The Dearborn Street regrade removed a steep hill between downtown and the Rainier Valley that had been an obstacle to the development of the south end of Seattle. The hill stretched east along Dearborn Street from 8th Avenue S to just east of 13th Avenue S and extended several blocks south of Dearborn. It was washed away with high-pressure water hoses and its dirt channeled east to nearby lowlands, where it was used to raise Rainier Avenue S between Jackson and Atlantic streets. The excavation covered about 10 square blocks of private property and involved nearly three miles of streets, while another two miles of streets were filled with dirt from the regrade. The project also included the construction of a steel bridge on 12th Avenue S over Dearborn Street. It was the city's third-largest regrade project, exceeded only by the series of five Denny Hill regrades and the Jackson Street regrade. Scheduled to last 18 months, the job instead took three years, finally wrapping up in the autumn of 1912.

Small but Tall

As the twentieth century dawned, Seattle's rapidly growing population was expanding southeast into the Rainier Valley. But residents of the valley were stymied in their trips to and from the downtown core by a steep hill crossed by Dearborn Street, named after Henry H. Dearborn (1844-1909), a realtor who established the H. H. Dearborn and Company in Seattle in 1887. Later described as "one of the first men to realize the value of tide lands on the southern waterfront of the city" ("H. H. Dearborn …"), his business marketed and sold reclaimed wetlands south of downtown Seattle. He retired in 1905, and his three nephews succeeded him in managing the company. One of them, Ralph, has occasionally, but incorrectly, been credited as being the genesis for the name of Dearborn Street.

The Dearborn Street hill and its neighbor to the north, the Jackson Street hill, were part of a ridge that connected First Hill and Beacon Hill, but they were an unwelcome presence between downtown and the burgeoning Rainier Valley. Though smaller than the Jackson Street hill, the Dearborn Street hill was in places taller, rising at one point more than 110 feet above the nearby lowlands, and had an especially steep incline of 19 percent at Dearborn Street and 12th Avenue S. In addition to making for tough walking, shipping goods up the hill cost more in an era when the horse and wagon was still the primary method of local transportation. Heavy loads required more horsepower on steep inclines, which increased shipping costs, in some cases as much as five-fold. Some parts of the hill were so steep that only lighter loads could be delivered. Streetcars traveling certain parts of the hill had similar mobility issues when they were fully loaded.

Planning the Project

The success of the initial Denny Hill regrades and other, smaller regrades during the early 1900s helped motivate the City of Seattle to regrade both the Jackson and Dearborn Street hills. Perhaps because the Dearborn Street regrade was considered secondary to the Jackson Street regrade, Jackson was regraded first (between 1907 and 1910), even though the city-passed ordinances authorized both regrades within days of each other in February 1906. The first Dearborn Street regrade ordinance envisioned a more ambitious project than what eventually followed, which was due in part to conditions encountered in the Jackson Street regrade. A second ordinance reflecting these changes passed the Seattle City Council in May 1909.

The regrade covered Dearborn Street from Seattle Boulevard (now Airport Way S) to Rainier Avenue S. (The work between Seattle Boulevard and 8th Avenue S, at the foot of the hill, primarily involved grading land that had recently been filled with dirt from the Jackson Street regrade.) The regrade also covered an area south of Dearborn along 9th and 10th Avenues S that extended as far south as Norman Street along 9th, and as far south as Judkins Street along 10th. With dirt channeled from the hill, fill was added along Rainier Avenue S and just to its west from Jackson to Atlantic streets.

The project included the construction of a steel bridge on 12th Avenue S over the newly graded Dearborn Street, but during the initial planning there was some debate about whether to build a bridge or a tunnel. Residents of Beacon Hill argued that cutting away Dearborn Street at 12th Avenue S would isolate the Beacon Hill district from the rest of the city and result in unnecessary property destruction. City Engineer Reginald Thomson (1856-1949) also was initially skeptical of a bridge, stating that it was possible that within a few years Beacon Hill would be partially regraded by "twenty or more feet" ("City Councilman …") along the approach to the structure, which would require that an entirely new span be built. Along with some Beacon Hill residents, Thomson at first favored the construction of a tunnel on 12th Avenue S, but he eventually agreed with the bridge proposal.

