbins (1932-2026) on a book, a radio play, and a decidedly anti-establishment attitude. All the while he made and exhibited his own distinctive word- and idea-driven artworks. In the 1970s, enamored with the worldview of architectural philosopher Buckminster Fuller, Scott expanded his thinking and was planning a global sister-city project when he died unexpectedly at age 53.

A Challenging Childhood

Don Scott rarely talked about his past or his personal life. Even to longtime friends, he never mentioned his father – and it's possible he never knew him. Donald George Scott was born in Sheridan, Wyoming, on January 15, 1932, to George Rozelle Scott (1909-1966) and Ruth Snodgrass Scott (1908-1977). At some point George left the family, and in the 1940 census Ruth listed herself as a widow. But George wasn't dead, and the couple did eventually divorce. Records show that he remarried and died in Texas in 1966. To Don, his father was nothing but a ghost.

In 1943, Ruth and 11-year-old Don moved to Seattle, where she found work at Boeing. They moved into an apartment on Beacon Hill and Don attended Beacon Hill Elementary through 8th grade and then Franklin High School. He was small for his age, with a slight build, and a class photo shows him looking very young and rather fragile among much-larger classmates. Don was an average, if erratic, student. If he found something that stimulated his imagination, or a teacher who inspired him, he could swing from a D in a subject one quarter to an A the next. He signed up for art classes repeatedly and also took typing, developing a lifelong fascination with the machine. He graduated from Franklin on June 16, 1950, having already enlisted in the Naval Reserve, where he learned navigation. He worked for a while at Boeing as a photographer, then, still in the reserves, Scott was accepted at Central Washington State College, now Central Washington University, and moved to Ellensburg for fall quarter, 1954.

Love and Art

He attended Central for only a year but met an attractive art student named Constance Weber (1934-2019). Although two years younger, she was ahead of Don in school, and completed her B.Ed. in 1955. Weber enrolled in the graduate program at the University of Washington that fall, and Scott, too, returned to Seattle. He spent a year at Edison Technical School, where he studied geometry while working at Foto-Typesetters, where he learned printing – a skill he would later use in his artwork and fall back on when he needed a job. A Navy publicity photo from 1956 shows Scott as a radarman second class, "one of 60 outstanding Naval Reservists" chosen for an "award cruise" to Hong Kong on the USS Roanoke. In 1957 he and Connie married, and Scott enrolled in the UW art school in 1960.

He was a leader at UW. By his junior year he was making news for his activities at school and in the community. As president of the art department's student service organization, Parnassus, Scott helped organize and publicize student exhibitions. His work and his compelling way of talking about art caught the attention of The Seattle Times's new art critic (later novelist), Tom Robbins. Robbins noted in April 1963 that Scott would be staging a happening at the Seattle Center Fairgrounds. "To the uninitiated," Robbins explained, "a 'happening' is a sort of free-for-all public art project" ("Indian Center …"). The next month, Robbins again singled out a project that Scott had set up on campus and wrote "the community is fortunate to include a young man of such drive and verve …" ("Three Sweet Notes …").

It was true: Scott projected a kind of confidence and enthusiasm that drew people in. And art school was his natural element, a place to be creative, exercise his leadership skills, and think outside the box. His senior year, Scott was hired parttime at Seattle Art Museum as a curatorial assistant, and he continued to work at the museum for a while after graduating in 1963.

Plans were in the works at the former Century 21 site for a Northwest Craft Center, and Scott applied for the manager's job. When a more experienced candidate, Ruth Nomura (1932-2020), was selected over him, Scott decided to open his own art space. "He had a real urge to have a gallery and wanted it to be the top gallery," Seattle historian Paul Dorpat (b. 1938) recalled. "He became known for it very quickly" (Dorpat interview). Architect Gene Zema (1926-1921) offered Scott a handsomely designed former living space at 200 E. Boston to house the gallery. Scott recruited some UW professors – Bob Jones, Alden Mason, Spencer Mosely – and invited other prominent artists to join, including Leo Kenney, Frank Okada, Margaret Tompkins, and James Fitzgerald. He opened with a group show in September 1963. In a glowing review for the Times, Robbins described the place as a "beautiful modern gallery where John Q. Mediocrity is persona non grata" ("Scott Offers Strong Art …").

