Washington’s first state parks, established in the early twentieth century, were donated by wealthy citizens who wanted to preserve natural, scenic, and historic sites. It took almost another decade for state government to launch a viable system of state parks. Washington's parks evolved in concert with national trends: conservation of natural resources, automobile tourism, the development of a national park system in the early twentieth century, the Great Depression and social programs unleashed to mitigate it, and demand for recreation following the deprivations of World War II. Political upheaval in the 1960s gave way to budget woes, which have plagued state parks since the 1970s. Washington state parks comprise one of the largest and most diverse systems in the United States, managed by professional staff and funded primarily by user fees. Challenges include adapting to climate change, accommodating diverse users, and balancing preservation and access.

The Parks Movement

In the late 1800s, urbanization and industrialization swept across the country, often leaving depleted landscapes as natural resources were harvested indiscriminately. In response, public sentiment for preserving natural places grew, with some arguing that scenery should be preserved for its inspirational and spiritual benefits while others pushed for careful use of resources to provide for future generations. Some states responded in part by setting aside land for public enjoyment. New York established Central Park in 1853 and the Niagara Falls Scenic Reservation in 1885. In the 1890s, Minnesota created Itasca State Park at the Mississippi River headwaters, Massachusetts launched a state parks commission, and Pennsylvania started preserving forests across the state. Political progressives believed preserving scenery was a legitimate and necessary use of government power to provide social benefits. At a 1908 White House conference on natural-resource conservation, President Theodore Roosevelt encouraged states to create their own parks agencies, and within a year, 41 had done so.

Developments in the Pacific Northwest echoed those occurring nationally. Mount Rainier National Park, the nation’s fourth national park, was established in 1899 in part because of its proximity to Seattle and Tacoma. President Roosevelt created Olympus National Monument in 1909 to protect the peninsula’s endemic elk and their rainforest habitat. In 1911, Oregon designated its entire seacoast a public highway, ensuring public access to recreational opportunities there. In 1913, the Washington State Legislature created the State Board of Park Commissioners to accept from wealthy citizens donations of land that would become the first state parks: Chuckanut (now Larrabee) and Jackson Courthouse.

Four-Wheel Drives

Two factors bolstered interest in a viable system of Washington state parks. In 1913, Henry Ford implemented the assembly line at his automobile plant in Highland Park, Michigan, reducing the cost of car ownership for the average American. Three years later, Congress established the National Park Service. Its first director, Stephen Mather (1967-1930), understood that people were buying cars and loved to drive them. He worked to add more parks and monuments to the more than 30 already established, connecting a strong national park system with automobile tourism.

To get to the parks, drivers needed good roads, something Washington lacked. Mount Rainier’s road to Paradise, where a new inn would open in 1917, was a nerve-wracking journey up steep switchbacks, requiring park rangers to act as traffic controllers. In 1919, Mather backpacked through the northern part of Mount Rainier National Park with members of the Rainier National Park Advisory Board, a park tourism organization. Hiking though giant evergreens, Mather told his companions that drivers wanted to motor through magnificent forests to enjoy scenic parks, and they did not want to see the devastation left by logging, the state’s most important industry. Linking roadside timber, scenic preservation, and automobile tourism was key to developing both national and state parks. Within days the group formed the Natural Parks Association (NPA), appointing one of its members, Herbert Evison (1892-1988), as secretary, and launching him on a lifelong calling.

The NPA aimed to preserve roadside timber and implement a robust state parks system, both of which would increase tourism opportunities. Filling its board with prominent citizens, including former Seattle mayor and industrialist Robert Moran (1857-1943), the NPA convinced the 1919 state legislature to give the state lands commissioner, a member of the State Park Board, permission to set aside five-acre tracts next to public highways for parks, connecting roadside timber, scenery, and auto tourism as Mather urged. Mather knew that people needed different types of parks, but he wanted only superbly scenic, nationally unique places to be national parks. He recommended the development of "comfortable camps" everywhere, so that travelers "could camp each night in a good scenic spot, preferably a state park" (Tilden, 8). But Washington was one of only 12 states with more than one state park. Twenty-nine states had none; seven had only one. In January 1921 Mather convened the National Conference on Parks in Des Moines, Iowa. Two hundred delegates from 25 states attended, including Evison.

