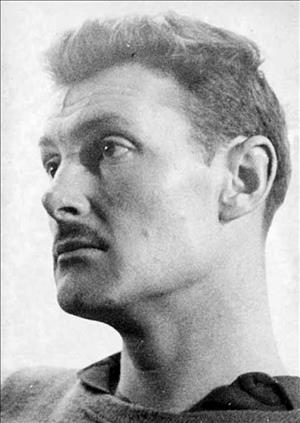

The painter Morris Graves was certainly the most eccentric of the "Northwest Mystics" -- artists of the Northwest School that also included Mark Tobey, Kenneth Callahan, and Guy Anderson. Graves was an idiosyncratic artist from the beginning, going about life in an interesting, just out-of-societal-bounds manner. Burdened by early fame, then just as quickly disparaged, he chose to separate himself from society in his quest to paint symbolic representations of consciousness. For him, consciousness often assumed the form of a bird, or of a chalice. This biography also tells of the homes Graves built and created: his unsung, unseen masterpieces. It is reprinted from Deloris Tarzan Ament's Iridescent Light: The Emergence of Northwest Art (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002).

Northwest Born

For Morris Graves, the softness of Northwest light was a given. He understood its moods in his very pores.

Graves's family moved to the Seattle area in 1911 from a homestead farm in Fox Valley, Oregon, when he was a year old. His mother said, "He was a beautiful baby -- big brown eyes and dark hair, with a little faraway look in his eye -- and very friendly. We named him after Morris Cole, our favorite minister." She had prepared a pink layette, certain that after five sons, this would be a daughter.

She noted in his baby book, "He first laughed on Oct. 3; his first tooth appeared on Jan. 17, 1911, and his first word the following September was ‘See' " (Wally Graves). By then the family had returned to Seattle. The Oregon homestead farm lay abandoned, having lasted little more than a year, bankrupting his father's once-thriving paint and wallpaper store in Seattle.

Born An Artist

Morris is remembered as a moody child, repeatedly ill with pneumonia. He amused himself during recuperation by watching birds and mentally designing gardens. By the time he was 10, he could recognize and identify as many as 40 kinds of wildflowers. He entered wildflower bouquets in competitions at country fairs when he was between the ages of 10 and 13, and he arranged flowers for the Methodist church he attended with his family. His mother remembers an eight-foot-high Easter cross covered with flowering cherry blossoms that he made for the church when he was 11 (Kass).

Years later, Graves recalled that he was 10 when he first felt strongly about an artist. A picture spread in Century magazine showed allegorical murals painted at Yale University. Although Graves could no longer remember the artist's name, the murals lingered in his mind: "There was something about the volume of those forms on a two-dimensional plane that impressed me greatly" (Kuh).

Teenage Travel

Graves dropped out of high school after his sophomore year. With his brother Russell, he applied for a job as a cadet on an American Mail Line ship, sailing to Manila, Japan, China, and Hawaii. He sailed on three such trips, the last in 1931. Morris explored Japan as extensively as shore leave would allow. His impressions helped to make Asian aesthetics a presence in his art from the beginning: "In Japan I at once had the feeling that this was the right way to do everything. It was the acceptance of nature -- not the resistance to it. I had no sense that I was to be a painter, but I breathed a different air" (Soby Interview).

He and a friend stowed away on a steamer bound for New Orleans in 1930. He stopped en route in Beaumont, Texas, to visit his maternal aunt and uncle, Charles and Louise Terrell. They persuaded him to stay with them long enough to finish high school. He was 20 when he registered as a junior. He liked to go to school barefoot. One of his teachers recalled, "He was so fascinating that some students followed him around to observe his interesting antics" (Kass). He served as art editor of the school annual, Pine Burr, his senior year, decorating it with bird motifs.

After graduation in 1932, he spent a summer in New Orleans before returning to Seattle. George Tsutakawa remembered him showing up at Broadway High School around the lunch hour with his sketch pad. Once, George asked whether he could look at it. Graves had filled the pad with sketches of every fire hydrant on 1st Avenue from Yesler Street to Olive Way. When George asked why, and whether they weren't all the same, Graves replied, "Every fire hydrant has a different character, different color, different texture, and some are leaning. They're all different" (Callahan papers).

