Wilbur is a town in Lincoln County, 21 miles southeast of Grand Coulee Dam and 65 miles west of Spokane. Samuel Wilbur Condit (1833-1895) was the first non-Native settler in the area, and it was Condit – nicknamed Wild Goose Bill – who platted Wilbur in 1889. Fires in 1891 and 1901 destroyed much of the town, but its residents rebuilt both times. Sustained by the wheat industry for much of its existence, Wilbur's population peaked at nearly 1,200 in the 1960s. Marion Hay, who settled in Wilbur in 1889, a year before incorporation, became Washington's seventh governor in 1909.

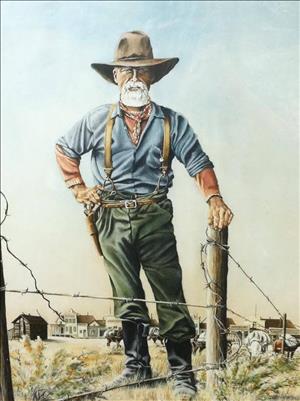

Wild Goose Bill

Any history of Wilbur begins with Samuel Wilbur Condit (his name also appears as Condon), a New Jersey native who came to Washington Territory via California in about 1856 to haul goods from Walla Walla to mining camps and settlements in North Central Washington. After being on the go for two decades, Condit settled down in 1875 "on the flat land between the bluffs near Goose Creek, on the site that is now Wilbur" ("History of Wilbur"). According to a 1988 retrospective in the Wilbur Register:

"When Condit first arrived at his valley, the land was unsurveyed, but he staked his claim. Later, Condit acquired title from the United States government to the land on which the Town of Wilbur now stands. After the mineral discoveries at Ruby City and Conconully, the area grew as miners and others moved in. The railroad had been completed to Sprague by 1883, and this helped to settle the country. Condit's ranch was the stop-over point along the route to the north for those with wagons or riding horses, or even walking" (Hinkins).

Legend holds that Condit earned his nickname after he shot into a settler's flock of geese. According to an account written in 1912 by Major R. D. Gwydir, an Indian Agent in Wilbur:

"Condit won his sobriquet by firing into a large flock of tame geese owned by a settler between Walla Walla and Colville under the impression they were wild. The owner of the flock had brought the eggs all the way from Oregon and was so indignant over the loss that she followed Bill to his home, delivering all the way a scathing tirade against the stupidity of a man who pretended to be a frontiersman and didn't know the difference between a wild goose and a tame one" ("Wild Goose Bill ...").

Fortunately for Wild Goose Bill, he was more adept with horses and cattle, raising them on his ranch. He found several other ways to make money. "He expanded his business enterprises, developing a road to the mines in the north, a ferry across the Columbia River, and a supply system to sell merchandise to the pioneers and miners, as well as to the local Indians" ("History"). Meanwhile, a community began to grow on his property. "By the late 1880s, a number of other people had joined him at his ranch along Goose Creek, but Wilbur's real boom began in 1888 when it was learned that the Central Washington Railroad [a spur of the Northern Pacific] would go through the town. The following year the town site was platted. Three sawmills were kept running at peak capacity, but still the supply of lumber was inadequate to meet the needs of the rapidly growing community" ("History of Wilbur").

Negotiating with railroad officials, Condit agreed to deed half-interest in his original property and his subsequent additions to the Central Washington Railroad. In return, he would share in proceeds from sales made by the railroad, which promised to locate a depot on the original townsite by the end of 1889. "Thus the management of the Wilbur townsite passed into the hands of a company of energetic men who possessed ample capital and vim with which to develop the resources of the town" (Steele and Rose, 146). On May 25, 1889, the Wilbur Register reported that "five new buildings have been completed within the past week; six more are in course of construction and lumber is being hauled on to the grounds of several others. There is no doubting the success of Wilbur. A grand and glorious future is already secure" (quoted in Steele and Rose, 146).

A fire on October 4, 1891, put a grim halt to progress. A kerosene lamp, left burning in the home of Damian Wagner on Main Street, exploded. The flames spread quickly, consuming the house and destroying several nearby buildings. Despite heroic efforts by Wagner and his wife Christina, three of their children – Charlie, 4; Robert, 6; and Annie, 10 – died in the inferno. "Mr. Wagner then quitted the building only to learn that his wife had perished, and the scene was touching and heart-rending" (Steele and Rose, 151).