In July, the city awarded Lewis & Wiley, the same company that handled the Jackson Street regrade, the contract for the Dearborn Street regrade at a price of $352,453.60 (equivalent to more than $12.5 million in 2025), based on a rate of 20 cents per cubic yard for dirt excavated and filled. The company's owner, William H. Lewis (1868-1923), was a well-known hydraulic engineer in Seattle who worked on a number of regrade projects in the city, including at least one of the Denny Hill regrades. In 1906 he was joined by attorney Charles Wiley (1863-1910), and the men formed a partnership that handled both the Jackson and Dearborn Street regrades, as well as a project in Portland involving the regrading of Goldsmith Hill into a series of terraces. Their partnership was cut short in 1910 when Wiley died in a drowning accident.

Work Begins

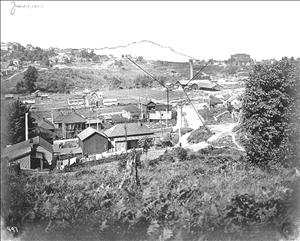

Work on the Dearborn Street regrade began on August 31, 1909. As was done in the Jackson Street regrade, the hill was washed away by high-pressure water hoses, which was possible because it was primarily compact dirt (had the hill been solid rock, the hoses would have been useless). Except on Sundays, the crews worked 24 hours a day in shifts of eight hours each. The contract called for the job to be completed within 18 months, but it took twice that long, partly due to recurring landslides and partly because of various legal battles and work stoppages. One early issue involved an injunction that prevented a significant part of the work along Dearborn Street from beginning as planned, but Lewis & Wiley was able to get around this by working on a part of the project not included in the court order. Work remained restricted to this area south of Dearborn until early 1910.

In the early phases of the project, the contractors used four hoses that pumped both fresh and salt water onto the hill to sluice it away. The hoses, called "giants" because of their enormous size, each had a 3-foot-long handle connected to a nozzle that measured between 7 and 10 feet long. The nozzle had an adjustable opening measuring between 3 and 5 inches that delivered water at a pressure of roughly 90 pounds per square inch. (The water pressure in a house typically averages 60 pounds per square inch.) The hoses were operated out of a pit staffed by a team of men, but only one man had the coveted job of handling the hose, which required a high degree of skill. The job often went to men who had experience operating similar equipment in Alaska's goldfields 10 years earlier. Other men on the team directed the flow of water and mud into a pipe where it could be funneled to the flats nearby to be used as fill.

As was the case with the Jackson Street regrade, fresh water was supplied both by the Beacon Hill reservoir and from an old pumping station on the Lake Washington shoreline at Holgate Street. Salt water came from a pumping station, located at the foot of Connecticut Street (now Royal Brougham Way) on Elliott Bay, which Lewis & Wiley had installed and used in the Jackson Street regrade. However, the company removed this pumping station in the spring of 1910 and took it to Portland for use on the Goldsmith Hill job, cutting the water supply for sluicing in half and slowing progress.

Delay After Delay

The project's pace was additionally interrupted by slides and other delays. One instance involved a dispute over an embankment. Lewis & Wiley had installed a nearly 200-foot temporary wooden bulkhead in the vicinity of Rainier Avenue S and King Street to protect nearby railroad tracks as work proceeded with filling Rainier Avenue S. But the bulkhead blocked the cars from running, and employees of the railroad tore it out. When Lewis & Wiley returned to reinstall the bulkhead, the railroad men tore out the timbers almost as fast as the contractors installed them. The railroad subsequently obtained a restraining order, forcing Lewis & Wiley off the project for a short time, until a county judge rejected a request for an injunction that would have delayed the job further.