He made his first mark as an artist in 1933, when he won the Seattle Art Museum's (SAM) Northwest Annual Exhibition, the major regional art event of the year. The painting, Moor Swan, was a symbolic self-portrait, depicting the regal, aloof black swan smoldering in a dusky field. One glance and you know that swan feels misunderstood; that he holds secrets. The painting was purchased for the museum's permanent collection.

"Graves had developed his style from the minute examination of moss, and the study of scaly surfaces of old barns, and used loose painting with a palette knife on coarse absorbent canvas hoping to attain the quality of antiquity of old frescos," Elizabeth Bayley Willis observed (Willis papers, 1-2). Willis, a longtime friend, helped bring Morris Graves' work to national attention first in the Northwest, by showing it to gallery owner Marian Willard, then when she worked at the Willard Gallery in New York, and later as acting assistant director of the California Palace of the Legion of Honor in San Francisco.

The Northwest Light

The look of transparent duskiness that marks so many early Graves paintings may well have emerged from wilderness evenings. At Northwest latitudes, summer sunsets can last for as long as an hour. The effect is unknown in tropical areas, where the sun plunges over the horizon in brief red glory.

Northwest twilights linger. The sky glows a deeper blue as the low sun spills golden light against trees and walls. This light is in no hurry. Gradually it deepens, until finally the sun slips down as if reluctant to leave. Malcolm Roberts, active as a Surrealist painter in the 1930s, called this daily magical interval the "Hour of Pearl." French painters know a similar phenomenon on the Riviera as l'heure bleue.

This long leave-taking of light is a time of transformation. Such light is visible in Graves's early paintings, which seem to be set neither at night nor in daylight, but in some charged intermediate illumination. They carry a sense of consciousness transforming and refining itself to more idealized levels. Faint perfect forms echo crisp imperfect ones; gray shapes spill into color. They are permeated with longing.

The Studio and the Studio Fire

In 1934, Graves built a small studio on family property near Edmonds. It burned to the ground on December 30, 1935, destroying nearly all of his work to that point, as well as his collection of Asian art objects. "Graves and a group of painters held a house warming [for an addition to the studio] then left for town. Neighbors discovered the studio in flames and watched the unfinished painting of a great horse burn on the easel, along with the entire contents of the studio," Willis recalled (Willis, 1-2). Perhaps to help offset the loss, he was offered his first solo exhibition at the Seattle Art Museum.

Spiritual matters would seem to have been much on Graves's mind. In the early 1930s he had begun to attend the Buddhist temple in Seattle, and to be introduced to the concept of Zen, and the meditative goal of stilling the mind to raise consciousness.

Pilgrimage to Harlem

He spent five months in New York beginning in January 1937, taking refuge at Father Divine's Mission in Harlem, where he was given food and lodging -- economies that made living in New York possible for him. Guy Anderson's mother had told him about Father Divine, a charismatic Harlem preacher who pronounced himself "God Made Flesh" to lead the chosen people out of the economic disaster of the Great Depression (Cumming). While he was in New York, Graves washed dishes, worked in a laundry, and sketched animals at the Bronx Zoo, giving the sketches nostalgic Northwest backgrounds.

Graves returned to Seattle in May, and soon after bought 20 acres of land on Fidalgo Island at a tax sale. The price was $40.

He lived briefly in La Conner, where he and Guy Anderson shared a cabin that had been badly charred by fire. They carted beach sand to cover the floor, used candles and oil lamps for light and driftwood for tables. Graves's paintings from the period were symbolic chalices and snakes and the moon. He provided for himself by selling wildflowers and forest greenery to florists. Soon enough, he was back in Seattle.

Tobey, Before the Animosity

He joined the WPA Federal Art Project in 1939, but stayed for only a few months. His paintings while working for the WPA were done in brilliant reds and black, painted in tempera overlaid with beeswax from a hive at his place in La Conner.

It was while working for the WPA that he met Mark Tobey, who introduced him to the use of tempera on Chinese paper. Tobey, who was 20 years his senior, shared many of his interests. Impressed with Tobey's calligraphic line, Graves used a similar web of white lines in paintings of birds to depict gauzy light. Tangled white strokes fall in thick curtains around Bird Singing in the Moonlight and Shore Birds Submerged in Moonlight. The web assumes transparent trapezoidal forms, and seems to represent birdsong in the 1941 tempera painting Varied Thrush Calling in Autumn.