Rapid Expansion

When Evison returned, he and the NPA convinced the legislature to rename the parks board the State Parks Committee and expand its powers. In addition to administering all parks and parkways and planting trees along public highways, the committee could also acquire new parks, provide camping, and grant concessions to raise revenues. The Commissioner of Public Lands, a member of the State Parks Committee, was empowered to withhold state lands for park purposes so long as it did not create a revenue loss for schools, the main beneficiary of state forest lands.

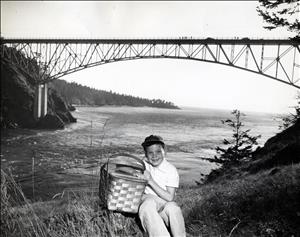

Within this framework, the system quickly expanded. From the initial 20-odd acres in 1913, state parks holdings numbered more than 5,500 acres by September 1922. Washington state parks now included about 3,000 acres on Orcas Island donated by Moran, an 1,800-acre former military installation at Deception Pass transferred from Congress, a singular limestone cave a quarter-mile from the Canadian border in the state’s far northeastern corner, and several smaller sites. Commissioner of Public Lands Clark Savidge reserved 520 acres of ancient trees along the Pacific Highway in Lewis County so automobile tourists could appreciate the state’s most important natural resource in Lewis and Clark State Park.

Just as Washington state parks were gaining momentum, political changes stalled progress. After his inauguration in early 1925, Governor Roland Hartley (1864-1952) vetoed a $50,000 appropriation for state parks and killed a bill that would have given the State Parks Committee the power to condemn lands it wanted to add to the system. State parks funding was only $12,900 for the biennium. Supporters despaired, the Natural Parks Association withered, and Herbert Evison went to work for Seattle photographer Asahel Curtis at the Rainier National Park Advisory Board. Park supporters throughout the state bided their time while Hartley was in office.

Re-elected in 1928, Hartley vetoed all appropriations for state parks, labeling them "nick-naks" (Cox, 71). Parks were "set aside for natural beauty and to preserve places 'untouched by civilization and the greed of man,'" he said, not as "amusement parks and tourist camps" (A History ...). Starved of funds, the State Parks Committee began shuttering parks. Evison left Washington to accept a position as secretary of the National Conference on State Parks.

The CCC Creates the Modern State Park

The country was in the depths of the Great Depression when Washington elected Clarence Martin (1886-1955) as governor in 1932. Jobs, food, and shelter were policy priorities, not parks. Congress enacted the Emergency Conservation Work (ECW) Act, a main component of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, in March 1933. The legislation created the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), a jobs program that employed young men to perform needed conservation work across the country. Enrollees, mostly between 17 and 23 years old, enlisted for six-month terms renewable for up to two years and received clothing, housing, medical care, food, and education. Of their $30 monthly salary, $25 was sent home to help their families. Working outdoors and eating good food helped most recruits gain weight and strength after years of Depression deprivation.

The National Park Service managed CCC work in state parks and hired Herbert Evison as deputy for CCC oversight, placing the longtime state parks champion in a powerful position. By July 1933, nearly half of the 245 established CCC camps were in state parks. Two years later, the number of camps had nearly doubled.

