Thelma Lehmann, Seattle painter and arts connoisseur, recalls a lunch meeting with Guy Anderson (1906-1998), a Northwest painter and member of the "Northwest Mystic" School including Mark Tobey (1890-1976), Kenneth Callahan (1905-1986), and Morris Graves (1911-2001). Guy described these artists' similar styles and influences on each other. Reprinted with permission from Out of the Cultural Dustbin (Seattle: Hans and Thelma Lehmann, 1992).

One day, while viewing an exhibition at the Seattle Art Museum, I saw a landscape painting, Sharp Sea, the work of Guy Anderson.

I was so impressed that I bought it, or thought I had, until the next day when Guy phoned to say the museum had chosen to purchase the same painting and asked, "Would you mind choosing another?"

Did I mind? I don't know. But I did choose another, a slightly smaller oil entitled Clouds and Sea. These were the only two paintings that Guy had ever done in that particular genre.

As it turned out, it was a felicitous arrangement, since in addition to having mine on hand, I can view my first choice at any time in the gallery of Northwest painters in the new Seattle Art Museum.

Clouds and Sea was on prominent display in my home when Guy and his devoted friend Deryl Walls came for a visit recently.

Guy Anderson and I had not made contact for the past several years, and as we settled over lunch, I listened to 85-year-old Guy speak in a voice I remember well: strong, sonorous, with sentences that end in an upswing.

Time raced backward as we spoke of many things: of how it was for Guy to grow up in the small lumber and fishing (now tourist) town of Edmunds, Washington, where he was born; how when he was in grade school he was sculpting little wax figures, attending a one-room school house (from which he was absent for a year in order to work in his father's lumber company); giving piano recitals, painting local theater backdrops, and going fishing. Shades of Huckleberry Finn!

We spoke of how, after World War II, Guy had finished his stint in Uncle Sam's navy and settled for a time in Seattle. He was seriously becoming an artist and fondly remembers that Roland Terry, then the city's most acclaimed architect, purchased Guy's first sketches.

We were nostalgic about how, with the physical strength of our youth, we could drag our paintings through the doors of galleries and museums for competitive shows, and about how some among us -- those to whom art was the only way of life -- became friends.

It was generally conceded that it was Mark Tobey who had originated the mode of paintings that had become known as "white writing," and some, especially Kenneth Callahan and Morris Graves, admired it to the extent of letting it have an undue influence on their own work. Guy noted how pervasive the style had become. He told how one time he had entered a gallery and "saw at a distance a small work that I recognized as a Tobey. As I got closer I knew it was a Callahan and I stopped before it. I could see, including the signature, that it was a Graves."

"Kenneth," continued Guy, "recognized the effect on his own painting and worked through it to find his own painting language -- and so, in fact, did most of the others who were too deeply influenced by Mark Tobey's style."

Before Mark Tobey had been recognized in any substantial way, Morris Graves was being celebrated with a solo exhibition at the San Francisco Legion of Honor and in New York at the Willard Gallery. Mark was adamant in his provocative claim that Morris's success was based on plagiarizing Mark's style. But whatever the case, the importance of what remains of this period of fledgling ideas are the paintings that grew out of it and can be seen throughout the world.

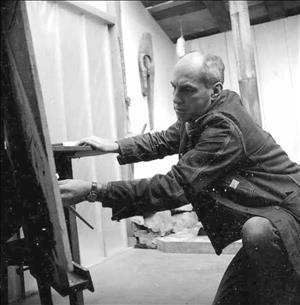

More than most, Guy Anderson has pursued his own artistic course in his own way -- no undue influence of the "action painters" led by Jackson Pollack, or the wildly painted abstract-expressionists à la Willem de Kooning of the 1940s and 1950s. Instead, he paints with technical integrity his conception of an expanded creation, an art seen as a part of a connection between life, nature, and beyond.

His images surface onto the canvas or building paper or board in large sections of form combined with characteristic agents: sea, sky, animals, the naked human form denoting the intimacy and power of man.

Heavily symbolic, with values more pronounced than color, his inner vision defines outer nature and the pulse of the Northwest. His is not a spontaneous expression but one of order, restraint, strong forms that echo his personality.

Several Anderson murals enhance the architecture of public buildings throughout Washington State, from the county courthouse in Mount Vernon to the lobby of Meany Hall in Seattle. In the latter hangs a triptych, Sacred Pastures. Some paces away hangs a painting of mine titled Garbed in Shining Dress. Both often give me more pleasure than the concert I've gone to hear.

Guy's home in La Conner has a vast studio on the second floor. He climbs the stairs daily, "If only to see what I'm working on."

There is a well of adrenaline in many artists that accounts for long and productive lives. Unlike Picasso, Guy is a great favorite among the citizens of his town. Like Picasso, who painted steadily until the age of 92, Guy is constantly looking forward to his next painting.