Scott wanted his gallery to be more than a showroom and enlisted some of Seattle's top talent to help make it a cultural hub. He partnered with Boyd Grafmyre (1940-2019) – soon to become Seattle's preeminent rock music promoter – to line up a series of events, including the Henry Siegl Quartet, Seattle Contemporary Jazz, and New Dimensions in Music. Robbins hosted an evening of experimental films. Actors Tom Wilson, John Gilbert, and Stillman Moss (of the newly formed Seattle Rep) performed short plays by Samuel Beckett and Edward Albee. There were poetry readings, and the series culminated with a bus transporting mystified art patrons to a go-go bar to party. The gallery also stood out for its distinctive mailers. For each show, Scott designed a different style of announcement. Some unfolded to serve as posters, some were multifold cards, each was unique – some a bit cheeky or outrageous – adding to the gallery's aura of experimentation.

All that energy didn't translate into financial success, however. Scott had a relaxed attitude about money and would often ask his mother for funds. Throughout his life he turned to friends or his older cousin, Delos Snodgrass, to help pay for creative projects. Connie, with a job teaching junior high art classes, must have felt the pinch, too. Even though on paper Scott's career was taking off, there were problems. At some point, probably in 1963, Don and Connie separated. Their divorce was final by June 1964, with Scott owing her $250. Scott simply moved on and didn't talk much about Connie or his marriage after that. It wasn't openly discussed in those days, but as time went by Scott's friends knew he was gay.

Moving On

Just a year after the gallery opened, Scott and Zema got into a dispute and Zema told him to move out. (Zema and his wife opened their own gallery in the space, called Atrium.) Scott quickly found another space, at 2920 Eastlake Ave E, not far from the Red Robin Tavern. His new business card listed him and Grafmyre as co-directors. Robbins remained a supporter: "When Don Scott opened his gallery last year, one knew immediately that here was a mighty force in the war against complacency, and Scott has maintained his high ideals and dedication to originality and strength" ("Gallery is Esthetic Supermarket"). Around this time Scott designed and published Collaboration, an elegant, boxed book featuring Jerrold Ballaine's artwork with poetry by David Charles Fields, selling it in advance by subscription to pay expenses. In October 1964 Scott and Robbins produced and performed a radio play they had cowritten, "Northwest Art: A Musical Tragedy," for KRAB FM and later that month Scott began hosting his own radio show "Talking About Art," for KING FM.

Just a year later, Scott Galleries, no doubt losing money, abruptly closed. By then, Scott was well into a publishing scheme with Robbins, who had left The Seattle Times. They were working on a book about Northwest artist Guy Anderson, to be the first of a series of regional art books they planned to produce. Written by Robbins (his first book) and designed by Scott, Guy Anderson would have photographs by Bob Peterson (1941-2022) – later a prominent photographer for LIFE magazine and other publications – and include a full-color reproduction that could be removed and framed. They offered the book at a special presale price of $2.50, using advance sales to pay their printing costs. It was an appealing idea but apparently not a profitable business plan: The series ended with the first book. Robbins's next writing project, the novel Another Roadside Attraction, would prove considerably more successful.

Scott moved on to other adventures, too. Always excited about the latest technology, he projected an early version of a light show for a concert at Cornish School of Allied Arts manipulating inks and water on a slide projector as the musicians played. Then he set out for a long working vacation. Invited to stay with a friend in Marblehead, Massachusetts, for the summer, Scott left for destinations on the East Coast, stopping in New York and Boston, sending giddy postcards to his mother along the route. Ensconced at his friend's house in Marblehead, he bought a green Raleigh sports bike with a rack to hold his typewriter and rode off to the beach, where he typed letters and a series of postcards that he sent in mass quantities to friends. He saw the cards as an art project, but not everybody got it. "My post card bit seems to be a bit confusing to some people," he wrote to his mom, "but others are picking up on it so I am getting some really nifty things back in the mail" (Letter, Don Scott to Ruth Scott);

He was working on another book, too, handmade in an edition of 10. Grey, A Portrait of Today, was "a sort of adult ABC book," he told his mother. Scott wrote the text and designed the pages, typography, and color scheme, reporting, "thus far, I am extremely happy with it" (Letter, Don Scott to Ruth Scott). He added that he thought the postcards would be important, too, "so keep them."