CCC infrastructure, must of it in the rustic style known as "parkitecture," comprises some of the most cherished features of Washington parks. Designed to blend into the local landscape, CCC handiwork used local supplies and materials when possible, and local experts taught construction skills. In Washington state parks, the CCC built roads, campgrounds, picnic areas, trails, comfort stations, railings, water tanks, caretaker housing, and fences. Taken by train to an empty stretch of shoreline on Puget Sound, the CCC built Saltwater State Park from scratch. The viewing tower atop Mount Constitution in Moran State Park; the kitchen shelters and bathhouses at Millersylvania, Twanoh, and Rainbow Falls state parks; structures at Deception Pass; the original swinging suspension bridge at Riverside; and Beacon Rock’s campground and group shelters are all examples of CCC work. Other parks, including Kitsap Memorial and Sacajawea, feature projects completed by the Works Progress Administration (WPA), another federal jobs program. From 1933 to 1941, Washington state parks enjoyed federal investments of a million dollars a year.

Although the CCC is justly lauded for its work, Black enrollees experienced discrimination and segregation, including in Washington. State Parks director William Weigle and the State Parks Committee expressed dismay about Black enrollees working at Millersylvania and Rainbow Falls. Black CCCers at Millersylvania were assigned kitchen work, depriving them of the chance to learn construction skills, and were required to use separate bathing beaches on the park’s Deep Lake. The State Parks Committee wrote Congress requesting that Black enrollees be segregated from other CCC workers and from park visitors. Bowing to bigotry, the national head of the CCC implemented a policy requiring Black enrollees to work only in their home states. Washington’s Black CCC enrollees were reassigned out of the state in 1934.

The massive infrastructure built by the CCC, WPA, and other works programs was the "go-ahead signal for the development of state parks in the United States" (Wirth, Ch. 4b). National events transformed Washington state parks and, thanks to the funding and staffing on offer, built the groundwork for today’s modern state park system. The acreage available for recreation and scenic enjoyment expanded. States learned from each other, and standards for state park management became more unified.

And from 1933 onward, state parks were closely connected to national policy. As the federal government’s principal liaison with state parks, the National Park Service provided expertise and assistance. The Washington State Planning Council participated in a 1936 national survey of recreational lands. In the resulting 1939 study, it recommended changing the State Parks Committee to a seven-member, governor-appointed citizen board, hiring a full-time director of state parks, inventorying state lands for possible park sites, providing more boating parks and facilities, and adequately funding parks.

Beyond World War II

Washington’s population increased by more than one-third during the 1940s as well-paying wartime jobs attracted newcomers who appreciated the state’s scenery and recreation. Despite lower park attendance during the war, by war’s end the State Parks Committee estimated that Washington’s parks needed more than $4 million in backlog maintenance. Recognizing that a much larger population meant more demand for and impact on state parks, the state legislature funded a 1945 statewide survey of recreational and cultural resources. In 1947 the legislature reimagined the State Parks Committee as the Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission (WSPRC), to be composed of three elected state officials and four governor-appointed citizens, giving it authority to hire both a state parks director and a supervisor of recreation, and ordering it to work with state and federal agencies. In 1949 State Parks created a Recreation Division to help communities create recreation programs. The postwar demand for recreation helped professionalize state parks management.

Recognizing the increased pressures on parks, in 1949 the state legislature dedicated $1.20 of every $3 vehicle operator’s license fee to state parks. It further ordered State Parks to create more boating facilities on Puget Sound to meet rising demand for water recreation. Governor Arthur B. Langlie (1900-1966) contributed $12,000 from his emergency fund and the legislature appropriated about $25,000 in the 1953-1954 biennium. One in 10 Puget Sound area families owned a boat in 1950, a number that surged to one in four by 1960, by which year State Parks had built marine facilities at 14 areas. For those who preferred water in frozen form, State Parks added winter sports facilities at Fields Spring, Mount Pilchuck, Brooks Memorial, and Squilchuck state parks.

In 1948, Congress authorized using surplus government property, including decommissioned military sites, as parks. A number of former coastal defense sites on the Pacific Coast and Puget Sound were attractively located. To inform its management of these important places, State Parks created the Advisory Board on Historic Sites in 1949 and hired its first full-time historian, Albert Culverwell, in 1953. The agency added Fort Columbia, Fort Townsend, Fort Casey, Fort Flagler, Fort Worden, Fort Simcoe, and Fort Canby (now Cape Disappointment) to the system during the 1950s, and Fort Ebey in the 1960s.