William Cumming recalls, "Graves was living at Tenth Avenue and Washington Street in a place that had been luxury apartments at the turn of the century. It had three rooms; living room in front, a middle bedroom, and the kitchen in back. He had a lot of driftwood scattered around" (Cumming).

Elizabeth Willis noted:

“There was a big vacant house where Morris and his sister and Lubin [Petric] lived. Al Banner went by, and all the shades were drawn, and a chink of light was coming out from one window. He looked in and saw a park bench in front of the fireplace, with Morris and the two sitting on it roasting a tiny piece of meat over the open fire. The room was decorated by Morris with great tall sunflowers and corn stalks” (Willis papers, 1-2).

One of Graves's frequent companions during the time he worked under the WPA was Lubin Petric, who was at that time the domestic partner of Graves's sister, Celia. Lubin, who was of solid Serbian stock, was himself a gifted painter, but his talent was lost to alcoholism. He regularly painted work in the style of Tobey and Graves -- work that easily passed for paintings by those artists, especially since during the 1930s Graves did not usually sign his work.

Graves was too restless to stay long in one place. When he left the WPA in 1939, he went to the Virgin Islands and to Puerto Rico. He returned with a chest full of beautiful rocks, and paintings he had done of fighting cocks. He applied for a Guggenheim grant, but was turned down.

Building The Rock

In 1940, Graves became a friend of George Nakashima, an architect who had just returned to Seattle from Japan and set up a furniture workshop. He and Graves shared the belief that form should grow from the natural properties of materials. That same year, Graves began building a house on his Fidalgo Island property. He sited it on a precipitous outlook reached by a trail barely more than a rut. He had to fetch water in his Model A truck from a service station two miles away. His friend Nancy Wilson Ross wrote:

“No stranger could have found it undirected, for the road that reached it was little more than wheel tracks through a forest, leading at the end up a discouragingly steep slope to a rounded mossy plateau whose stony slopes pitched down hundreds of feet on all sides. On this little plateau there were noble trees and, from various vantage points, breathtaking views. Even the outdoor privy Graves built faced the full sweep of the snowcapped Cascade Mountains, while the small house commanded other vistas far below: wooded shorelines, a hidden lake, and further off, one of the many meandering channels of Puget Sound. One entered the house by way of a Japanese style garden: sand, wind-twisted trees and arrangements of several rocks so enormous one could hardly credit the fact that Graves had brought them up here” (Ross).

Nancy Ross, author of several books including Buddhism, a Way of Life and Thought (1981) and Joan of Arc (1999), introduced Graves and his work to Marian Willard, who became Graves's New York dealer and greatest cheerleader.

Graves called the place The Rock. Over time, he added rooms strung out in single file facing a rock ledge. A few of the windows were covered with rice paper to capture the shadows of tall pines -- an image that appears in some of his paintings of that period.

Life at the Rock

Beginning in September 1940, Graves worked at the Seattle Art Museum. It was Dr. Richard Fuller's practice during this period to employ artists for light duties, to provide them with some income while allowing them time to paint. Graves alternated two weeks on duty at the museum with two weeks off to paint and work on his cabin. That arrangement continued until 1942.

At The Rock, he lived with his Swiss dachshund, Edith, as his companion. (It was Graves's habit to call all of his pets Edith, in honor of poet Edith Sitwell. If he had a litter of cats, several dogs, and a few crows with clipped wings, all bore the same name.) He meditated, painted, and listened intensely to night sounds, trying to imagine and to draw the creatures that made them. At various times he tried to paint birdsong, and the sound of surf, in consonance with the Vedic concept that sound and form are synonymous. Much of his life there was nocturnal. When the weather was conducive, he walked outdoors until midnight, then returned to the cabin to paint until morning.

During this time, he completed some of his most important paintings, including the Inner Eye and Maddened Bird series. It can be deduced from paintings such as the 1944 Bird Maddened by the Length of Winter, with its morose, desperate eye and the suggestion of frost spilled across muddy green, that solitude had its downside during dark winter months when he felt at the mercy of the environment.

