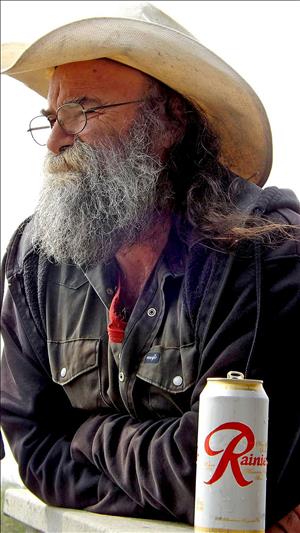

Finn Wilcox (b. 1953) ran away from his Klamath Falls, Oregon, home, at the age of 16 to ride freight trains and pursue his dream of becoming a poet. He found his way to Port Townsend in the early 1970s and joined with a crew of writers, artists, and musicians to create Olympic Reforestation Incorporated (ORI), a tree-planting cooperative. For the next 20-plus years, Wilcox worked with ORI planting trees for the U.S. Forest Service, the Washington State Department of Natural Resources, Pope and Talbot, and Crown Zellerbach. In this May 2025 interview with HistoryLink's Jill Freidberg, Wilcox tells how a chance meeting while hitchhiking led him to his life's calling; describes backbreaking work in the woods; and recites his poem, "On my 10th anniversary as a Tree Planter."

Runaway Poet

Runaway Poet

Wilcox has published and edited books of poetry and essays including Too Late to Turn Back Now and Working the Woods, Working the Sea. He was co-editor at Empty Bowl cooperative press alongside writers such as Robert Sund, Jerry Gorsline, and Tim McNulty. But there was nothing in his childhood to suggest he was going to be a writer.

Finn Wilcox: I was born in San Diego, in 1953, but I was raised in Southern Oregon. I come from a real redneck, timber and ranching, real Western family. That's the household I grew up in. My brother and I were both avid fishermen and hunters, so that was my introduction, even as a little kid, to the outdoors, a lot of camping and that sort of thing.

I've always considered Klamath Falls sort of the butthole of Oregon, and of course I was definitely the black sheep of the family. I was being seduced by the whole hippie movement in a region where there wasn't much of that going on. I didn't really fit into that area very well. In the summers sometimes I would work at Weyerhaeuser doing everything from sweeping to pulling green chain, which is pulling green wood off and stacking it. I learned real early that wasn't for me.

I ran away when I was 16, got caught, took off again, and got away. I didn't see my family for several years after I ran away. Went to Eugene and Portland and Boulder. Then I ended up going to school at the University of Utah, and I was writing. Basically, I wanted to be a poet. I got turned on when I was younger to Brautigan and Rexroth's Chinese translations, and I thought I had a little talent. Made my way back to the Northwest, and I've been here for 50 years, Port Townsend.

A Chance Meeting

In Port Townsend, Wilcox found a city dependent on the Crown Zellerbach paper mill, Jefferson County's largest employer.

FW: In the mid-seventies, you either fished, worked at the mill, or worked in the woods. I mean, that was it. When I got here, Port Townsend, half those places downtown were boarded up. I mean, there was 4,000 people in Port Townsend then, and there just wasn't much you could do to make money. I was 23 or something, and I had caught the freight trains out of Winnipeg, and I was hitchhiking down the peninsula, and an old beatnik type of guy picked me up, Jesse Miller, and he said, "Hey kid, you need some money?" And I had like 40 bucks.

I said, "Sure."

"Ever plant trees?"

"Nope."

"Well, you want a job?"

"Sure."

"Ever plant trees?"

"Nope."

"Well, you want a job?"

"Sure."

He dropped me off in Port Townsend and picked me up two or three days later and I ended up meeting the crew. And it was quite a crew. Tim (McNulty) and Michael Daley, who's another poet, and me and Mike O'Connor, who was a poet, a jazz musician, and a couple of visual artists, painters. I mean, I fit right in, and I was sunk. That was gonna be my life, and it has been.

Day in the Life of a Tree Planter

According to an emptybowl.org profile of Wilcox, he "worked in the woods of the Olympic and Cascade Mountains ... for twenty-five years, planting over a million trees." It was demanding work, not for everyone.

FW: Well, you strap on 45 pounds of trees around your waist. Sometimes it's steep, steep ground, and it's all slash, so you're hopping over stuff, and you're bending down all day, popping trees in, and at least 70 percent of the time you're getting rained and blown on. It's for young people. Probably the most difficult work I've ever done. In fact, all the tree planters I've ever talked to agree it's probably the toughest job they've ever had.

