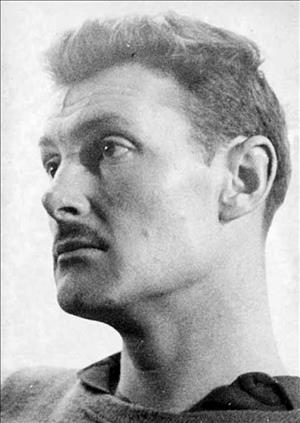

Seattle painter and arts connoisseur Thelma Lehmann describes some of the surprising public antics of famed "Northwest Mystic" painter Morris Graves (1911-2001), a friend and colleague. From Graves' public dispute with fellow artist Kenneth Callahan (1905-1986) in The Seattle Times "Letters to the Editor" section, to his forcible removal for outbursts during a performance by composer John Cage (1912-1992) at the Cornish School of the Arts, Graves never repressed his volatile and eccentric "artistic temperament." Reprinted with permission from Out of the Cultural Dustbin (Seattle: Hans and Thelma Lehmann, 1992).

To visualize myself as a child is a little like reentering time.

In this case, the time was the late 1920s, and through my retroscope I see the hazy figure of myself as thin and unusually tall for my age of 12. It is spring and the sun is making Seattle the best place in the world to live.

On my daily eight-block walk to Seward Grade School, among the houses I pass are two that are unforgettable. Had they not been demolished to make way for the freeway, they might still be held in esteem these 60 years later as historical landmarks -- not because of their architecture, which was ordinary, but because they were the homes in which two of America's outstanding artists grew up. One was the home of Robert Joffrey, who became a master of the dance world, who had shared this house with his Afghan-Italian parents at a time in which he was attending the dance classes of Mary Anne Wells and Cornish School. The other, several houses down the hill, was the home of Morris Graves.

Although, three generations later, the picture has grown dim, I can still see my child-self, tennis racquet swinging in small, loose arcs, standing in front of Graveses' house, calling, " Celia, can you come out and play?" The tennis courts on the Seward School playground have finally dried after the winter rains, and I am breathless to use them. As Celia comes bounding through her front door, another figure appears on the balcony above, a tall, superb-looking young man who looks down at us, silently broadcasting his displeasure.

"Who," I ask Celia as we run off, "is that, and what is he doing up there?"

"Oh, that," she explains, "is just my brother Morris. He's up there painting. He thinks he wants to be an artist." Her answer is a dismissal edged with sarcasm.

An artist indeed! How could I have known then that Morris Graves would become one of our country's most renowned artists? Or, for that matter, that I too would eventually "want to become an artist?"

Celia was only one of Morris's seven siblings, and one wonders how much of his restlessness was a family trait. His nomadic spirit drove him to see at least half of the world, places such as Japan, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, much of America, most of Europe... and La Conner, Washington. I was in my 20s when Stanley Blumenthal, part owner of the La Conner newspaper, took me to see the small town. An hour's drive from Seattle, La Conner had a population of approximately 100 including Morris, who was living in a partially burned-out house, which we visited one afternoon. In the evening Morris arranged for the three of us to be guests at an Indian potlatch. While it was a ceremony that could be occasionally attended by Morris or Stanley, it was a singular visit for me. As I look back on the incident, I wonder if it was beyond the grasp of my mind at the time, since there was much I didn't understand about the ceremony. I think of it as a missed opportunity.

During the war, in the '40s, I saw Morris more than usual. I was working at the Seattle Art Museum along with Guy Anderson and Kenneth Callahan. Morris would show up occasionally for visits. The basic reason for his appearances at the museum was to have conferences with Dick Fuller, who had taken it upon himself to sponsor Morris. Dick could be counted on to buy a painting whenever Morris brought his latest creation for him to see.

One day at the museum, word was that Morris had brought in some pieces of sculpture that were to be sold. The pieces had been done by a young genius, Sherrill Van Cott, who had, within the month, died of a heart ailment at the age of 21. He had been particularly close to Morris, and I felt that I was doing a personal favor for several of my friends by alerting them to the possibility of owning one of these exceptional works. The one I chose was an abstracted figure of polished sandstone, 12 inches in height, which possessed the tragic quality of a Käthe Kollwitz drawing; this work establishes its own aura wherever I have placed it in our home over the last 50 years.

There seemed to be a rigid self-containment in Morris, but also a kindness; I never developed the friendship and affection that I have for Guy or had for Kenneth or for Mark Tobey.