Kandahar

Bigger travel plans were looming. Scott had booked passage on a ship from New York to Karachi, Pakistan, leaving September 6, 1966. From there he would catch a train to Afghanistan and a bus to Kandahar, where he'd be staying with a friend in the Peace Corps. The journey would take 32 days and was paid for by a "private grant" (Resume, Don Scott personal papers). In Kandahar the walls of his room provided the canvas for his next art project. It began with a life-changing epiphany, likely enhanced by the local hashish. As Scott watched the changing patterns of sunlight on the walls, he began painting them in a multicolor design that leapt and splintered across the hall, ceiling and archways of the apartment. He called it A Four or More Dimensional Kinetically Controlled Environmental Awareness in Collaboration with the Sun. It was, he wrote, "a personal revelation to me of a very prime nature" (Letter, Don Scott to Ruth Scott).

To celebrate the mural's completion, he and his host, Steve Smith, threw a party, complete with live music and martinis, for about 40 people. Half of them were Americans in the Peace Corps or government jobs and the other half Afghans, including the governor of Kandahar Province, who was apparently impressed with Scott's work. "Mother, so many strange and beautiful things have happened since I saw you that I couldn't begin to put them into letters," he wrote, signing off, "I love you Mother" (Letter, Don Scott to Ruth Scott).

Teaching and Inspiring

By June 1967 Scott was on his way back to Seattle. He typed up an account of his mural project in Kandahar, which the Seattle Post-Intelligencer published in its Sunday magazine in a centerfold spread with photos. Scott wrote that as he sat gazing at the sunlight pattern on his wall, "for the first time in my life my mind was free of either anticipation or apprehension, and I felt as if I were looking straight into NOW …" ("The Indifference of the Sun …"). That fall, Scott began teaching design and art history at Cornish School of Allied Arts (now Cornish College of the Arts).

In 1968 Scott designed and produced another limited-edition boxed book of visual and verbal poetry titled Dispersal (or Clear) that took its cover image from the I Ching. The Times called it "an imaginative, iconoclastic, and brilliant little book," when Scott exhibited it at the Attica Gallery ("Guy Anderson Paintings …”); Paul Dorpat, then-editor of the counterculture newspaper the Helix, devoted an entire page to promoting it, with a full-frontal nude photograph of Scott in the center ("a vigintillion in numbers is"). The following summer, Helix gave Scott a double-page spread for his account of climbing to the summit of Mount Rainier. Scott designed the pages and titled his essay, "How High I Got on 7-11-69" (Helix, July 31, 1969, pp. 12-13)

At Cornish, Scott was pushing his students to think outside the box and devised all kinds of prompts and projects to make that happen. Inspired by his mural project in Kandahar, he proposed the class paint a mural on the walls of the Cornish theater. Initially, the idea was approved by the administration, but once the mural started growing, with a peace dove in the corner of the room and the stenciled word "Ecology," the higher-ups had second thoughts and asked Scott to remove it. Scott refused – and quit. Cornish director Fred Patterson told the media, "I have a lot of respect for Don, but his own creative energies and convictions often blinded him to the viewpoint of others" ("Don Scott Quits …"). Several students in Scott's class, including the future gallery owner Bill Traver, paid Scott's tuition so he could enroll as a student and continue teaching them. Part of their assignment was to hand-make an edition of 12 large canvas-bound books commemorating the class. The class also staged a happening, which they dubbed a "Blivit."

During that time, Scott, always a lively interview, was one of five artists featured on a KCTS TV program hosted by Anne Focke (b. 1945). "Don was such a catalyst," his friend, painter Albert Fisher, recalled. "He was tremendous talking about art. To be agreeable wasn't the point; we wanted differences ..." (Farr interview).

