Carol Cornish (1886-1968), a former vaudeville singer, had a nostalgic soft spot for steam locomotives from her days riding the rails. By the mid-1950s, diesel-powered engines had rendered most steam locomotives obsolete – but Cornish had an inspired plan to turn back time. On December 2, 1956, her organizing, fundraising, and ticket-selling efforts were rewarded when the first Casey Jones Excursion – a vintage 1902 steam engine pulling 13 cars packed with 1,100 passengers – left King Street Station in Seattle on a sightseeing tour to Snoqualmie Falls. A sensation was born. Over the next 12 years, until Cornish's death in 1968, Casey Jones Excursions visited such far-flung Washington locales as Sumas, Bellingham, Ellensburg, Cle Elum, Lester, Shelton, South Bend, and Copalis Beach, thrilling tens of thousands of passengers.

Let the Old Times Roll

American nostalgia came into its own in the postwar 1940s and 1950s. In a time of jet planes, atom bombs, and tail fins, The Harvey Girls, Buttons and Bows, Gunsmoke, and The Music Man tapped a well of warmth for a bygone era. Once considered eyesores, Victorian architecture found new appreciation. And a growing coterie of railroad enthusiasts lamented the passing of the steam locomotive.

Among them was Carol Cornish. On a fall evening in 1956 she was hosting a small group of friends in her downtown Seattle apartment. They chatted about the accelerating tempo of life, the fads and fancies of the modern age, and Cornish reminisced about her youthful days as a vaudeville singer riding the rails. And now, she sighed, the wonderful smoke-belching, banshee-whistling steam locomotive was giving way to diesels. 'Well, you couldn’t stop progress. But maybe you could slow it down. Wouldn’t it be nice to ride a steam train again before they’re all gone? An old-time steam train ride through the countryside. How about Snoqualmie Falls? Splendid!' cried Miss Cornish. She picked up the phone and through friends of friends learned that the Northern Pacific Railway still operated steam locomotives in Seattle and that a train could indeed be chartered for a trip to Snoqualmie Falls. Cornish called Northern Pacific's Western passenger traffic manager F. G. Scott, secured verbal agreement, and with help from her loyal followers made the downpayment for one steam train to Snoqualmie on December 2, 1956.

But what then? Cornish was a person of modest means living on a civil-service pension; it would be great if people bought tickets, what would she do with all the money? A nonprofit corporation, friends advised. And what better name than that of the legendary locomotive engineer who notoriously sped to his death in 1900 and inspired a song? Casey Jones Excursions Inc., was born. Cornish and her friends sent flyers to fraternal clubs and had 300 tickets printed. Seattle Times columnist Byron Fish got wind of Cornish’s plans. A rail buff himself, he visited Cornish, was impressed by her pugnacity, but expressed doubt that she would be able to handle the ticket sales on her one telephone. "I was a businesswoman all my life," she retorted, "and I will have nothing to do but take ticket orders" ("Last Steam Locomotive Run ..."). Back at his desk, a bemused Fish typed up a short article touting the upcoming excursion as the "last steam locomotive run ... it will undoubtedly have a great appeal to families with young children. Many youngsters never have ridden a train before, let alone one with a steam locomotive" ("Last Steam Locomotive Run ..."). Those interested should apply to Miss Carol Cornish, "ticket agent," 907 Pine Street, or phone SEeneca 7699: $1.50 roundtrip for adults, seventy-five cents for children. The column appeared on Tuesday, November 27; the trip was scheduled for the following Sunday.

Early the following morning telephones at the Times, Northern Pacific Railroad, and Cornish’s apartment began ringing and did not stop. Cornish had just moved, and to her former landlady’s consternation, people stymied by the constant busy signals showed up at Cornish’s old apartment building looking for tickets. That day’s Times reported that hundreds of tickets had been sold. Switchboards continued swamped and a harried Northern Pacific official had to go to her apartment to sort things out. He found Cornish and a friend licking ticket envelopes. "How many have you sold?" he asked. "Oh, millions!" Cornish chirped, "we haven’t had time to count" ("Even Two Locomotives ..."). The NP man begged her to cease and desist; there were only so many coaches available and the steam engine wouldn’t be able to pull them all, anyway. Would she kindly send everyone to the railroad’s downtown ticket office where they would be put on a waiting list and the railroad would issue its own pro forma tickets. "No single casual mention of a coming event had equaled it in our experience," Byron Fish wrote ("Even Two Locomotives ...").