It has been said that many of Graves's paintings sprang from visions received in meditation. It might be more accurate to say that for Graves, painting was itself a meditative process.

That exercise of the inner eye did not leave him bereft of puckish wit or energy. In some respects, his heart belonged to Dada. He gained a minor notoriety for outrageous pranks, such as one in 1937, in which he filled a baby carriage with rocks, made a trailer for it of toothbrushes, and pushed it into the dining room of the Olympic Hotel. There, he placed a rock on each of several chairs around a table, and sat down to order dinner.

Graves shunned an audience for his work. He was initially reluctant to sell it. Only combined persuasion from Dr. Fuller, Tobey, and other friends induced Graves to send his work to the Willard Gallery in New York when Marian Willard first requested it in 1939.

The East Coast Comes Courting

Dorothy Miller, a representative of New York's Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), saw Graves's work on a trip to Seattle and asked to include his paintings in a MoMA exhibition. Graves flatly refused. But then, fortunately, he allowed himself to be persuaded. His work was part of MoMA's 1942 exhibition 18 Americans from 9 States. MoMA acquired an astonishing 11 of his paintings for the museum's permanent collection -- an unprecedented splurge for the work of an unknown artist. Not only did all 19 of his paintings in the show sell, but so did an additional 26 pieces not on exhibit, many of them to museum staffers.

Graves had his first solo show that year at the Willard Gallery, in New York. He was also featured in Three Americans: Weber, Knaths, Graves at the Phillips Memorial Gallery in Washington, D.C. All but one of his paintings in that exhibition sold. He was the new sensation. His 15 minutes of fame had arrived.

At that time, most of Graves's paintings were focused on birds, which one reviewer described as "bathed in ectoplasmic moonlight." The birds were touched with strangeness -- blind, wounded, or immobilized in webby surroundings. Graves often intensified their images by making eyes and beaks larger than life, or placing them oddly. One Guardian bird received a set of antlers. Bird Singing in the Moonlight had two heads.

Graves wrote of Bird Singing in the Moonlight:

“The Tobey-like writing and geometric forms in which the bird is submerged was a conscious attempt to poetically help materialize a molecular content of moonlight, to bring it into touchable proximity ... a moonlight impregnated with messages. The bird was given two heads because of its divided emotion-ecstatic song, or humility and silence in the presence of moonlight; a linking of joy and despair” (Graves to Willis, April 30, 1944).

By incorporating "white writing" into narrative interpretations of nature, Graves used it in more metaphorical ways than did Tobey. In his hands, it suggested a quality of consciousness.

Graves's wounded birds touched a place in the collective psyche of Americans newly engaged in war. They also speak to Graves's state of mind at the time. Gerald Heard, writing on the subject of Graves's symbols, notes that "in all significant painting from Catal Hüyük to Hieronymus Bosch the Bird has stood for that drive or force which bears the migrant soul of man into another state" (Heard).

Resisting the Draft

In 1942, with construction of his house at The Rock still unfinished, Graves was drafted into the army. He had registered as a conscientious objector, but when he reported for a physical examination, he was told that he hadn't followed proper procedure by requesting a written review of his application, and that now it was too late to do so. He refused to take the oath of allegiance, and attempted to leave the group of inductees waiting to be transported to camp. M.P.s took him directly to the stockade. When they released him, he walked out of camp and returned home.

George Nakashima and his wife, Marian, were staying with Graves's mother preparatory to being taken to the detention camp at Minidoka, Idaho. When M.P.s arrived there to take Graves into custody again, he took leave of the Nakashimas with an embrace. Back at the Fort Lewis stockade, he was challenged about collaboration with the Japanese, for having embraced George and kissed Marian Nakashima on the cheek in saying goodbye.

He was sent to Camp Roberts in California, which he referred to in letters as a "zone of evil." He called it "a regimental life and public toilet atmosphere." He deeply missed his dog, Edith, which he had left in the care of Elizabeth Willis. He wrote letters to the dog as well as to Willis. He spoke longingly of the Northwest, missing "the heavy rain on the roof, and the wonderful blue luminosity over the Sound at dusk" (Graves to Willis, January 19, 1943).