Frontier Medicine, Frontier Justice

A doctor, Baldwin "B. H." Yount, arrived in 1886. For a time, he and his wife lived on Condit's property "in a board shack with a dirt floor and mud dripping into the little room during the infrequent rains" ("Histories of Wilbur & Sherman"). Yount cared for patients "from a distance of 25 miles or more. Year after year he served Wilbur and the surrounding territory beyond – bordered by Creston on the east, Coulee City on the west, Wilson Creek on the south, and Keller on the north. Doctor Yount also served as official physician for the Northern Pacific Railway Company in the Wilbur area until the time of his death. His son, Dr. Glen Yount, carried on his practice until he too, died following World War II" ("Histories of Wilbur & Sherman").

Yount treated patients for a range of afflictions including smallpox, typhoid fever, tuberculosis, and more. Injuries such as broken bones were common, and gunplay was frequent. When Bill Stubblefield was shot twice in the abdomen by an agitated landowner while riding his horse through the Grand Coulee, a companion rushed Stubblefield to a nearby ranch, "placed him upon a table and sent a horseback rider out to Wilbur for a doctor. He made it to Wilbur in an hour and a half and returned with old Dr. Yount.

"Dr. Yount decided to operate. He opened Bill Stubblefield, placed all his intestines on the table, and washed them with a solution of strong salt water. He patched up the numerous holes in them, and after finishing this, sewed him up and packed Stubblefield in dry salt. As the doctor left he remarked that he didn't give him until morning to make it. Bill fooled him. He recovered to go through more harrowing experiences" ("History of the Grand Coulee ...," 128).

Condit was less fortunate; he died in a burst of gun violence on January 21, 1895. Condit, who had four children by two different Indian women, had fallen in love with Millie Dunn, a caretaker for Condit's disabled son, Charlie. Dunn, 40 years younger than Condit, resisted his advances and finally fled to her lover Jack Bratton's cabin north of Wilbur. When Condit tracked her down, Bratton had fled, but young ranch hand Barton Parks (or Burton Park; accounts vary) had stayed behind to protect Dunn and her 7-year-old son, James Sykes. When Dunn rebuffed Condit one last time, he opened fire, shooting her twice. She survived, but Parks and Condit both died in the shootout, killing each other simultaneously. Dr. Yount was out of town; a veterinarian ministered to Dunn's wounds and her shellshocked son.

Condit was buried in Wilbur Cemetery, while "Dunn returned to her cowardly lover Bratton and, according to the Wilbur Register newspaper, the two were charged with fornication. A jury convicted Bratton of gross lewdness and fined him $60, which Dunn is said to have paid by mortgaging several horses Condon had given her. Condon left most of his then-considerable fortune, around $15,000, to his son Charlie. The money was to go to the Wilbur school fund upon Charlie's death in March 1899, but Condon's second wife challenged the will and prevailed in the state Supreme Court. Lawyers got half the money" ("Wilbur Revels ...").

Perhaps the most notorious gunman to set foot in Wilbur was Harry Tracy (1877-1902), who stopped in the town on August 3, 1902, three days before his death. Tracy was a murderer whose six victims included a Snohomish County sheriff's deputy and a Seattle patrolman. On the run and heading east, Tracy rode into Wilbur under cover of darkness, according to a man named McGregor, "the keeper of a livery stable at Wilbur ... He says Tracy had two horses which he ordered put up for the night. He also left his rifle and bundle, asking the unsuspecting liveryman to take care of them till morning. Where he spent the night is not known, though it is said he ate at least one meal in a restaurant in the town. About 10 o'clock Saturday morning he called for his horses, bundle and rifle, paid his bill and rode away" ("Relics are in Demand"). Tracy proceeded eight miles to Creston, where he was tracked down by a posse and gravely wounded. He took cover in a wheat field, but, seeing no means of escape, "brought his revolver up under his right eye, pulled the trigger, and blew out his brains" ("Harry Tracy Dies ...").