By 1950, the state’s 52,290 acres of parks received 1.64 million visits each year. A 1956 State Parks report noted dryly, "The people in a nation that uses 15 tons of aspirin daily can be expected to need and use parks to a maximum degree" (DeTurk, 3). More parks were urgently needed: "The rate of increase in attendance in Washington State Parks, and the increase of campers within that attendance far outstrip the available park development at the present time ... [and appropriations] do not nearly keep up with fixed costs" (DeTurk, 27-28). In 1957, the state legislature raised the driver-license fee again, this time to $4, and sent $2.20 of every fee collected to State Parks. Parks desperately needed the money. By 1960, annual visitation was more than 7 million, more than quadruple what it had been a decade earlier.

Political Upheaval

As Washington officials and State Parks scrambled to create more parks, more facilities, and more revenue to fund it all, the federal government continued to address recreation demand at the national level. In 1958, Congress established the Outdoor Recreation Resources Review Commission (ORRRC) to determine future demand for outdoor recreation and recommend policies. Its 1962 report, Outdoor Recreation for America, suggested states pass bond issues and charge user fees to raise general recreation funds, and contract with private concessionaires to provide some services such as boat rentals or snack bars. It urged a federal grant program to help states grow their recreation lands and facilities, resulting in 1964’s Land and Water Conservation Fund, funded by proceeds from federal leases for offshore oil and gas.

Washington responded quickly to the ORRRC report. Governor Albert Rosellini (1910-2011) appointed an Interagency Committee on Outdoor Recreation (IACOR) in April 1962, charging it with studying current recreation opportunities, the economic benefits of outdoor recreation, and making recommendations. The IACOR’s April 1963 report laid out plans for increasing marine recreation, implementing youth camps, and expanding the state parks system.

In November 1964, Washington voters passed two measures to fund state parks. Initiative 215 authorized the use of unclaimed marine fuel tax refunds to purchase or improve marine recreation land and made the IACOR permanent. Boosters of the initiative were especially concerned by the shrinking amount of waterfront land available for recreation as more transferred to private ownership. Referendum 11 authorized the issuance of outdoor recreation bonds to be administered by the IACOR as grants for local governments and organizations. Both passed overwhelmingly; Washingtonians wanted more recreation options and were willing to pay for them. Revenues raised allowed Washington State Parks to expand the park system by adding nine new marine parks, mostly in the San Juan Islands, in the 1960s.

Even as the system grew, upheaval and high staff turnover inside the agency threatened to slow progress and undermine its reputation. This was largely the result of Rosellini’s attempts to politicize appointments to the WSPRC and insert political allies in senior staff positions. In 1963, the commission appointed Charles H. Odegaard, the 35-year-old regional director of the National Recreation Association, as state parks director. Odegaard brought much-needed stability to the agency during his 16-year tenure.

In 1969, partly to isolate state parks from political influence, the state legislature adjusted the WSPRC to its current model of an independent commission with seven governor-appointed citizens who provide policy advice and guidance. At decade’s end, Washington State Parks was a fully professionalized agency, a transition affirmed when Odegaard received the National Conference on State Parks’ National Award for Excellence in 1972.

Money Woes

Inflation and state budget cuts in the 1970s significantly impacted Washington's state parks. In early 1971 State Parks closed five parks for several months and put another 34 on restricted schedules. Although the affected parks reopened within months, the closure was predictive. State Parks had to figure out other ways to bring in revenue. The nonprofit Washington State Parks Foundation formed in 1972 to raise private money. Demand for parks continued to rise, though not as dramatically as the previous two decades, and the agency warned, "in both volume and variety parks usage has outstripped facilities development" ("1971 Annual Report," 39). These challenges were exacerbated by the fragmentation of recreation pursuits into narrow specialties, such as snowmobiling, motorbiking, and scuba diving, each with small but vocal constituencies. Pleasure boating continued to grow, as did winter park use, which more than doubled between 1962 and 1972.