Later, he wrote, "We must so live that we can sensitively search the phenomena of nature from the lichen to the day-moon, from the mist to the mountain, even from the molecule to the cosmos -- and we must dream deeply down into the kelp beds and not let one fleck of the significance of beauty pass unappraised and unquestioned and unanswered" (Graves to Willis, August 17, 1942).

Graves's military career was brief. An attorney retained by his mother learned that authorities questioned Graves's sincerity as a conscientious objector because of his time with Father Divine (Willis papers, 1-1).

Even had he not been opposed to war on principle, after the quiet and solitude and utter freedom of The Rock, the noise and crowding and discipline of army life could have seemed like nothing short of hell to Graves. At Camp Roberts, he became deeply depressed. He attempted to deal with it by building a wall of seclusion around himself, refusing to communicate. In December 1942, a camp psychiatrist concluded that Graves could not adapt to military service, and recommended that he be returned to civilian life. Instead, he was returned to the stockade, where he refused to shave or to work. He was finally released from the army on March 1, 1943, with an honorable discharge, which he verbally rejected (Kass).

He wrote to Willis, "I am coming home home home home home home home home home home HOME. Dear God make me understand the magnitude of that privilege" (Willis papers, 1-1). He arrived home in the middle of March 1943.

Kenneth Callahan is said to have been furious with Graves for avoiding military service. "He still hates Morris for this and also took Mark's side of the battle, and in the end they all hate each other," Willis noted in her journal (Willis papers, 2-13). (The conflict between Tobey and Graves was rumored to concern Graves's recognition in New York for paintings using white writing before Tobey had had a New York exhibition.)

Graves All the Rage

Graves's career was in high gear. He painted the Morning Star series (based on Revelations 2:25-28, which concludes, "And I will give him the morning star") and the Journey paintings, which refer to the journey of the spirit. He had solo exhibitions in 1943 at the Arts Club of Chicago, the Detroit Institute of the Arts, and the University Gallery, in Minneapolis. Four of his paintings were included in MoMA's Romantic Painting in America exhibition. Other paintings were exhibited at the Phillips Memorial Gallery, in Washington, D.C. He was the rage. Charles Laughton bought seven of his paintings, all of which hung in Laughton's bedroom (Newsweek).

Yet Graves was not happy. It was as if being imprisoned in the army had broken something in his spirit. In a lengthy letter from The Rock to Elizabeth Willis, he wrote, "I feel walled up alone and driven. If it is that I have only practiced a deadening exercise in virtues, then my strong inner structure (which you congratulate me on) is revealed to be not permanently strong but momentarily rigid." And later, "Do you think that I could live alone among the dry rocks and starved willows and not detect the thin cloud of waste pollen drifting?" (Willis papers, 1-7).

Graves v. Tobey

He warned her, "If you need a lover, do not look to Mark [Tobey]. I remember when you touched your chest and spoke of the actuality and urgency of the need -- it may be one that Mark could not fill -- or you for him" (Willis papers, 1-7).

Later, when Tobey proposed marriage to her, Graves wrote to Willis, warning her as a friend that she must absolutely not do it, although he could not tell her the reason (Willis papers, 1-7). It doubtless hinged on his knowledge of Tobey's sexual preference for men -- something it would have been ruinous to Tobey's career to divulge at that time in history. Tobey knew immediately when Willis refused him that Graves was responsible for her change of heart. That, rather than any quarrel over who claimed credit for white writing, may have lain at the heart of bitter feelings between the artists.

In 1945, Graves applied a second time for a Guggenheim Fellowship. He wrote in his application:

“The artists of Asia have spiritually-realized form rather than aesthetically invented imitated form. From them I have learned that art and nature are mind's environment, within which we can detect the essence of man's Being and Purpose, and from which we can draw clues to guide our journey from partial consciousness into full consciousness ... I seek to move away from that Western aesthetic which emphasizes personalized expression of forms without a profound content to support them ... to move away from exhibitionism called self-expression; and toward Eastern art's basis of metaphysical perceptions which produce creative painting as a record ... an outflowing ... of religious experience."

Military Record Foils Fellowship

He was awarded the Guggenheim Fellowship for study in Japan. The award may have helped to offset critic Clement Greenberg's sniffy opinion that year in the British journal Horizon that Graves, whose work he had initially admired, had "turned out to be so narrow as to cease even being interesting."

