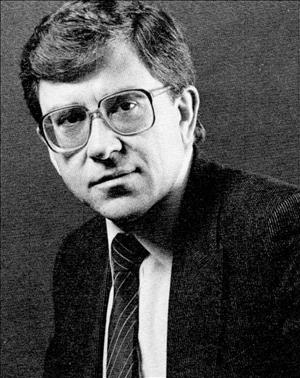

Brian Boyle has worked as a mettallurgic engineer, miner, county commissioner, university professor, environmental consultant, and for 12 years (1981-1993) was the Commissioner of Public Lands of Washington State. In this March 2025 interview with HistoryLink's Jill Freidberg, Boyle talks about his work in metals and mining, how he made political inroads as a Cowlitz County commissioner, his innovations and various disagreements with the timber industry during his stint as Commissioner of Public Lands, why he started the Northwest Environmental Forum at the University of Washington, and his role in co-founding the Mountains to Sound Greenway.

Born in Butte

Brian Boyle was born in Butte, Montana and attended the Montana School of Mines in his hometown. Trained as a mettalurgical engineer, he's had a lifelong love affair with the great outdoors.

Brian Boyle: Well, I grew up in Montana, so you can't not have some relationship to forests. I used to go hitchhiking to go fishing. There's a place called Brown’s Gulch, which is just about 6 miles west of Butte, and we used to take our bicycles, my friend and I would go bicycling out to Brown’s Gulch to catch fish underneath beaver dams. But so if you were going to the forest, you were actually going with a purpose, and it wasn't just to hike around.

My town was Butte. Among other things, my parents never had a car in all their lives. My mother was quite a businesswoman, and I grew up kind of as a little kid on my own in a lot of ways, because she started a business, a toy store. And my dad worked full-time, or more, and she ran this toy store, and I was working there. My dad was a timekeeper in the mine, and in those days they didn't have clocks, and you had a timekeeper to check the names of people, or checked in and checked out to make sure that they actually lived at the end of the day.

I got a degree in what is now Montana Technological University, which at the time was Montana School of Mines. And my undergraduate degree is metallurgical engineering. I worked my way through the School of Mines by working in the mine. I became a miner, underground. I worked for five years underground as a miner. Worked Friday and Saturday nights during the school year, and worked all the holidays and Christmas, and vacation, and summers underground. It was hard work, extremely hard work. You learned to use a shovel and a pick, and you also learned to handle dynamite and put timber up and stuff like that. I talk to people and they say, "What? You worked in the mine?" I’d say, "Yeah.” They can't understand it.

Moving to Longview

BB: Well, I was offered a couple of jobs coming out of college, and one of them was in Tucson, and one of them was in Whiting, Indiana, right in the Gary, Chicago area. So, I went to work for a company called Federated Metals, part of American Smelting and Refining. Hired me as a metallurgical engineer. We basically reclaimed scrap and made brass and bronze but also made a lot of alloys that were very sophisticated alloys used in strategic material for warfare. Nextdoor to where I worked, there was U.S. Steel and Inland Steel and American Oil belching out all this junk; you’d come out to your car at the end of the day and the car was all covered in red dust from the blast furnaces, and really, a really messy environment.

I could have stayed there, but I started looking around. I contacted Reynolds Metals about their plants in Longview and in Troutdale, and I just wrote them a letter. I said I was interested in working in one of those places. The guy called me from Chicago and asked if I'd come and see him, and he talked with me and they gave me a written test, and about a week later, they called me and asked if I'd come to Longview to meet with the manager. I met with the top managers and they offered me a job on the spot as a metallurgical engineer. They were expanding the Longview plant, tripling the size of the plant in about three years, and so I was working with that.

Got off the plane in Portland, I think it was in May, and rolled down the windows of the rental car and drove north and the beautiful weather, and I thought, "Man, this is so much nicer than Chicago."

But it was a highly efficient plant. The part that I was in charge of, which was the casting operation, we were producing over a million pounds of metal a day out the door.

County Commissioner

Boyle satisfied his political ambitions when he ran for Cowlitz County commissioner and won. But before long, he found himself and the county at odds with timber industry giant Weyerhaeuser.

BB: Longview was a big center, that area, Cowlitz County, was a big center of timber. So the people that were running the show there, particularly Weyerhaeuser, [are important people], such as Dick Wallenberg, the owner of Longview Fibre. I knew some people in the timber industry, you muck around with people and you meet them at meetings and things.