The Hay Brothers

Marion Hay (1865-1933) moved to Wilbur in 1889. A man with political ambitions, Hay and his brother Edward (1871-1922) operated several general stores in Eastern Washington, including their flagship store in Wilbur. Hay began his political rise in 1898 when he became Wilbur's mayor. But on the evening of July 5, 1901, an oil explosion in the store's basement sparked a blaze that destroyed much of the town. The only firefighting response was a bucket brigade. Wilbur's residents escaped unscathed, but the body of an unknown man was found burned beyond recognition in a saloon. According to newspaper accounts, "It is supposed the victim was drunk and asleep" ("Charred Body Found").

The Hay brothers were soon back in business, operating in tents and shacks while a new store was being built. After it opened in 1902, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer reported that Wilbur's "greatest improvement is the rebuilding of the department store of M. E. & E. F. Hay. This new building, which is of white pressed brick, contains next to the largest amount of floor space owned by any one store in the state of Washington" ("Lincoln County – In the Great Grain-Growing District ..."). The Hay brothers sold groceries, dry goods, furniture, hardware, clothing, and, in a lot out back, John Deere tractors.

Meanwhile, they organized the Big Bend Land Company to manage their real estate, retail, and farm holdings in Eastern Washington, and Hay set his sights on higher office. "It was during his years in Wilbur that Hay began dabbling in politics on a larger scale, serving as chairman of the Lincoln County Republican Party and as an alternate to the Republican National Convention in Philadelphia in 1900. Over the ensuing years, he gained name recognition in state politics in Eastern Washington despite his lack of experience in statewide office. He moved to Spokane in 1908, and that same year ran for lieutenant governor" (Dougherty). Hay won easily as part of a Republican landslide, and when Governor Samuel Cosgrove died on March 28, 1909, Hay was sworn in as Washington's seventh governor. He sought to win the office outright in the 1912 election but lost by 622 votes, two-tenths of a percentage point, after which he returned to Spokane. From there, Hay continued to manage the Big Bend Land Company and influence the development of Wilbur and Lincoln County.

A Lively Town

Many years after witnessing the death of Wild Goose Bill, James Sykes shared his memories of growing up in Wilbur. "The roads were very rough and rocky and as crooked as a snake," Sykes told The Spokesman-Review in 1953. "The country was open prairie with few ranches, virtually no fences, with lots of sagebrush, badgers, coyotes and herds of wild horses and cattle ... Practically all the cowboys and ranchers carried sixshooters and the west was really wild and wooly when I was a boy of six years. There were several gun battles in and around Wilbur ("The Death ..."). Yet despite occasional wanton violence, the townspeople as a whole were devout, and churches were plentiful in turn-of-the-century Wilbur:

"The community boasted church representation from the Catholics, Presbyterians, Baptists, Methodists, Evangelical Lutherans, and German Lutherans. In 1888 the spiritual needs of the Catholics were taken care of in a store building. In 1900, Sacred Heart Church was built on the south hill of Wilbur. One of the most generous contributors to the building was M. E. Hay, a non-Catholic, who provided a gift of six lots and $200 in cash. The first resident priest arrived in 1906. In 1908, Sacred Heart Catholic Church undertook to drill a well on its property on the south hill. The well furnished more water than was needed by the church. After a time of disuse, the town negotiated with the church to use the well for domestic purposes. Water patrons joked that they were getting "holy water" every time they turned on their faucets" ("Histories of Wilbur & Sherman").

At least two attempts were made to incorporate Wilbur: In 1889 under territorial law, and again in 1890 after Washington became a state and the territorial incorporation was ruled invalid. A. H. Maddock became the town's first mayor after incorporation became official on August 11, 1890. Maddock presided over Wilbur's sudden growth spurt as the adjacent lands were transformed from dusty ranches into wheat fields stretching beyond the horizon in all directions. Pioneer farmers had discovered that the rolling hills contained moisture-retentive soil well-suited for grain farming. They learned further that dry-farming methods in a region with annual rainfall of about 12 inches could yield bountiful crops of wheat and barley even without irrigation.