Bucky

Now jobless, Scott found another focus for his energy: Buckminster Fuller (1895-1983). The inventor and architectural philosopher who conceived the geodesic dome as the living space of the future, Fuller hosted events called World Games, intended to promote a design-science approach to global problems. Scott was all in. For the next couple years he lived an itinerant life, mostly devoted to Fuller, attending his World Game at Southern Illinois University (where Scott registered for the workshop as an Aesthetic Anarchist) and in San Francisco, where he was invited to participate as a designer. With next to no income and on the move, Scott got used to crashing with friends, enjoying whatever meals and mind-altering substances were at hand, and continually scrambling for money. He worked on a 3-minute animated film and got Fuller to add a line to a postcard which, for a $2 donation, Scott would send by mail. He occasionally came back to Seattle to exhibit some of his latest idea-driven artworks at various galleries, including Attica on Broadway and Manolides in Pioneer Square.

Then, for Festival '72 (the precursor to Bumbershoot), Scott, in full Bucky Fuller mode, was invited to construct a grand, walk-through Tetrahedron at the Seattle Center, built with help from UW architecture students. That was also the year he introduced a concept that would drive his projects for the rest of his life: the benchmark. Like the actual geological place markers, Scott's were small cast-bronze disks, but instead of marking the latitude and longitude, the first limited-edition series was designed to be portable, stating simply "Optional" and "Relative." For Scott, the benchmark, altered in various ways to reflect a cosmic rather than an earth-bound perspective, became his emblem of an expanded way of thinking.

In addition, he had begun using the most advanced typewriter of the time, the IBM Selectric, to produce artworks entirely composed of typed words, the words creating an image of the meaning they expressed. The work was elegant and cutting-edge, but a bit far out for critics with more traditional taste. Scott's 1972 show at Gallery East, which included the first benchmark and his graphic "Field and Stream," received a tepid review from John Voorhees, who found the benchmark "amusing" and the show "not terribly interesting" ("Add Conceptual Art …").

Travel and Tragedy

In need of cash and wanting to "regroup his thoughts and bask in the northern lights" ("His Art is Word Play"), Scott took a job as a printer in Anchorage for a couple of years. He continued his travels to Fuller events, as well as a design conference in Aspen, where he met up with his old Seattle pals Anne Focke, Bert Garner (1940-2015) Bob Teeple (b. 1941) and Ken Leback (b. 1941). The group jokingly dubbed themselves the Seattle Souvenir Service, devoted to collecting and exhibiting kitschy Space Needle memorabilia. They also began formulating plans for what would soon become Seattle's preeminent artist-run alternative art space – and/or gallery. It opened on Capitol Hill in 1974.

In March 1976 Scott was back in Seattle to install a one-person show of his graphics at and/or. Then, in April 1977, chasing the latest technology, he attended the First Annual Computer Faire in San Francisco, keeping a souvenir printout of a pixilated image of his face to mark his participation in that groundbreaking exposition.

That summer, Scott's personal world was upended when his mother died of pneumonia. She had always been his anchor. Although Scott made friends often and easily, few knew much about him. He was proud of living in the moment, a man of ideas and action, who rarely shared his feelings. Ruth had been his greatest supporter, both emotionally and financially. Now he was on his own.

Art Shows and Odd Jobs

During that summer, Bill Traver (b. 1942) was formulating plans to open a gallery in Belltown that would represent two of his former Cornish instructors, Scott and Paul Heald (1936-2014). The gallery opened with a group show in September 1977. That fall Scott's work was also included in an exhibition at Central Washington University. While there for the opening, Scott arranged a meeting with his former wife, Connie Weber (Speth), now remarried and a professor in the art department where she and Don had first met. Scott apologized for past hurts and paid her the money he had long owed her. After so many years, hard feelings were finally left behind.

In March 1978 Scott's career was spotlighted in a one-man show at Traver Gallery and a retrospective at and/or. There, two walls papered with some 1400 of Scott's postcards mesmerized viewers, alongside some of his larger typewriter pieces, Mary Randlett photographs of Scott at his former gallery, and examples his handmade books. Arts writer Jean Metzger called the graphic work, "a cool, intellectual, yet simple and beautiful art of letters and words" ("His Art is Word Play"). Dorpat touted Scott as "a civic treasure with a cosmic calling to fight those deadly serious agents of chaos and entropic sameness" ("The 'Crazy' Artist …"). Meanwhile, Scott was working as a dishwasher to support himself.