Passenger agents Scott, Allen Mercer, and Bob Robinson took the bit and ran with it. Workers at the King Street Station coach yard were instructed to dust off the 'last resort' fleet: a half-dozen raggedy 1910-vintage coaches kept on standby for sudden business surges. Frantic wires ordered more deadheaded west from St. Paul, the line’s eastern terminus. The railroad hated using them: They had old-fashioned red-plush 'walkover' seats, they had no air-conditioning, and they reflected badly on the image of passenger service the progressive Northern Pacific wished to project. But they were rugged, they were fully depreciated, and the windows opened. For Carol Cornish, they were perfect.

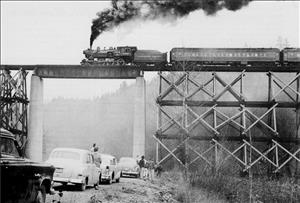

Ticket sales continued to soar and the charter price increased with the number of coaches and a second locomotive, a diesel, required to help the train upgrade. Cornish was unfazed and her affluent friends – one anonymous donor in particular – came through with the balance. On Thursday, November 29, F. G. Scott gave final approval for the special, now totaling 12 coaches and one baggage car to provide food service, to operate Seattle to Snoqualmie via Fremont, University, Bothell, Woodinville, Redmond, and Issaquah. (The train would terminate at Snoqualmie, but the locomotives would continue to North Bend and turn on the 'wye' track there.) At the engine house at Occidental and Hanford, bemused shop crews painted, polished, and fine-tuned locomotive 1372. In 1956 the steam engine was an endangered species; Seattle’s other major railroads – Great Northern, Union Pacific, and Milwaukee Road – had fully dieselized by this time, and Northern Pacific’s stable of serviceable steamers was shrinking fast under the onslaught of new diesels. Built in 1902 by the Baldwin Locomotive Works, the little 4-6-0 Ten Wheeler was recently retired from its regular freight assignments and one step away from the scrappers’ torch.

On a dour December 2, engineer Robert Still opened the throttle and the first Casey Jones Excursions special/NP Extra 1372 East puffed out of King Street Station with 13 cars filled with 1,100 ticket holders and a roughly-estimated 400 children. Left on the platform were stunned railroad officials and hundreds unable to get last-minute tickets. Onboard, it was party time – youngsters ran shrieking through the coaches, railfans sported Gay Nineties attire, accordionist Richard Tatman strolled the aisles – and cheering crowds lined the tracks. 'Cowboys and Indians' on horseback staged a train robbery at Kenmore, and at Snoqualmie town restaurants stayed open and residents offered car tours of the valley. At sundown the train arrived back at King Street Station, exhausted passengers piled off, and railroad officials shook their heads in wonderment. "It was railroading at its maddest," wrote the Seattle Post-Intelligencer’s Charles Russell, "but 1,100 exuberant passengers agreed that it was railroading at its best ... Northern Pacific Railway officials, scarcely believing what they saw, were convinced it was inspired railroading" ("1,000 Exuberant Passengers ...").

The Marvelous Miss Cornish

Carol Cornish was ecstatic. Born Edna Baker in Redwood Falls, Minnesota, in 1886, she came west with her family at age 4 and lived in Salem, Oregon; McMinnville, Oregon; and Bellingham. It was a challenging childhood; a severe spinal condition limited her activity, she was unable to finish grade school, and doctors gave her little chance of seeing 30. But her innate toughness won out; vivacious and outgoing, she drove herself through painful exercises and practiced dancing to build up strength, then put her talent to work touring Washington as a 'hoofer' with Sutton’s Merry Minstrel Maids vaudeville troupe ("I was a darn good buck-and-winger if I do say so myself!") where she fell in love with show business and trains. She went on to work as dental assistant, dance instructor, vocal coach, commercial printer, and philosophy teacher. With a growing penchant for multiple vocations and multiple personalities, she changed her name to that of a distant aunt: Carol Cornish. In 1936 she moved to Seattle and joined the Works Progress Administration as a publicity agent, then during World War II clerked for the Civil Aeronautics Administration, Army Corps of Engineers, and U.S. Navy. In 1946 Cornish’s disability forced her retirement, and on her modest civil-service pension she kept busy writing magazine articles, composing songs, painting, and as the 'Christmas Card Lady' sending used Christmas cards to hospitals and entertaining friends. Then, in 1956, she found her mark ("Carol Cornish").