I was thinking about running for office, running for county commissioner, because the guy that had been in office for 20 years decided to retire. I got into it and there were a whole bunch of people in the election, eight or nine people. Because I came from industry, industry people supported me. I had a lot of friends that came out and really, really worked doorbells for me and stuff like that, worked really hard. And I got elected. Then I sort of turned Cowlitz County upside down, got involved in a lot of the social issues, mental health, and drug-abuse issues and things like that. I started the first juvenile-diversion program. I think it might have been the first juvenile-diversion program in the state.

And then the state was enacting a Shorelines Management Program. I decided that we were not going to enact the Shorelines Management Plan for Cowlitz County until we enacted a comprehensive plan for the whole county. The Shorelines Plan had to fit into it.

But then you bring in the timber industry. They didn't like our Shorelines Plan because we told them how close they could log and that they had to keep their equipment out of the streams and all this kind of stuff. We got after them and brought some lawsuits against Weyerhaeuser. That was where my reputation with the timber industry started. They really decided early on they didn't like me.

Running for Lands Commissioner

By 1980, Bert Cole, Washington's Commissioner of Public Lands for 24 years, had become increasingly unpopular. Cole was seen as being vulnerable in the November election, and 10 candidates, including Boyle, lined up against him, though only Cole, Boyle, and plywood factory executive Larry Malloy were considered serious contenders. Washington's lands commissioner manages state-owned lands through the Department of Natural Resources (DNR).

BB: There was a lot of timber in Cowlitz County. And so the DNR would come in and they would give us kind of an annual report about what timber was going to be cut in Cowlitz County for the year. And so I got to know a couple of DNR people. And I was having lunch with a guy, county commissioner in Clark County, Dick Granger. And he ran a small sawmill out in Eastern Oregon. And I knew he was thinking about running for lands commissioner. So Granger and I had lunch and I said, "I hope you're going to run for Lands Commissioner." He said, "I don't think so. I can't afford it. I need to run the mill. I don't have anybody to do it. I can't do it."

Later that day he called me and he said, "Let's have dinner." So we went out and had dinner together and we drank a bunch of wine. And he said, "I think you should make a go at it.” And I said, "I can't do that." So I started calling people around the state that I knew, county commissioners that I knew. And I'd been involved in the statewide task force that Daniel Evans had appointed, about 1973 and '74, called Alternatives for Washington. And I started calling those people. I said, "What do you think about this?" "Oh, you don't have a chance. It's too late. You should have done it six months ago." This was in June. So I thought, "Well, that's it."

And the next day people started calling me back. "You don't have a prayer but I'll support you." And then I got a couple of calls from people in the timber industry. One guy was a prominent lobbyist. He's a guy named Gary O'Reilly. He said, "There are people in the industry that'll help."

So I went up to Olympia. It was like 10 minutes to 5 and I filed. And it was six weeks before the primary. And I put together a campaign committee. You remember Jolene Unsoeld? Congress in the third district, a Democrat. She was on my finance committee because she was an old friend. So she came to my finance committee meeting in Olympia and we put together the whole plan about how we'd run this campaign in basically a couple of hours. [Cole] outspent me seven to one. I had nothing. But I started going around the state, and I started with Ted Natt at the Longview Daily News. And he endorsed me right on the spot. Went down to Vancouver, to the Columbian, and they endorsed me on the spot. And then I went to the P-I and the Times, and they call each other, these editors. So they call Ted Natt, "What do you think of Brian Boyle?" So I get the P-I and the Times to endorse me. It was before the internet. So the newspapers had some sway!

I won by 20,000 votes out of 1.8 million cast. And of course, I won all the east side [of the state] because people in the rural areas really wanted the DNR to change. And so here I am a Republican and I was endorsed by every environmental organization in the state, all the big environmental organizations, because they wanted him out.

Landing the Job

BB: The lands owned by the state are held in trust, in the constitution of the state. They're held in trust for the people of the state of Washington, the common schools, and the universities. They're all named in the constitution. And so the job is to manage the trust and to not mess it up. That includes the forests and includes a lot of agricultural land and a lot of land that is used for grazing and other things. DNR is the largest marketer of wheat in the state of Washington. Probably it may be the biggest tree-fruit producer. Apples, pears, apricots, all this kind of stuff on lands in the eastern state. In 1989, the centennial year, I invited the long-term lessees of state lands to come and meet and just get together. It was in Yakima or Ellensburg. And there were people that had been, in their families, had been leasing state lands since statehood!

