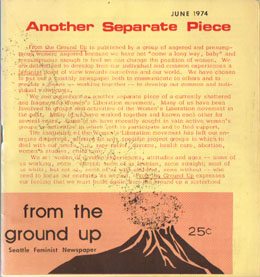

This is a first person account reprinted from From the Ground Up: A Seattle Feminist Newspaper, June 1974. In it, Helen Dunn describes the inequities and gender politics of hospital work in the mid-1970s.

"Women Working as a Ward Clerk" by Helen Dunn

"I am a ward clerk at Group Health Hospital. This involves sitting at the Nurse's Station answering phones, processing doctor's orders, directing people to patients' rooms, and knowing where all the patients are all the time. Ward clerks essentially manage the whole ward, taking the paperwork and all the nit-picky details from the staff nurses. But being a ward clerk is different from working as a clerk in the business office or medical records.

"We accept a great deal of responsibility for people's well being; if we make a mistake it might mean a patient would not receive the blood she needs, not see the doctor in time, not get the help necessary if she goes into respiratory arrest. I didn't have to go to school to be a ward clerk, but my three years of experience make me more effective. I have to be organized, able to work under constant interruption and pressure, and be able to take flack from all sides. I am in the middle. In dealing with relatives of dying patients, for example, I am directly involved with the horrors of illness and death, and yet am totally helpless to change anything: I am stuck with the paperwork and the phones.

Ward clerks at Group Health are all women. (The only male ward clerks I have heard of were interns in the Hospital Administration Program at the U of W, working part-time to pick up on what happens on a typical hospital ward.) Most of us are in our twenties, some our forties; some are married, some have children. Most of us have been here about two years, some longer than five. We have college degrees in psychology, english, music, anthropology, etc. Being a ward clerk is as close as we can get to patient-care without any technical training. We can learn a lot about medicine, but we rarely have time to spend with patients. All of us will eventually leave. Ward clerking is a dead-end job -- it is not a career.

We are supposed to be active members of the "the health care team," and we are paid less that anyone else, and have to deal with all the petty hassles no one else wants. Most of us become ward clerks because of a vague interest in medicine, but have continued working there because we can't find anything else.

Working at Group Health has demonstrated the bizarre methods used in running a hospital, the outdated-but-changing relationship between doctors, nurses, and patients; and a whole group of workers who are grossly underpaid and overworked. Hospital workers are a group that remains invisible to the general public and as such have, until recently, been overlooked by any kind of legislative process or union organizing. The majority of hospital workers are women -- many of them do filthy and uninspiring work. The history of why hospital work (other than administrative) is so low-paying is something that needs investigating. It is because in the past much of nursing was done by volunteer women in service guilds, or was a lowly job left to the dregs of (female) society? Is it because in the past nursing required little skill, or because it has always been "women's work?"

In any case, Group Health is now unionized and the employees make better money than most hospital workers in Seattle. But hospital administrators have a lot of catching up to do. The criteria used for relative pay scales at Group Health are arbitrary and are not based on the amount of patient-care, responsibility, or pressures inherent in any one position. Rather, some positions, like head washman in the laundry, and warehouseman in the storerooms, have salaries based on what these people could earn in the commercial world outside the hospital. Nurses, who have no connection with any job outside the hospital, are paid less. Men just out of the military who have had minimal medex training make more than women who went to school for the same amount of time to learn approximately the same things. Head nurses make a lot compared to these workers, and yet if they were men in similar management positions they would be making thousands more. These present inequities are a great source of anger and frustration among the women who work at Group Health.

Despite these frustrations, tensions, and pressures, I enjoy my work. I am good at it. One reason I stick it out is because my job (and most involving patient-care) is less alienating than many. By alienating, I mean the kind of job where you are a small cog in a big wheel, never realizing the product of your labor, feeling that you are part of a never-ending bureaucracy. I work with people, not numbers or machines. In working with people, even though they are always sick, and some die despite our efforts, I see my labor justified; I have visible proof of what I am working for.

Satisfaction in this work is often bittersweet; we are helpless against a lot of suffering, but we also help people. The RNs I work with are often overwhelmed by the confusing system of medicine as it is practiced in American hospitals. They are frustrated by overwork and the fact that they are too busy to learn anything once they are out of school and working on the floor. But I don't know any nurse who would give up working with people this way for a management job in an office.

There are a great many problems with health care delivery in this county, but I am committed to it, and to becoming a part of a force for change within the system. I have many alternatives: I have applied to nursing school because I am interested in nurse-practitioning in an urban free clinic. I have thought of public health, or medical social work. My hope is that more women who have come up through the hospital system can become a major force in changing the priorities, inequalities, and absurdities of present medical practice.