Thelma Lehmann, Seattle painter and arts connoisseur, describes Mark Tobey (1890-1976), whom she calls the most visionary of the four "Northwest Mystic" painters. She describes him as petulant and querulous, but also noble and wise, even when confronted with an unbalanced groupie who claimed to be his wife. Reprinted with permission from Out of the Cultural Dustbin (Seattle: Hans and Thelma Lehmann, 1992).

"Mark Tobey isn't home," she shrilled, "I am his wife." She was half seated against the porch railing, dressed in a style that might be called "pleasantly peasant," which was much in contrast to her frenzied expression. It was a day in the late '50s when I had been maneuvering a few of my paintings up the two flights of steps that led to the front door of Mark Tobey's University District house.

This was my first encounter with Helmi Juvonen. I would have been more startled had I not already heard tales about "poor demented Helmi." Despite, or perhaps because of her disturbed mind, she produced paintings that were not only unusual, but seriously interesting. At this point, Helmi was only mildly acquainted with Mark, but suffered the delusion that they were man and wife, a point of misinformation which she shared with almost anyone. Mark was annoyed when Helmi wanted to tag along and was frustrated by her devotion, but he was sensitive to her problem. In a real sense, he was noble about the whole surprising development.

Actually, Mark had been married once. It was in New York. His arrival in Seattle in 1922 was partly an effort to flee from his "mistake" following the divorce. In the coming 54 years of his career, the only other marriage Mark was to have was his painting.

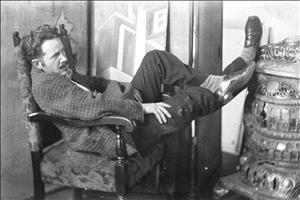

Of all of the artists working in Seattle, Mark Tobey was the most visionary. He was wise, helpful, humane, and -- petulant. He created a field of disturbance with his peevishness, which came out as a sort of counterpoint of small negative reactions to the subjects of anyone's conversations.

His querulousness was fine-tuned one night when he and his agent, Otto Seligman, had come to dinner. It was not difficult to understand its origins. My two guests were sitting under a large, new, and important Kenneth Callahan painting without a single Tobey piece in sight.

Mark spoke through a wounded voice saying, "I'm being so annoyed by calls from the new Show Magazine. They've been pestering me for a profile, and I have no intention of going through all that. I'm working on the Hauberg commission for the Opera House mural, and I don't want the interruption of --"

"But Mark," I interrupted, "it would be a valuable project, I wouldn't mind doing it myself."

In a reflective and uncharacteristic about-face, Mark suddenly acquiesced, saying, "Well, do it then!"

When it was finished, I shoved it under his door for approval or corrections as I had promised. The corrections were never forthcoming and Mark never mentioned it again. I sent it to Show Magazine and received a positive reply with the information that it would be paid for and published "sometime in August or September."

The door under which I shoved the profile led to an average-sized house of early-Seattle architecture in which Mark had been working, teaching, and living since the 1950s, most of the time with his housekeeper-companion and art pupil, Pehr Hallsten.

I was in my mid-family years and I remember well our discussions about art, and my appreciation of his ability to look into the intentions of my paintings. Whenever I was inspired by a painting that I had seen, I held the after-view like a continuous thought, which was not distilled until I'd had time to apply it to canvas, sometimes a matter of days. If I could pacify the household digressions -- dutifully attend to a permissible number of parties, of concerts, of meetings -- I would secretly get to my studio again, and produce a work to show Mark and thereby gain a treasured opinion. His understanding, his question, "How do you have time to paint at all?" touched the quick of my thinking.

Mark's life was a time-keeping mission. His hours were divided between his privacy and his work, with a small allotment spent with friends for good balance. Mark didn't always count the local artists among his friends, but had good relations with some, notably Windsor Utley, Betty Bowen, Pat Nicholsen, and Wesley Wehr.

Mark was not only an artist on canvas, he was a master of observation and insights about life -- an eminently quotable man. Wesley Wehr notes that Mark once told him, after a bout of world-weary philosophizing, "Oh, I don't know -- this business of being happy can get out of hand!"

Mark was always concerned with keeping his work fresh and honest. In 1955, he stated, "When an artist starts to repeat himself and ceases to be engaged in the problem of equilibrium, of balance, then he is a career painter. When his problem is always vital and present, then he is an artist."

Mark treasured his close friendship with the famous artist Lyonel Feininger and believed him when he complained, "For the first time in my life I've become self-conscious. This is a terrible thing -- for an artist to be self-conscious. Then he is like a centipede which becomes aware of all its legs and starts tripping over them."

Mark must have related to such a disclosure, and quoted his Zen master, who had advised that he "Let nature take over your work. Get yourself out of the way when you paint."

And I can still see Mark's wry expression when he said, "A watched pot never boils, and painters who are watched go to pot."

I wonder if Mark ever suspected that there could come a time in which dedication to painting from the inner self would evolve, some 40 years later, into just the opposite -- a time in which the art of self-promotion would be as important as the art itself.

What was it that placed Mark's work in the forefront of international painting? Were his paintings immediately striking and appealing? I don't think so. On the contrary, they demanded more than the usual patience and understanding on the part of the viewer. As every artist searches for his particular message and his particular language with which to state it, Mark too made decisions that were to become intimate only to him.

It was in Devonshire, England, in 1935, when he returned from the Orient and was in such admiration of calligraphy that, by replacing calligraphy's language of squiggles with constantly repeated delicate straight lines, he went on to interpret the frenetic rhythms of a modern city, the lights of threading traffic, the streaming humanity in space, the flow of weaving light. If these paintings at first glance look like stenciled wallpaper, another look would reveal an activated surface, filled with energies and vibrating space.

Although this technique of "white writing" was the innovation for which Mark was best known, he never allowed himself to become locked into a mold. He did paintings, both before and after his signature period, as subject-oriented as the portrait of Mrs. Edgar Ames, the Public Market Types, or his powerful Japanese ink (Sumi) Heads.

Mark's international reputation began to grow after 1950 when he was already in his 60s. He had become a patriarchal figure. People in the arts know Mark mostly as the first American since Whistler to win a gold medal at the Venice Biennale (1958) and as the rare American who gained the world's signal honor by having an exhibition of his paintings in Paris' Louvre.

The powers that were the Seattle Art Museum invited Mark back to Seattle from Switzerland to celebrate his 80th birthday with fanfare, adulation and a retrospective of his paintings in 1971. I am pleased that I have saved the catalogue of that exhibit, for as I see now I find it as beautifully assembled as was the exhibit. Mark lived another five years after that, and died in 1976 in Basel -- the city that he had chosen as his second home.

Although the names Tobey, Graves, Anderson, Callahan, and Dr. Fuller are now the stuff of legend, they will always live for me as reminders of the years in which our little Northwest corner of the country became part of the fabric of the world history of art.