The forester would argue that you have to log something, then you replant it, and then 40, 50, 60 years from now, it's going to produce more money for the Trust, and that land is supposed to be managed for all the people. But I would argue that "all the people" means many generations from now. So anyway, that's the land commissioner's job, in addition to chairing a whole bunch of boards and commissions like the Forest Practices Board and stuff like that, where you basically regulate the timber industry.

Formulating and Executing a Plan

Boyle took office in January 1981 and served as lands commissioner until January 1993.

BB: When I first took office, there were something like 200 lawsuits against the DNR. There were a couple of big ones brought by environmental organizations. I wanted to get DNR out from under these things. So what I did when I came in office was, I said, "There's no plan. There's nothing that says what it is we want to accomplish, with this trust, over time ... As we write the plan, we're going to then look at the environmental impacts of that plan," I said. "I want everybody in here, planners, foresters, scientists, forest ecologists, typists, everybody in here." There was one state attorney, Nick Handy. He and I and a couple of other attorneys sat down and talked about this. We laid out a set of criteria for them. I said, "You're going to do a plan. Here are the elements of the plan." There were 18 elements. "Every one of these has to be addressed." Anyway, we did this and we developed this plan. It was a 10-year plan for forest management. We called it the Forest Land Management Plan for DNR. The lawsuits were dropped.

Boyle also had to deal with a dysfunctional economy. Democratic President Jimmy Carter had just been defeated at the polls, swept aside by Ronald Reagan.

BB: Jimmy Carter went out of office with interest rates up 16, 17 percent, even 21 percent in some cases. The economy was just in shambles. The timber industry, they had been bidding timber prices up just sky high. So you’d buy a timber sale and maybe it's a $5 million timber sale, which is not unreasonable; $10 million timber sale, could be. DNR had rules. You had to put 10 percent down cash. So you’d have to fork over $500,000 or a million dollars on a $10 million sale.

So then the timber industry started defaulting on their timber sales, which was illegal. So it went to the legislature and the legislature wanted to pass a bill to bail them out, give them back all their deposits and let them give back their timber sales, which they were under contract to buy. And I opposed it. And I had a number of people tell me, "Brian, you really have to be careful here." I did testify against it. I said, "I think it's unconstitutional." But they passed the bill. They gave them the bailout.

The state school board jumped in and sued. They filed the case in Clark County of all places. The judge in Clark County ruled that it was unconstitutional and that the legislature had acted in violation of its public trust. He took it, with appeal, to the state supreme court, and the court ruled 9-0 in favor of the lower-court decision. So what am I going to do? You know, all these people, it wasn't just the big timber industry. There were people like some logger out in Forks that bought a timber sale. He's a two-person business. His wife answers the phone and drives the truck and stuff like that. There really were a bunch of people like that. And small sawmills up in, you know, Sedro-Woolley.

So I called together a meeting of all the timber industry. And I said, "Look, here's what we're going to do. We're suing you today." I talked to Ken Eikenberry, the attorney general. We agreed on this whole thing. At the same time I was talking to the industry and telling them, "We are suing you. It's happening today," the Attorney General had people in various courthouses suing. So it all happened in the course of an hour. And they were flabbergasted. They had no idea what we were going to do. And I said, "I'm going to appoint a committee and we're going to take a look at this. And we're going to come back at you. We're going to give you an opportunity to settle this."

And then we got the word out to people. Who's going to be first? Who's going to set the pattern of settling with us? They started just kind of dribbling in. And finally we got them all. The last one was Weyerhaeuser. Our group came in and they said, "We’ve got a settlement with Weyerhaeuser." I said, "It's not enough. I won't take it. They have held us up. They've held everybody else up and I will not take it. We want 80 percent." So it took four years. We worked it out with people. I mean, sometimes they had very few assets. You can't take their sawmill. You can't take their only truck they own or whatever type of thing. And so there were different standards for different people. We just had to work it out.