The financial Panic of 1893 made ex-farmers out of some men, but a bumper crop in 1897 lifted Wilbur out of its brief depression and sparked a new wave of immigration and an extended period of prosperity. Some 368,000 bushels of wheat were marketed at Wilbur in the fall of 1897, "placing about $250,000 in cash into circulation" (Steele and Rose, 151). Another bumper crop followed in 1909. The 1910 U.S. Census listed Wilbur's population at 757 – though local boosters asserted a much larger number – and by 1912 the business district buzzed with activity:

"Main Street and beyond had a remarkable variety of businesses. In the west block were Bandy's Drug Store, Sherman Clay's, Wilbur Meat Company, the Wilbur Bank, and the Livery and Feed Stable. Lawyer Love had his office above Bandy's Drug Store. Beyond this block was the Madsen Hotel, with both sleeping rooms and a dining room to serve townspeople and travelers. In the east block were Gray's Newsstand and the M. E. & E. T. Hay Department Store, which took up three-quarters of the block. On the other side of the street was Bump's pool hall. The brick grocery store with the lodge hall above was at the far end of the block. Around the corner was the post office. South of Main Street was the Chinese laundry. Beyond that lay the railroad tracks on which the Northern Pacific Railroad brought mail, passengers and freight. The ice house, past the red depot, was where the engines stopped. Freight trains arrived early in the day to load wheat from the grain warehouses bordering the tracks, or to load flour from the Columbia River Milling Company" (Gaffney).

Horse Country

Horses were Wilbur's primary mode of transportation into the 1920s, and horsemanship was embedded in the culture of Lincoln County. In fact, horses outnumbered people for much of Wilbur's existence, and in the 1890s and 1900s, recalled James Sykes, "there were in the Wilbur country some of the greatest bronco riders that ever lived in the west – Tom Berry, Walt and Charlie Deer, Bill Condit, Bob Hopkins, Bill Stubblefield, the Treefy boys and many others, and the greatest time of the year was when these boys and many others like them got together for the big roundup of the stock and for branding the young cattle" ("The Death ...").

In the turn-of-the-century wheatfields, teams of horses pushed header machines and pulled wagons during the harvest. Later, "Combines were pulled by 32-horse teams. The team would have two lead horses and the driver would guide the entire team with two lines to direct the lead animals. The lead animals would guide the rest of the team" (Long). In the 1930s, 12-horse teams were still being used to plow fields. When the Seattle Post-Intelligencer toured Lincoln County in 1920, it noted that Wilbur was famous for its high standard of farm horses. Five years earlier, Wilbur horse breeder C. M. Wilson had assisted the French government in the purchase of 22 horses for use by the French light artillery in World War I.

Almighty Wheat

The wheat industry propelled Wilbur into the twentieth century, and many farmers earned fabulous sums of money; a 1967 story in the Spokesman-Review told of a newcomer from Europe who arrived at an opportune time:

"For one 1889 immigrant, Etienne Geib, there was not time to waste on any regrets and disillusionments over this godforsaken Wilbur sector, which was in direct contrast to his homeland, the tiny duchy of Luxembourg. Geib had landed at Ellis Island, headed west and, for a spell, worked in Chicago. When he landed at Wilbur, he had $16.90 in his pockets. Eventually he was to possess 6,500 acres of fine farm land and to be rated a millionaire.

"When he arrived, Geib knew no English but some of his countrymen, who had preceded him, befriended him. Geib later bought land from the Central Washington Railroad, which owned many sections of land along its right of way. He built himself a 12 by 12 foot shack and subsisted on trapped jackrabbits, potatoes and bread" (Spokesman-Review, quoted in Brumfield, 34).

Another Wilbur pioneer, "Portuguese Joe" Enoa, retired to California in 1904 after trading his farm holdings for business property in Spokane and selling more than 1,000 head of cattle. But most Wilbur wheat farmers stayed, and many farms were passed down through generations. According to a 2015 report by the Washington State Department of Agriculture, several farms had been owned and operated by the same family since the 1880s, among them Sheffels Farm and Bodeau Brothers Farm, both 8 miles northwest of Wilbur; and Bahr Ranches, 5 miles southeast of town. Together those three farms controlled more than 11,500 acres of some of Washington's most productive farmland.