By its 75th anniversary in 1988, Washington had 88 state parks that received more than 40 million visits each year. But strains on the system were more evident every year, as the agency now had "the problem of providing enough land for both the users who want to participate in active recreation and for those who wish to passively enjoy the natural environment. Although the number of state parks is large, many are small in size" (A History ...). Preserving and protecting land and natural resources had to be balanced with providing public access and diverse yet appropriate forms of recreation. But insufficient funding and unpredictable state and federal government support made that more difficult.

The 1990s were a "constant struggle for survival" for Washington state parks (Landrum, 202). Funding from the federal Land and Water Conservation Fund was inconsistent, so the state could not rely on grants for land acquisition or facility development. The state legislature did not always view state parks as a basic service of government. In 1998, facing severe budget cuts, Washington State Parks identified 21 parks for closure that would save $3 million, and another 16 that if closed would up the savings to $5 million. Public outcry was immediate and loud. Users felt state parks were "as essential as any other public service, and they must be pursued just as aggressively and vigorously as the rest, with an equal claim to legitimacy" (Landrum, 202). Friends groups and volunteers became increasingly important to park operations and maintenance. Finally, concerns about ranger safety, especially in more remote parks, inspired the commission to approve transitioning park rangers to law-enforcement officials, which meant they would be trained at the State Patrol Academy and carry weapons.

The first decades of the twenty-first century were even more difficult. State parks were often on the chopping block as state governments looked for places to cut budgets. In 2002, to save money, Washington State Parks returned four leased parks to federal and public utility landowners. The Washington State Parks Foundation, which had all but disappeared in the 1980s, was resurrected to help raise money and awareness for state parks. The state legislature approved a first-ever $5 parking fee in 2003, although negative public response resulted in its abolition in 2006.

The 2008 recession forced even more drastic and difficult transformations in Washington State Parks. Faced with a billion-dollar revenue shortfall, the Washington State Legislature made budget cuts to State Parks, which cut staff, reduced park hours, and consolidated operations. By the 2009-2011 biennium, State Parks planned for a 23 percent budget cut that would close or mothball 40 parks. Although most parks were saved after protests, five parks were offloaded to local governments or other entities, and parks supporters were "left playing a losing game of closure-list Whack-a-Mole" ("Closing State Parks ..."). Between 2008 and 2012, one-third of agency staff positions were downgraded from full-time to seasonal. State general fund money for operations, which had made up 65 to 80 percent of the agency’s budget until 2009, was reduced to 30 percent, then to 12. By 2013, its centennial year, State Parks was expected to find nearly 90 percent of the funding needed to operate its 117 parks. Within five years, one of the nation’s largest state park systems had gone from a prized asset to an almost-independent organization reeling from financial shock.

Part of the solution was the Discover Pass, a more successful attempt at imposing user fees for state parks. Implemented in 2011, the pass costs $30 a year for parking on most state recreation lands, including those managed by the state Department of Fish and Wildlife and the Department of Natural Resources. State Parks receives 84 percent of the revenue generated by the Discover Pass (the other agencies each receive eight percent). Today, earned revenues provide 64 percent of the agency’s budget. Of that, 37 percent is from Discover Pass sales, 40 percent from overnight accommodations (camping, yurts, cabins, and vacation houses), and 23 percent from donations through the state’s vehicle licensing program, the Washington State Parks Foundation, and other sources. Only a third of the agency’s budget comes from the state general fund.

Challenges and Opportunities

Depending on how one counts, Washington has 124 state parks [in 2025], including traditional state parks, historical state parks, marine state parks, and state park trails. There are also 16 state park heritage sites, smaller sites that can be part of larger parks, such as the Lake Lenore Caves within Sun Lakes-Dry Falls State Park, or standalone sites such as Steptoe Battlefield. It’s one of the largest and most diverse state parks systems in the United States. With the exception of large swaths of federal land, mostly national forests and parks, no matter where you live in Washington, there is a state park nearby. They are staffed by about 1,100 employees, just over half of whom are either full- or part-time seasonal workers.

