Seattle painter and arts connoisseur Thelma Lehmann describes painter Kenneth Callahan (1905-1986), one of the four "Northwest Mystic" artists, and a close personal friend. This group of painters included Mark Tobey (1890-1976), Morris Graves (1911-2001), and Guy Anderson (1906-1998). Reprinted with permission from Out of the Cultural Dustbin (Seattle: Hans and Thelma Lehmann, 1992).

On a day in 1958, Margaret Callahan and I walked into the studio of her artist husband, Kenneth, to see him standing in front of a large painting that he had just completed. It rested on his easel, dazzling in its fully orchestrated color. What a sudden change for Ken, who had long been known for his palette of browns and ochres rather than the light flowing grays, yellows, and brilliant reds of this canvas.

"Oh," I gasped, "It's marvelous! I wish I had waited before buying a painting of yours, because I'm stuck on this one."

"It's perfectly OK," was Margaret's prompt reply, "if you want to exchange this one for yours."

The painting, titled simply Figures, has dominated various walls in our home ever since.

Did it seem strange to me that Margaret had not so much as glanced at Kenneth before disposing of his last work in such a cavalier manner? Not really. I had already learned that when it came to Ken's painting, they were as one.

Of the five principals in the early art world of our city about whom I write here, it was Kenneth Callahan for whom I had the most affection. Although I have been assured that he had flaring moments of anger, I had never been privy to any of them, and always saw him as quite agreeable, even in his painting critiques, whether in newspapers or magazines such as Art Digest.

One Sunday afternoon sometime in the 1950s, Hans, our baby son, Spencer, and I drove to Granite Falls to visit the Callahans. Son Toby (Brian) Callahan (Ken had always denied that he had been named after Mark) had become a young huntsman, and at dinner that evening I tasted my first bear meat, shot and dressed by Toby and cooked by Margaret. It was tender and slightly sweeter than the beef we were used to.

The rough-hewn cottage near Granite Falls was attached to yet another studio for Ken, surrounded by mountains that proved to be the inspiration for his paintings and drawings -- drawings in which one finds a breathtaking sensitivity of line.

This studio, stacked with years of loving effort -- drawings, paintings, metal sculptures -- was lost when, in 1963, it burned down. A catastrophic time for Kenneth.

Margaret was not a painter, but her open mind had a fresh eye for painting. She had been a newspaper reporter and editor. She wrote poetry and was an insatiable reader. She had become the motivator, the trouble shooter, for Ken's seven-hour, seven-day painting schedule. "I can think of no other reason to paint than there has never been anything else I would rather do."

Margaret has become den-mother to a Callahan coterie of painters that originally included Morris Graves, Mark Tobey, Guy Anderson, William Cumming, Lubin Petric, Malcom Roberts, and Fay Chong. By the early 1940s, each had gone his own way, but I can only guess that their exposure to the Callahan's congenial group polemics was as sustaining to them as it was, later, to me. I learned that no idea was too idiotic to be thrown forth for testing in these sessions. It was usually treated with benevolence and guidance by Margaret. (I can remember wondering if her slightly nasal sounding words had anything to do with her straight and ample nose.)

My own painting demons aside, Margaret's nurturing made me feel cherished. Years before her death from cancer, she had settled in my mind as my perfect role model. Her absence ended my presence among the group -- it was she who had set the atmosphere. If these critiques continued in any form at all, I can't say.

But it was Kenneth who was responsible for my five-year battle with the typewriter. It was at the home of Fred and Connie Jarvis, the only ones of the Callahan group with whom, in this year of 1992, we can still hold hands. We were all congratulating Ken on his coming year of travel in Europe as curator of a U.S. State Department tour that included his own paintings along with those of other American artists.

He spoke ruefully about leaving his job as art critic for The Seattle Times. It was during the convivial after-dinner dessert time that he approached me, coffee cup in hand, and suggested that I take over his newspaper column. "I've heard you rummage into the contents of paintings," he explained. "This is your chance to make it functional."