Postwar Wilbur

Wilbur received an economic boost during the Great Depression when construction began on Grand Coulee Dam 21 miles northwest of town. Construction took eight years and the project employed thousands of workers, many of whom commuted from Wilbur on improved roads that had been graded and paved with crushed gravel. Wilbur's population jumped 37 percent from 1930 to 1940. But just as the dam was being completed in 1941, World War II pulled able-bodied men and women into military service. Twenty-eight soldiers from Lincoln County were killed during the war, and the postwar period began with a near-tragedy when a B-29 bomber enroute to Spokane crash-landed on Jacob Walters's farm two miles south of Wilbur. The pilots executed a wheels-up bellyflop into a wheat field, and five troops who had bailed out with parachutes were plucked from fields as far as 20 miles from the crash site. There were several injuries but no fatalities.

Another brush with death occurred in 1974 when a fog of gas swept into Wilbur following the escape of hundreds of gallons of ammonia from the nearby Cenex Plant Food Co. "Lincoln County Undersheriff Ronald John said that if a shutoff valve on a 26,000-gallon tank of the anhydrous ammonia had failed to automatically close, 'there probably wouldn't be anybody alive in the town today'" ("Town Survives ..."). No one died, but "People were lying on the ground. People were throwing up. People had passed out" ("Town Survives ...").

Wilbur weathered a lesser indignity in 1985 when the Washington State Department of Transportation put out its official state road map. Wilbur wasn't on it, prompting protests from the Wilbur City Council. "Since our town has been in the same location since 1889, this (disappearance) seems highly unlikely," the council wrote. "We heard rumors that the eastern half of Washington is often ignored by the state government, but since all the other towns surrounding us have been noted on the map, we do feel slighted" ("Wilbur Vanishes ..."). Department of Transportation officials suggested a printing problem was to blame.

Meanwhile, Wilbur was in the news for another reason: It was being touted as one of two possible Washington sites for a mammoth $6 billion federal Superconducting Super Collider project, a 30-mile-wide installation that would be buried under wheat fields east of town. Dubbed the world's greatest science experiment, the collider would be "20 times more powerful than anything now operating, in which trillions of volts of electricity would send subatomic particles flying through miles of underground tubes at 186,000 miles per second" ("Science Dilemma ..."). In making their bid, state officials pointed to the Wilbur area's stable geology, cheap hydroelectric power, and small-town life as selling points. The selection process dragged on for several years, until the U.S. Department of Energy chose a site in Texas.

Contemporary Wilbur

Wilbur was back in the news in July 2007 when national media reported on mysterious crop circles in Jim Llewellyn's wheat field just north of town. According to a Spokesman-Review columnist, "Crop circles are caused by creative, time-rich pranksters or – to the gullible souls who tumbled off the turnip truck – space aliens ... Even so, this outbreak of crop circles is a Wilbur windfall. This could prove to be – dare I say – a bigger draw than the town's annual June festival: Wild Goose Bill Days" ("Curious Crop Circles …"). More crop circles were reported in 2009, 2012, and 2013, and the tourist trade picked up. Billy Burgers, a popular Wilbur restaurant since 1955, updated its menu with an Alien Burger and Invasion Rings.

Despite the brief uptick in tourism, Wilbur is pretty quiet these days (2025). The population dipped below 900 in the 2020 U.S. Census, and the nearest freeway, Interstate 90, is an hour's drive away, leaving Wilbur well off the beaten path. "It's easy to miss this little farming town nestled between the rolling wheat fields along Highway 2," wrote one backroads wanderer after visiting Wilbur in 2021, "but it's definitely worth a stop – especially so if you are Danish. From the late 1800s to the mid 1900s Wilbur was home to 'Dane Town.' Danish last names dominate Wilbur Cemetery, just north of town: Lauritzen, Lyse, Madsen and Andersen ... In its heyday ... about a quarter of [residents] were first- or second-generation Danes" ("Finding Danish ...").

Lincoln County continues to be the No. 2 wheat-growing county in Washington, though Wilbur itself is no longer reliant on agriculture. According to 2020 U.S. Census data, 27.3 percent of Wilbur's workers were employed by local, state, or federal government, and 23.2 percent held retail jobs. Only 3.7 percent worked in agriculture, forestry, or mining. Yet Wilbur itself is far from dead: The Wilbur Register, Wilbur's record-keeper since 1889, is still published weekly. Wilbur High School also serves nearby Creston. And Billy Burgers, as famous for its neon sign as it is for its burgers, still does brisk business in the heart of town.