Washington State Parks faces multiple challenges including funding, maintenance, climate change, diversity, and competing uses. Inconsistent and unpredictable funding makes it difficult to plan long-term.

One result of decades of erratic funding is a parks maintenance backlog of about $500 million. The agency owns about 2,800 buildings, mostly in parks, or about one-quarter of all state-owned buildings. The parks are essentially small cities, with a public works system that includes roads, boating facilities, sewer and septic systems, electrical works, and housing, all of which require maintenance and updating. Half of the backlog involves more than 800 historic structures (more than owned by any other agency).

Addressing climate change means that some parks and park ecosystems will require adaptive strategies. Seasonal visitation is likely to increase as temperatures rise, increasing operational costs. The agency’s climate and sustainability program implements strategies to mitigate climate effects, including reducing carbon footprint through cleaner transportation, including electric vehicles and machines, and energy efficiency efforts such as solar panels.

Making parks welcoming to all people is a major emphasis. State Parks programs offer events and gatherings for diverse groups of users, many of whom have not been typically represented in the parks. The Folk & Traditional Arts program brings musicians, storytellers, and artisans to parks to share their cultural traditions. On a summer Saturday, a local park might host a Laotian festival, a poetry slam, a Japanese calligraphy workshop, or embroidery exhibit.

Tribal partnerships acknowledge that all Washington state parks occupy Native homelands and seek to foreground indigenous knowledge and perspectives. Washington State Parks created a Tribal Relations Director position in 2023. With several other state agencies, State Parks is part of the State-Tribal Recreation Impacts Initiative, which seeks to improve cooperation and recognize shared interests and opportunities around recreational resources. Kukutali Preserve, established in 2010, is co-managed by the Swinomish Tribe and State Parks. The newest state park, Nisqually, is a joint effort of the Nisqually Tribe and Washington State Parks to protect a culturally and historically significant area where the Nisqually River connects Mashel Prairie and the Puget Sound lowlands to the foothills of the Cascades near Mount Rainier.

Finally, State Parks continues to work to balance competing uses. State parks are both resource banks and recreational spaces, and as the number of state parks users has grown and recreation has specialized – considering, for example, the environmental impact of recreational vehicles, snowmobiles, and jetskis relative to that of tents, Nordic skis, and kayaks – maintaining that balance is increasingly difficult. State Parks launched a Scenic Bikeways program in 2020, and oversees motorized and non-motorized winter recreation in Sno-Parks on private, state, and national forest land. Its Recreational Boating Safety Program, funded with federal grants through the U.S. Coast Guard, provides boater education and certification, a life jacket loaner program, boat pumpouts, and more. In addition to law enforcement, administration, maintenance, and communicating with the public, rangers lead hikes, offer interpretive programs, conduct stewardship, and supervise events.

The 138,500 acres in Washington's state parks received more than 40 million visits in 2024, which translates to more than five park visits per year for each resident. According to a 2015 report, state parks are "an engine for rural economies and redistribute ... wealth to rural regions by attracting significant spending from non-local participants" ("Economic Analysis," 39). Washington’s parks generate $1.5 billion in consumer spending and contribute $1.4 billion to the state’s economy, creating jobs and state and local tax revenue. They provide "critical outdoor recreation assets" while enticing out-of-state visitors, who spend money in Washington ("Economic Analysis," 39). The most popular parks, like Deception Pass and Lake Sammamish, each attract more than 2 million visits a year. Higher visitation, prompted in part by people seeking outdoor spaces during the COVID-19 pandemic, may have helped create a new cohort of state park supporters. A major challenge for Washington State Parks is how to accommodate more visitors in relatively small spaces while protecting important natural and cultural features, amid chronic economic unpredictability.