As the train sighed to a stop at King Street, F. G. Scott likely sighed with relief that it was over. But for Cornish, it was just beginning. She wanted more trips to Snoqualmie, and more of locomotive 1372, which she nicknamed Old Betsy. Scott was in the hot seat; railroad management was determined to be rid of NP’s steam facilities – water tanks, coal towers, roundhouses, cinder pits – all aged and ripe for replacement or demolition, all taxable. Scott prevaricated, Cornish pressed. Disdaining bureaucratic niceties, she went straight to the top: President Robert S. Macfarlane: "Please Mr. Macfarlane, do tear loose some red tape, and smash a few barricades, butter up somebody or other and give us nice people a break. We want a steam train just awfully. Charge it up to carnival and advertising" (Cornish to Macfarlane, March 29, 1957). Cornish went on to suggest that Macfarlane, a former lawyer, offer free legal counsel to the group in its efforts to save steam locomotive 1372 and keep the trips operating over his railroad. Thus began a curious, and curiously fruitful, relationship.

Born in Minneapolis, Robert Stetson Macfarlane (1899-1982) joined a Seattle law firm in 1922, served as a superior court judge, and became a popular figure in Seattle social circles. He started at the NP in the late-1930s as western counsel and was named president in 1951. A thoroughgoing modernizer who wanted rid of steam locomotion and all the excess baggage of old-time railroading, Macfarlane now found himself in the middle of a nostalgia craze, and pen pals with a most unusual woman. Luckily, 'Mac' had been there before: In the '30s he had been a trustee of the Seattle Repertory Playhouse led by Burton and Florence James, who had raised the ire of the Seattle Establishment with their progressive plays. Florence James especially was not shy about expressing her leftist views and telling critics where to head in, as Macfarlane did his best to smooth things over. (Cornish likely would have hit it off nicely with Mrs. James – and with Burton, himself a railroad buff.)

Macfarlane said yes. Modernizer or not, he had a keen appreciation for his company’s history, paid frequent tribute to it in the company magazine, even had cars on his premier North Coast Limited decorated with historic themes. The timing was right; another few months and steam would be gone, but in 1957 the Iron Horse would have a last, glorious fling on the Northern Pacific, thanks to Robert Macfarlane and Carol Cornish. Three more trips to Snoqualmie (plus one to North Bend) ran that spring, and to save the King Street Station terminal these trips left from the 'team track' at Occidental Avenue and Connecticut Street. More multitudes climbed aboard and Cornish begged Macfarlane to save the 1372 – "This is an unorganized group, just people who love the old steam train, hate the stinking, cow-bawling diesels as far as any emotional, romantic and nostalgic yearning is concerned" (Cornish to Macfarlane, March 29, 1957). She offered to buy the engine for a dollar then lease it back to the railroad: "Your own employees now retired offer to care for the engine. They are as nostalgic as the rest of us ... They’d treat the engine like a baby" (Cornish to Macfarlane, March 29, 1957). But the diesel would not be denied, and steam bowed out in style on Casey Jones Excursions: the last run of celebrated Timken Roller Bearing locomotive 2626 to Cle Elum on August 4, and Farewell to Steam trips to Centralia on December 7 and 8, 1957.