The first crew I worked for was for a fellow named Hop Dhooghe. Did a couple seasons with Hop and then we started a tree-planting co-op here, Olympic Reforestation Incorporated. And that's when we got all the counterculture people together who needed to work and didn't have any other way of making money. What we would do is bid on either federal or state work, for the DNR, and we did a bunch of work for Pope and Talbot, and then we would bid on federal work too, for the Forest Service. That was always high-elevation work, where you're working up in the mountains. That was always my favorite because it was so beautiful. We were always in beautiful spots. So, it was just a matter of bidding on contracts and, if you win the contracts, you got all spring and all summer worth of work, mostly in the Olympics and the Cascades.

You’d be in a place for a couple of weeks. We'd pack up and move to the next contract. You might be able to come home for a night or two, every couple weeks, but basically it was just being out on the units. Sometimes we'd have yurts and people would build things on their trucks. It was pretty funky living. Everybody got better at it as the years went along, but my first year, I think I slept with plastic bags over me. Towards the end of the last six or seven years, I had an old '50s trailer that I called the Love Toilet, and it was a real funky scene, but it had a bed and a wood stove in it, so I was king of the hill.

It was a dream in a way, a dream come true for someone like me at that time. I had some of the greatest times of my life after working my ass off. Then we'd sit around a campfire and start talking poetry or talking writing. These were good poets. This wasn't bullshit stuff. These guys were good poets, Tim (McNulty) and Mike O'Connor and Jerry Gorsline. I mean, these were people who knew their shit and I learned a ton. Great people to turn your poems over to and get it back the next day and sit in your trailer and see remarks. I mean, for me, it was as much a learning experience as a writer as it was being a tree planter. You couldn't separate them. After a while, they kind of were all meshed into one big thing.

And then when we'd have a weekend, a couple of us would jump in a rig and go to the coast, or just fiddle-fart around, go hiking. Tim and I used to take off and go hike somewhere or just go into the closest town and do our laundry. It's kind of cliche, but it really was like a big family after you do a few seasons together.

Tree Planters and Loggers

FW: I've had some great, great talks with loggers in the bar. It could go south on you, too. The tree planters that I was associated with, with the co-ops and stuff, they were all environmentalists, and the loggers weren't. But sometimes you'd sit down and get a couple beers in everybody and start talking seriously about what's going on, and you'd be surprised how many times everybody would agree. There'd be a place at which everybody sort of was able to understand one another.

And everybody had a respect for one another because we were out there doing it. Regardless of your politics, there was this thing where, you know, a wink and, 'Hey, these guys, they may be hippies, but man, they worked their asses off.' That kind of respect. And same with us, 'Well, they may be rednecks, but man, these guys work hard.' I mean, they were really great, salt-of-the-earth people.

But you could also get yourself in a lot of trouble if you weren't careful. It was a lot like that when the spotted owl … yeah, those were, those were pretty touchy times. The loggers were really pissed off. That was a pretty tense time. Kind of like when the Boldt decision happened with the fishermen and there was that real tension. It was a tense time to not only be in the woods, but just to be in the Northwest, and that was probably a time that you'd really, when you're sitting in a bar with the logger next to you talking, you didn't really want to get into it.

So you just learned to love these guys on a different level than politics. And I did. I really did. I remember working this job and this logger took me home. His wife made a big meal. He had three little tow-headed kids, wonderful family. I mean, right out of Sometimes a Great Notion. That kind of a deal. You know, these real, I just, I knew them. I mean, I was raised with people like that.

Butchery and Beauty

FW: It was my first time getting into the backcountry and seeing hundreds of acres gone. It was, it was just butchery. I don't even know how to describe … it was stunning to the heart and soul to see it. You didn't know what greed really meant, until you see something like that, and you get a real schooling on what greed is. So, I never even looked at it as forestry practices. It was just butchery. Sadly, you get used to it, you know, after a few years of working those places, you get used to seeing this utter devastation.

Sure there's big clear cuts, but we'd always camp at the edge somewhere, and, I mean, there was still beautiful country around. It was wonderful, especially the high mountain stuff. I remember the last day I planted trees. I knew I was done. I was one of the last holdouts. Everybody else had gotten into other stuff. I just couldn't give it up, because I knew I would never be in the woods as much as I was. I was 40, which is old for a tree planter, when I quit.

"On my 10th anniversary as a Tree Planter"

Nearly a million trees older now

I remember when my children

Were shorter than me

And the hair on my head was

Thick as a stand of doghair hemlock.

No regrets though,

The friends that I love

Still work by my side.

But sometimes,

On cold, rainy nights,

These stubborn knuckles

Click and hesitate

When I set down the wine.

Nearly a million trees older now

I remember when my children

Were shorter than me

And the hair on my head was

Thick as a stand of doghair hemlock.

No regrets though,

The friends that I love

Still work by my side.

But sometimes,

On cold, rainy nights,

These stubborn knuckles

Click and hesitate

When I set down the wine.