The health care visionaries who founded Group Health Cooperative in Seattle in 1945 were activists in the farmers' grange movement, the union movement, and the consumer cooperative movement. Their inspiration was Lebanese-American physician Dr. Michael Shadid (1882-1966), founder of the nation's first cooperatively owned and managed hospital (in Oklahoma). Dr. Shadid's crusade was to overthrow the traditional fee-for-service practice of medicine dominated by solo practitioners, expensive specialists, and private hospitals and clinics. Instead he advocated affordable, prepaid healthcare through the cooperative ownership of hospitals staffed by physicians -- practicing as a group -- who promoted the new idea of "preventive" medicine. Group Health Cooperative began providing health care after merging in 1946 with the Seattle-based Medical Security Clinic, a physician-owned group practice whose idealistic doctors also believed in preventive care. After years of struggle and despite virulent opposition by the medical establishment, Group Health became one of the nation's largest consumer-directed health-care organizations. This is Part 1 of a seven part history of Group Health Cooperative.

Planting the Seeds

On the evening of August 14, 1945, four dozen people gathered in the Gold Room of downtown Seattle's Roosevelt Hotel to hear a doctor from Oklahoma named Michael Shadid. It was an eclectic assembly representing labor unions, farmers' granges, consumer and producer cooperatives, and parties and political organizations ranging from lunch-pail Democrats to revolutionary Socialists.

There were also a few plain citizens curious about the speaker and his subject: how to make American health care more affordable, accessible, and accountable.

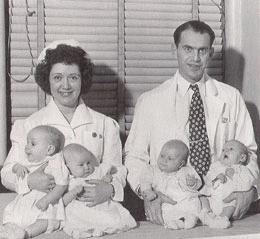

Dr. Shadid had founded the nation's first cooperative hospital in Elk City, Oklahoma. Born in Lebanon and billed as "small in stature, dynamic in nature," Shadid was a peripatetic crusader for health-care reform. In talks around the nation, he promised to expose "dark and unwholesome medical practices and to guide the common people of the United States into a safer, and more economical system of medical care and hospitalization."

A small group of activists had invited Shadid to Seattle to rally support for organizing a cooperative hospital. He was preaching to the choir. Most in his audience had deferred their dreams of social reform and progress through four years of world war, and they were impatient to resume work on building a more equitable, just, and democratic society.

At the end of Shadid's talk, the audience unanimously endorsed his proposals and named a committee representing the attending unions, granges, and cooperatives (see glossary) to draw up a plan for a local cooperative hospital. They exited into the street to the sound of honking car horns, whistles, and cheers. Emperor Hirohito had just signaled Japan's unconditional surrender. World War II was over. The fight for Group Health was about to begin.

From Contract Medicine to Medical Security

In 1945 public concern over the cost and availability of health care was nothing new. Washington state was a national leader in promoting job-related medical care for employees under 1917 amendments to its pioneering 1911 workmen's compensation act.

Employers, labor unions, and fraternal groups such as the Eagles arranged for contract medicine by physicians or clinics at negotiated rates. Drs. Thomas B. Curran and James R. Yocom founded the Tacoma-based Western Clinic in 1916 to treat injured workers under contracts with unions and employers. Dr. Albert W. Bridge also founded a similar doctors' bureau in Tacoma that year and soon extended service to Seattle.

In 1920, Dr. James Tate Mason joined with colleagues Drs. Maurice Dwyer and John Blackford to organize a group practice, a then-radical approach in which doctors from different specialties worked as a team rather than as individual practitioners. Mason and Blackford's daughters shared the same name: In their honor the clinic and small hospital was named Virginia Mason.

The American Medical Association (AMA) and its state and King County chapters abhorred both contract medicine and group practice as affronts to the ideal of the individual physician nobly pursuing his (rarely her) healing arts -- for the highest fee he could get. Traditional fee-for-service physicians, whose charges could vary widely depending on the patient and condition, regarded doctors' bureaus as traitorous.

Despite this, even conventional doctors had to find ways to make their services affordable to more patients. The AMA was concerned enough to endorse the concept of national health insurance in 1916, but recanted four years later. Texas surgeons created the first Blue Cross insurance plan in 1929, and California physicians created the first Blue Shield plan in 1938.

By then, brother industrialists Henry and Edgar Kaiser had taken charge of building the federal government's massive Grand Coulee Dam on the Columbia River through their companies, Northern Permanente and Kaiser Permanente. They hired Dr. Sidney Garfield to organize a health plan to cover 15,000 dam-building employees and their families.

Also in 1938, Leslie G. Pendergast took control of a contract medicine service in downtown Seattle's Securities Building and renamed it the Medical Security Clinic. Aided by administrator Rudy Molzan and a medical staff led by Dr. George W. Beeler -- and a big boost in enrollment thanks to World War II -- Pendergast built the clinic into a thriving practice. To help serve thousands of defense workers and their dependents, he acquired the already aging St. Luke's Hospital on Seattle's Capitol Hill.