Diesel Power and Old-Time Coaches

Cornish lamented the final victory of the "cow-bawling stinkpots" but had no intention of giving up. Steam or not, she had legions of loyal fans still willing to ride antique coaches through the backwoods of Western Washington, and new generations to introduce to old-time train travel. For the NP, Casey Jones made at best a modest profit, and though some Northern Pacific managers including President Macfarlane felt the trains did not reflect the kind of service the railroad wished to advertise, the Passenger Department prided itself on being a good host. During the first year of Casey Jones operation, department head G. W. Rodine – who had been a prime mover in making the NP’s Vista-Dome North Coast Limited one of the in-trains of the '50s – affirmed the company’s commitment: "We desire our service to be such that our Company will be considered first for any future business of this nature. All concerned please render every possible assistance to insure an enjoyable trip for all" ("We Desire Our Service"). Possibly, the words came back to haunt Rodine during the ensuing decade of fielding the requests – no, demands – of Carol Cornish, but the Northern Pacific always did Casey Jones Excursions proud.

And so they rolled, to Shelton, South Bend, Copalis Beach, Buckley, and Lester, preferably on branch lines that had not seen a passenger train in years. The first diesel trip ran to Sumas on April 26, 1958, and became an annual expedition, as did winter "snow line" trips to Cle Elum, and Labor Day runs to Ellensburg and its celebrated rodeo. Cornish made her last excursion ride in June 1960 to Bellingham, and after that her disability kept her mostly bedridden. Bent but not bowed, she continued to marshal her forces from her bedstead command post, anxiously awaiting reports from trains on the road, eagerly planning the next trips. Cornish fended off would-be copyright infringers by registering Casey Jones in every county the trains passed through. Her special priority was to accommodate disabled and disadvantaged children; profits, if any, were donated to charity, losses were absorbed by friends and benefactors. "I can’t profit by the excursions," she told the Post-Intelligencer’s Jack Jarvis, "and for the others it’s also a labor of love. We do it because we love trains and want to make it possible for others to ride them, too" ("At 78, Carol Cornish ...").

Onboard, familiar faces greeted return riders (Cornish’s mailing list ran to 4,000 names) year after year: jovial train host Tom Baker, recruited by Cornish on the 2626 trip; train manager Major Ben Keeney; and conductor Mickey Reiersgard, who loved teasing the kids sporting a Santa Claus outfit on the December trains. Tom Baker’s kids – Cathy, Elizabeth, Sheila, and Dan – ran down wayward children and hawked souvenir booklets. The train social center was the 'canteen' car, an elderly heavyweight baggage car located mid-train (though a few trips did not carry it) dispensing sandwiches, candy, ice cream, coffee, and soda. An unsung genius ordained that the large side doors be open and safety slats installed; it was the perfect sightseeing vehicle and a favorite hangout for railfans. Another top spot was the rear vestibule, a location usually off-limits on regular passenger trains. With a brakeman standing guard, folks clustered against the tailgate gazing at the track disappearing into infinity to the hypnotic tattoo of wheels on rail joints.

This author's family was among the multitudes, riding to Snoqualmie with 1372, to Sumas in 1961, and to Ellensburg in ’63, ’64, and ‘65. (The latter became a trip to Lester due to Stampede Tunnel being blocked by a freight derailment.) Casey Jones excursions were transcendental experiences taking riders out of urbane familiarity into another world: 1372’s haunting chime whistle echoing along the Raging River ... the unfolding panorama from the back platform ... fleeting vignettes of spooky trackside houses and nameless small towns ... the intriguing train-talk of the 'big kids’' ... Richard Tatman’s accordion ... the odd sense of smug superiority waving at pacing automobiles ... the good-humored joshing of the train crew ... hanging in a canteen car door watching the sun set over Stampede Pass. Many friendships began in the red plush seats, and for young riders especially, a Casey Jones Excursion was a revelation of a rural America beyond mass media and freeways.

It couldn’t last. By the mid-1960s Cornish was in failing health and so was the American passenger train. In 1967 Louis W. Menk assumed the presidency of the Northern Pacific and made no secret of wanting rid of passenger service, especially marginal operations like Casey Jones. Nonetheless, like his predecessor, Menk demonstrated a certain sentiment and ran several more trips. At last, on June 9, 1968, a train was on the road to Snoqualmie when 82-year-old Carol Cornish died at Pinehurst Sanitarium. The ancient coaches were retired to the scrap yard and Casey Jones Excursions rolled into history – a unique Seattle institution created by a remarkable woman who loved trains and loved life.