Timber Fish Wildlife and Northwest Environmental Forum

BB: With DNR, we started looking at our timber sales and realizing that we needed to do something different about clearcutting. Of course, this was in the forest plan that we were supposed to do this. Some of the forest industry didn't like the idea that we might do smaller clearcuts or have intervening areas between clearcuts, leave trees, standing trees, and snags and things like this. Of course, the tribes, they wanted streams to be protected and they were after the timber industry.

Stu Bledsoe, who was the head of the Washington Forest Protection Association, and Billy Frank Jr. then got together, and they got a meeting with me and said, "Why don't we start something, and we'll help name the people that need to be at these discussions, but you cause it to happen.” So we had these meetings, typically up on Snoqualmie Ridge, where we’d have these discussions and try and set some standards for the different practices on forest land. Part of that got me thinking about, after I leave office, what do I want to do in terms of trying to get people to start talking, start understanding what it is they really think about things, as opposed to having them in a contentious, adversarial situation where the only time they see each other is when there's something on the table that one has to be opposed to and one has to be in favor of. Northwest Environmental Forum was what I came up with.

We got the Forest Service there. The Forest Service typically didn't go to these kinds of things with the normal people who were wrangling about the Forest Practices Act and stuff like that. But they were there, and the forest products industry, and some tribal leaders, Tulalip and Nisqually in particular. I was always disappointed because a lot of environmentalists just wouldn't do it. They just didn't want to be part of it. And some did. I really appreciated them. Some of the most difficult came because they weren't afraid of it.

But then when the Forest Service put together their Northwest Forest Plan, they left people out. They wouldn't allow people to go there that were not part of their kind of blessed group. I think it was a total failure, a total failure, and it basically just eviscerated whole parts of the Pacific Northwest economy.

Tales of Trails

BB: Harvey Manning, who has written a number of books, I met Harvey when he came to a fundraiser for me when I was running. He didn't give me any money, but he came. And he said, "You know, after you get elected, I wish you'd come out and we could go on a tour together." So we agreed to do that. And it was probably '82 or '83 or something like that. Got into Harvey's VW and we drove all around. I always joke about it, it smelled like dog, like wet dog. But I joke about that, tell people that about Harvey's VW. And they all knew it because they had all been in that VW.

Tiger Mountain is the base of the Mountains to Sound Greenway. And Tiger Mountain was jointly owned by DNR and Weyerhaeuser. So we drove around there and we went out to a bar in North Bend and had some drinks and talked about it. And what was happening was that there'd be a small timber sale on Tiger Mountain. And it's not that big of an area. And then the people would complain about it. So DNR would look at it and they'd get a timber sale. "Let's get our timber out before somebody complains about it." And so Weyerhaeuser and DNR were basically vying with each other. So I set up a meeting with Weyerhaeuser and I said, "We want to make a land exchange with you. We want to acquire all your land on Tiger Mountain." They looked at me like a cat that’s just about to swallow the canary, like, how could you be so dumb?

And so then I appointed a Tiger Mountain committee to look at the resources of Tiger Mountain and how to manage it, to come back with a management plan for DNR. And they did. And we adopted it. And they all said, "We didn't think you'd adopt it!"

The Mountains to Sound Greenway came from that. And I was one of the founders, with Jim Ellis and Ted Thompson, we were the founders of it. And it doesn't mean that we actually conceived the whole thing. We just signed a paper for it. If nobody did anything like the Mountains to Sound Greenway, people would just nibble away at those edges. See it all the time.

There were other lands, like the John Wayne Trail, which I acquired. I bought it. The Milwaukee Road was going into receivership. Our engineer, the DNR head engineer, was talking about it. And so I said, "Before you retire, I’d like you to do a job, go buy it. The whole thing." I talked to some legislators and they said, "Ah, geez, it goes all the way across Eastern Washington, the farmers are going to go crazy." I said, "No, they want to buy it. They want to own it. You don't want to let them have it. You're just inviting a war over the whole thing. The state should own it." And they agreed on it. So I sent him out with a budget. He went to Chicago, he evaluated the whole thing, he rented a helicopter, and he flew the whole thing and surveyed and photographed the whole thing and looked at all the land ownerships around it and everything like that. And we went to the bankruptcy court and made an offer. They took it. It drove people in Eastern Washington crazy because they always thought that they owned it. And of course, then there's all these John Wayne Trail people who were driving buggies along it and stuff like that. Apparently, they had been doing that for years and they thought they owned it. It was actually kind of hilarious. But it all kind of worked out.