In September 1910, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer reported that the project was 71 percent complete. There were six months remaining in the contract to complete the work, but in October, Thomson authorized Lewis & Wiley to stop work on the project until the following May. His public explanation was that it would be cheaper to resume work in the spring, when supplies would cost less and work would be easier. Thomson already had been subjected to intense public scrutiny during the city's regrade projects, and this development brought more. A storm of protest erupted, particularly from the affected property owners, who found themselves living in a place (if they could live there at all) that was a muddy construction zone and subject to landslides. "Another Case of Thomson," sneered an editorial in The Seattle Times on October 19. "He has given another example of the arbitrary power he thinks he possesses, and the property owner must suffer as a consequence" ("Another Case of Thomson").

Work continued in the spring and summer of 1911, but at a much slower pace than anticipated, and there were more stoppages. So little progress was made that by August, frustrated property owners were threatening legal action if work did not promptly resume. By this time, focus was shifting to the construction of the 12th Avenue South Bridge, which was scheduled for that year. Delays in the project had prevented sluicing operations from being completed as anticipated near the Dearborn Street cut over which the bridge would be built, but this was eventually accomplished. After the cut at 12th Avenue S and Dearborn was finished, a temporary trestle over the new gap was built for team traffic (horses and wagons), but many people refused to use it because they were afraid it would collapse.

Construction began on a permanent steel structure (one of the first steel bridges built in Seattle) in the autumn, and the new 12th Avenue South Bridge opened on January 15, 1912. The 420-foot-long bridge rises 110 feet over Dearborn Street below and has a 171-foot arch with a rise of 60 feet. There is a 94-foot cantilever span on the south end and a 96-foot cantilever span on the north end of the bridge. Because the regrade was not yet completed when the bridge opened, a temporary timber trestle was built over the deck so that its elevation would align with the roadway. In 1917, a slide destroyed the southern timber approach and shifted the bridge about 30 inches north. Six concrete approach spans replaced the original timber piles and a concrete floor was poured on the bridge in 1924, providing a 42-foot-wide roadway. A streetcar also ran on the bridge from its opening until the early 1940s. In 1974, the structure was renamed the Jose Rizal Bridge in honor of a 19th-century Filipino hero, Jose Rizal (1861-1896). Today (2025), it is the state's oldest steel-arch bridge.

Completion

Work proceeded on the regrade and fill work in 1912, and by autumn the job was wrapping up. Approximately 1.6 million yards of dirt were excavated and 1.3 million yards of dirt filled, for a total of 2.9 million cubic yards of dirt moved in the Dearborn Street regrade. It was the third-largest regrade project in Seattle's history, and it dramatically altered the land: The cut at 12th Avenue S and Dearborn Street alone measured 112 feet, while Rainier Avenue S was raised as much as 14 feet between Jackson and Atlantic streets. But the project accomplished its purpose: The grade was reduced from a high of 19 percent to a maximum of 3 percent along Dearborn Street, while the filled land along Rainier Avenue S leveled it with the newly regraded area. The Board of Public Works issued a certificate of completion for the work on October 4, 1912, though some nominal street work related to the project continued for a brief period.

The Dearborn Street regrade stayed in the news for some time afterward. The project was marred by a number of slides, including a sizeable one near 10th Avenue S and Dearborn Street in April 1910 that took several unoccupied houses down with it. Other slides received less publicity but were no less vexing. By the summer of 1913, disgruntled property owners had filed nearly half a million dollars in claims against the city (more than $16 million in 2025 dollars). Even Thomson, the regrade's biggest champion, was disappointed with the headaches and litigation that followed from the slides, later writing, "the greater portion of [the regrade's] length proved an injury to the immediately abutting property rather than a benefit" (Williams, 162). Nevertheless, there was no dispute that the city and its citizens benefited from the improvements to the land, as well as the improved connections between downtown and the Rainier Valley. Eventually, the regraded area developed into what primarily is now known as the North Beacon Hill neighborhood, though its northern and western end is considered part of the Chinatown-International District.