A provocative offer indeed! "But," I demured, "I've had no background in writing."

"Just say what you think," was his solution.

And so we made a pact.

For the next five years, I produced columns of my viewing assessments and handed them to John Vorhees or Lou Guzzo (1919-2013), my "bosses" at The Seattle Times. It was not yet the age of the ubiquitous computer, and a simple correction or two would require rewriting the whole page, again and again.

As challenging and time-consuming as this task was, I thoroughly enjoyed it, especially my two-week journalistic effort in the Soviet Union, where I interviewed artists about the state of the arts in their country, reviews that were published in the Seattle papers. Socialist realism was official, any other visual art was neither subsidized nor exhibited. Still, because Khrushchev was in power, the party line was a little more flexible than in the Communist past.

I sympathized with young, eager Russian painters who, during welcoming evening gatherings in their one-room "apartments," thumbed through contraband American art magazines, demonstrating to me that they were aware of the abstract-expressionist painting being done elsewhere. Later, in my Seattle studio, I found myself painting large splashy oil heads based on my after-vision of some of this affectionate group of Soviet artists. Two from this series of canvases were sold four years later from an exhibition of my paintings in Tokyo, Japan.

When Kenneth returned a year later, he, in his soft and subtle way, didn't ask to have his column back, and I didn't really offer it to him. When I was finally ready to relinquish it so that I could go on to other things, Kenneth had moved to Long Beach, Washington, and was no longer interested.

A few years earlier, 25-year old Beth Gottfredsen had come to Seattle from her home in Denmark with only her adventurous spirit to guide her. In want of employment, she answered a help-wanted ad, and soon found herself taking care of Margaret Callahan's aging father. Who could have imagined that Beth would, a few years later, become the second Mrs. Kenneth Callahan.

After the tragedy of Margaret's death, the daily chores of the family seemed to fall to Beth, who more and more found herself in the position of clearing time for Ken to paint, and also, on occasion, of acting as a sounding board when Ken chose to express thoughts about his work. As they sometimes stood contemplating his painting, possibly in an effort to air his own judgement, Ken would ask, "What do you think?"

If Beth was not entirely approving, he would respond, "I didn't ask for your opinion!"

Kenneth and Beth spent 22 devoted years together as husband and wife, until his death in 1986 at the age of 81.

Aside from his repeated subjects of mountains and horses, he painted elusive human figures, entwining and flowing with the main thrust of his rhythms. Since his paintings, starting when he was about 15, had evolved like bricks in a wall -- one painting built upon the experience of the last -- his pattern was to declare his most recent work "the best I have ever done," or sometimes even "a masterpiece!"

But he was never as sure of himself in assessing the market value of his work. When Miss Kraushaar, his New York agent, would phone to say that she had just sold one of his paintings for a large sum, he would turn to Beth, and in a tone of pure wonder ask, "Can you imagine anyone paying so much?"

I can still visualize Ken and Beth in their home and studio in Long Beach during a visit in the late '70s. What a studio it was! Fronted by miles and miles of glorious beach and sky, the studio attached to their home was about the size of two large barns, organized with enough fresh paint tubes and clean brushes to keep the art stores out of stock for years. It was a studio that must have been the envy of any artist. A 20-foot tall-painting, destined for the lobby of the first Seattle Repertory Playhouse, was fastened at the ceiling. A ladder stood in front of it waiting to be used for the work's completion.

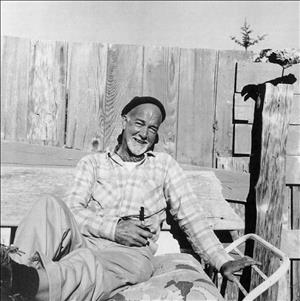

It was one of our many visits to the Callahans, Hans and mine, that remains fresh in mind. Ken was still in good health, thin, tall, amicable as he balanced slightly from foot to foot. He was a gem of a person, instantly gentle and caring, one of those artists who was admirable both as a technician and as a human being.