The fall of '78 brought another new art showcase to the city: the Richard Hines Gallery, devoted to selling high-end art by artists from New York and Los Angeles, including Robert Rauschenberg, Ed Ruscha, Richard Serra, Bruce Nauman and Michael Heizer. Hines, a 29-year-old art collector, wanted to offer a broader context to the artworks being shown locally. Conversations with Scott over the years, and Scott's 1980 exhibit of benchmarks at Traver Gallery, piqued Hines interest in Scott's latest project: Placing a series of benchmarks along the Washington state coastline and documenting the installations as he went. "I loved the concept of a monumental sculpture, minimally altering the environment, along the lines of Walter de Maria," Hines recalled (Farr interview). In 1981 he offered Scott a small show in a side gallery, which included a granite stone with a bronze benchmark, color xeroxes documenting the installation process, and 12 framed photographic prints of the 12 benchmark sites. "Of course, the show was not a commercial success in any way," Hines said (Farr interview).

For Scott, though, the show was a huge milestone. It placed his work at a prestigious gallery among some of the top artists in the country. It validated him as a conceptual and environmental artist of significance, even though his work was not being shown or collected by local museums. And it gave a boost to other likeminded artists of the region. "We all felt lifted by that experience, that Hines opened his gallery for Don and his work being exposed," Leback recalled. "That was gratifying for us," (Farr interview.) The exhibition, titled "From Hoh to Shi Shi" was the high-point of Scott's career – and it also marked the beginning of its decline.

The Decline

The publicity from the exhibition drew attention to the fact that Scott had been placing benchmarks in National Parks (and around Seattle) without permission. A threatening letter from the Department of the Interior forced Scott to retrace his hikes and remove the benchmarks (documenting that process as well). The lack of sales was a setback, too. Scott had to face the fact that his conceptual artwork wasn't suited to a commercial gallery. Hines didn't schedule another show for Scott, and in 1983, finding the business unprofitable, he closed the gallery. Traver, too, was struggling to keep his gallery afloat and turned to the hot market for Pilchuck glass art to help pay the bills.

Nevertheless, Scott seemed upbeat, looking as always toward bigger things ahead. He designed a public art installation with his old pals Leback and Garner, a project that later fell through. And in 1984 he installed a window display at Art in Form bookstore. The title, "AIDS to navigation," referenced the epidemic and Scott's days in the Navy, yet the installation itself was abstract and enigmatic, with simple geometric forms and mirrored squares in each window to reflect any onlooker. Nobody suspected it would be Scott's last exhibition. He was percolating a plan for installing a far-flung environmental artwork called Seattle Geocentric Sister City Analog, which would encompass a central monument located in Seattle, and stone sculptures with benchmarks to be installed in 11 sister cities around the globe. He hadn't yet found funding for the project when, in March 1985, while crossing the Seattle Center at night, Scott was assaulted and badly beaten up, his body bruised, his nose and both cheekbones broken.

Leback remembers Scott struggling to regain his optimism afterwards, even after he recovered from his injuries. Then in late summer Scott was feeling feverish and exhausted and Leback urged him to see a doctor. Scott deferred. He did tell friends he got an HIV test, which was negative. When Scott's condition became more serious, Leback pushed to take him to the nearest ER. Scott finally relented but asked Leback to drop him off in north Seattle at Waldo Hospital, a former Osteopathic facility. He died that night. An autopsy determined that lung cancer was an underlying cause of his heart failure.

Farewell

In a touching obituary, Scott's old friend Walt Crowley (1947-2007), a founder of HistoryLink.org, wrote: "Most of us … live on a flat Earth. Don Scott lived on a sphere. As the citizen of a round planet, Don understood that horizons and sunsets are illusions, that space and time have no real limits, that energy radiates outward for eternity. His art was dedicated to illustrating these principles, and his life and effect on those who knew him are their proof" ("Don Scott, Navigator …").

Two of Scott's friends, Pennie Pickering and Steve Rottler, purchased the rights to the Sister Cities project from Scott's estate to keep the plan alive. In 1988, they worked through official channels to install a stone and benchmark in Tashkent, Uzbekistan. Then in 1993, Pickering arranged with Seattle artist Michael McCafferty to complete an installation in Galway, Ireland. In 2024, efforts were underway to organize an exhibition and find a permanent home for Scott's archive.