To Serve the Greatest Number

Dr. Michael Shadid's Seattle appearance had been arranged by Addison "Ad" Shoudy and R. M. "Bob" Mitchell. Scion of an Eastern Washington pioneer family, Ad Shoudy was born in Cle Elum and raised in Ellensburg. He organized his first co-op, a rural telephone system, at the age of 16, and after that established no fewer than 78 co-ops around the state. He then became manager of the Puget Sound Cooperative, a West Seattle grocery. In 1938, Shoudy was outraged when the local Blue Shield plan refused to cover treatment of two of his employees for "pre-existing conditions" and he was shocked by the out-of-pocket costs they had to pay for needed care.

Bob Mitchell worked as education director for the giant Pacific Supply Co-op, founded in Walla Walla in 1933 to provide farmers with low-cost fuel and fertilizer. His job put him on the road crisscrossing the Northwest to promote the creation of new co-ops, sometimes in tandem with Ad Shoudy.

Mitchell and Shoudy were old friends and allies of Lily Taylor, a leader of King County's Newcastle Grange. The farmer-led grange movement was then a large, powerful, and politically progressive force in Washington state. Founded in the wake of the Civil War, the granges promoted government regulations and rural cooperatives to protect farmers against rapacious railroads, shippers, wholesalers, and other predatory businesses. Granges also supported public education, Prohibition, woman suffrage, and other social and political reforms.

Taylor encountered Shadid's book, A Doctor for the People, in 1939 and passed it on to others, including Ella Williams, a leader in King County's influential Pomona Grange. Williams won passage of a resolution to the State Grange in 1940 urging study of medical cooperatives to cut costs and expand health care.

The following year, Shoudy and Mitchell read a pamphlet titled Cooperative Medicine authored by another crusading physician, James P. Warbasse, the father of the American cooperative movement. They consulted with Warbasse on how to organize a Northwest medical co-op, but before they could act, Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor intervened. The project was shelved for the duration of the war.

With Allied victory assured by the summer of 1945, Shoudy and Mitchell arranged a Pacific Northwest speaking tour for Dr. Shadid and his associate, Stanley D. Belden. More than 2,000 turned out for his talks in Idaho, Oregon, and Washington. Shadid denounced fee-for-service medicine as benefiting only the rich and proselytized for preventive medicine, physician cooperation, and prepaid medical care. His largest audience was in Renton, home of a major Boeing plant and its main union, the International Association of Machinists (IAM Lodge 751, better known as Aeromechanics). The IAM would become a leading force in the founding of Group Health Cooperative.

After Shadid's triumphal tour, a small Seattle Hospital Committee was formed. This group focused on taking over a recently completed federal hospital in Renton, which was likely to be surplussed due to the war's end. Shadid warned the group that physicians, not consumers, would dominate the management of any hospital. He advised them that, "they had better organize health plans."

No doubt inspired by Group Health Association, organized by federal workers in the "other Washington" in 1937, the group adopted the name, Group Health Cooperative of Puget Sound. Shoudy thought this was "too big to handle," but he was outvoted.

On December 22, 1945, the founding Board filed incorporation papers with the State of Washington. The founders included IAM 751 president Thomas G. Bevan, Grange leader Ella Williams, and cooperative pioneers Shoudy, Mitchell, Stanley Erickson, and Victor G. Vieg. Attorney and longtime activist Jack Cluck served as corporate counsel.

Significantly, Group Health did not incorporate as a true cooperative, in which ownership of the organization is distributed equally among its members, but rather as a straightforward non-profit membership corporation. Members had the authority to amend the bylaws and they elected the Board of Trustees that ran the corporation, but members did not own its assets or directly control its operations.

The mission of Group Health, expressed in its original 1946 bylaws, was nothing if not ambitious:

To develop some of the most outstanding hospitals and medical centers to be found anywhere, with special attention devoted to preventive medicine.

To serve the greatest number of people under consumer cooperative principles without discrimination.

To promote individual health by making available comprehensive personal health care services to meet the needs and desires of the persons being served and to reduce cost as a barrier to health care.

To place matters of medical practice under direction of physicians on the staff employed by the Cooperative and to afford strong incentive for the best possible performance on their part.

To recognize other employees of the Cooperative for purposes of collective bargaining, and to provide incentive, adequate compensation, and fair working conditions for them.

To educate the public as to the value of the cooperative method of health protection, and to promote other projects in the interest of public health.

These were lofty aims and a high bar for a brand new organization to aim for, especially when powerful interests were determined to see it fall short.

To go to Part 2, click "Next Feature"