In 1953, I was delighted to see all four artists nationally recognized in a prominent spread in Life Magazine, at the time the country's leading news-picture journal. Included were profiles of each artist, who were then grouped together and crowned with the title of "Mystic Painters of the Northwest." Here in Seattle, we accepted the magazine's description of a Northwest style, understanding that it was one that presented paintings that tended to be mystical and delicate, based on our weather and our outlook toward the Orient. Then, and for long afterwards, the existence of a "Northwest Style" was a matter of hot dispute among Seattle painters.

Of all the artists in Seattle, Morris was the most eccentric.

In conversation with Annette Weyerhaeuser, a longtime resident of Tacoma, I was amused but not surprised to hear a tale of a very independent Morris in his early years. Morris was viewing a show in Tacoma's only gallery, the one that preceded the Tacoma Art Museum, and as he moved from painting to painting, he suddenly stopped. With both hands he removed the painting before him and brought it down on his raised knee with enough force to destroy it. It was a painting that had not been done by Morris.

Whether this was a personal reaction to a painter Morris held in contempt, or whether he considered it merely a bad painting, only Morris could ever say.

Another example of his well-known antics occurred in the days when experimental concerts were held in the auditorium of Cornish School. Morris had gone to hear a performance of the composer John Cage.

Anyone familiar with the contemporary music of John Cage would have expected to sit through typical long passages of silence, but to be watching the methodical destruction of a piano on stage -- that was a new note in experimentation.

From slivers to chunks, when wood is being torn from a piano, it gives off a variety of sounds. Along with hammer blows and the whine of stretched and caressed piano wires, the auditorium was filled with unexpected, unconventional, and mostly unwelcome sounds.

Suddenly, from his place in the audience, Morris thrust himself out of his seat, and with clenched fists jerked skyward, exploded with the cry, "Jesus sees all!"

The ensuing melee, punctuated by other staccato notes by Morris, all fortissimo, threatened to continue until he was dragged along the floor of the aisle and into the lobby.

At that moment, Mrs. John Baillargeon, a grande dame of Seattle who was on her way to the concert, entered the lobby.

"Unhand him," she brusquely directed the students who were subduing Morris.

As he rose, Morris and his rescuer exchanged friendly greetings, and with smiling faces, walked arm-in-arm back into the auditorium, where they resumed seats for the rest of the concert.

Morris's unfettered criticism of fellow artist John Cage had turned into the best performance of the evening!

Another memory, and perhaps the one that remains clearest to me, is how the art community (so small at the time) was enraged after a "party" to which Morris had invited us in Woodway Park, north of Seattle.

He had sent us perfectly enchanting invitations, complete with a map of directions. When the day came, Hans and I, along with artist Walter Froelich and his wife, followed Morris's map, which took us to a path in the woods. We found it blocked by a fallen tree. After climbing over the tree, we walked another quarter of a mile to reach his locked gate. As others arrived, we all stood facing a tall brick wall that surrounded his house, listening to strange unmusical sounds coming from within. But the real show to which Morris was treating us was a depiction of The Last Supper. A long table, sparsely set, with an enormous turkey carcass in the center, was being sprayed by some sort of watering device from above. "Come on out, Morris," called one of the guests. "I can see your camera behind the hole in the wall."

In some uncanny way, the sun was lighting the scene with iridescent rays that could not have been better planned by a Hollywood lighting expert. Nevertheless, according to irate letters in subsequent newspapers, many of his "guests" were made to feel as foolish as we had been.

It was not unusual to spot Morris's name while reading the Seattle papers.

Somewhere during this time, Morris and Mark Tobey wrote each other unpleasant letters. They ran like a serial in the "Letters to the Editor" column of the Seattle Times. Among other things, Mark accused Morris of plagiarizing his paintings. The letters were scattered over a two-week period, a private feud for all to see.

Perhaps it was because of my respect for Morris's painting that I usually stood at shy attention whenever he was around. I sought an understanding of his Zen Buddhist-inspired design -- with light subject on dark, dark on light, it captured the atmosphere, then as now. His statements anchor his pattern with exquisite lines, leaving spaces that all but breathe. Because Morris's paintings included depictions of birds, as well as dense areas of long interwoven, delicate lines, I sometimes heard derisive references to his work as "bottom of the bird cage" paintings.

If Morris had been born in, say, 1950 instead of 1910 as is the case, the exuberant part of his personality, the part that indulged in his capers, might have embraced the use of video, film, constructions, theater performance, etc., as mediums for his art. Instead, with his use of time-venerated ink, watercolor, and oils, his paintings are like the voices of beauty, they speak so gently.

The most recent Graves painting that I've had the pleasure of seeing was at the Foster-White Gallery. A large still-life, all flattened foreground, fastidiously painted, possibly in his current studio in Eureka, California.