On his way to Japan, Graves got as far as Honolulu, where he stayed from February to July 1947, studying the Japanese language at the University of Hawaii, painting, (a series based on ancient Chinese ritual bronzes dates from this period, inspired by pieces in the collection of the Honolulu Academy of Art) and trying to obtain a permit to enter Japan, which was under U.S. military occupation.

When permission was denied (probably because of his military record), he returned to Seattle, bringing Hawaiian Japanese painter Yoni Arashiro with him. He used the grant money to build a house on acreage he had bought in 1945, in the forest above Richmond Beach.

Careladen

In a grove of ancient cedar and maple trees, he constructed one of the first homes in the Northwest to be built of cinder block. He designed it with technical help from architect Robert Jorgensen, along the classical lines of French country houses, with 14-foot ceilings. Graves hid it from the world with a high wall. He named the place Careladen. Despite the fact that the name looks Welsh, and he pronounced it "care-LAW-den" and referred to it jokingly as Chateau Careladen, or Chatelet Careladen, old friends say he also meant the name as "care laden," a reference to the length and difficulty and financial burden of the house's construction.

Elizabeth Willis recalls, "When Morris had the dining room built he had a party for me with Mrs. Frederick and Mrs. S. [Stimson] pouring. Mark came to my house that day on purpose with two friends and detained me until we were late, just to offend Morris" (Willis papers, 2-13).

Jan Thompson (1918-2008), who became one of Graves's closest and most enduring friends, describes the occasion on which she first met him as a classic Gothic moment. Richard Gilkey picked her up from her work as a window dresser at the University Book Store. It was snowing. As their car pulled up through stone stanchions Graves had erected at the entry of Careladen, the front door opened, and Graves emerged wearing a full-length black cloak with a hood, carrying a lighted candelabra. The dramatic effect of the cloaked figure, 6 feet, 6 inches tall, emerging into swirling snow, was even more marked when he set the candelabra onto a shelf of a gigantic rock he had brought down from Whidbey Island. "It was like finding myself in a scene from a Russian novel," Thompson said. "It was so beautiful I almost fainted" (Thompson Interview).

His View of the World

Graves lived by the Gothic intuition that no sanity or fulfillment lies in pretending to be an integrated part of humanity. Rather, happiness and survival depend upon remaining isolated, and deploying evasive tactics. On one occasion, he shocked guests at a dinner party by suggesting that money set aside for public art at the airport be spent instead to influence legislation to legalize marijuana. (That predilection may help to explain his later choice of Humboldt County as a place to live, and his almost pathological insistence on barring visitors.)

Despite his occasional antisocial behavior and shock tactics, Graves was a genteel man with highly refined taste, loyal to friends, intolerant of pretension and noise. But he was contemptuous of social expectations. James Washington Jr. recalled that Graves sometimes caused a stir of disapproval when he showed up at art openings with a dead flower in the lapel of his tattered coat, and badly worn-out shoes. "I think he realized that the essence of life lay in simplicity, and he kept testing how far down he could go into that" (Washington Interview).

"He used to go about in a long plaid overcoat that Dorothy Schumacher had mended for him," Leo Kenney recalled. He also recalled that Graves had admired an antique Korean oil jar Kenney had found "among the sad leavings of the Asian internees" who were taken to internment camps in 1942. "He had hands THAT big," Kenney said, "and it was not unknown for him to pocket some beautiful object that took his fancy." Kenney sent word via Gilkey that he would like to trade the Korean oil jar to Graves for "a little scrap of a drawing." On the eve of Kenney's move to California, Graves invited him out for a going-away dinner, and the exchange was made. (Kenney Interview).

The Tide Turns

Too soon, encroaching bulldozers and power saws and planes flying overhead made Careladen intolerable to Graves, as they drowned the subtle sounds of insect orchestras, bird chatter, and the brush of trees each against each. He recorded his frustration in a series of Machine Age Noise paintings. His frustration can be readily understood by anyone who has had a construction project as a neighbor. The noise drove him away from the place: "The roads that have been smashed through a woods in a day -- a single day! -- with bulldozers ... and the houses (flashy shacks) that are being built in a day along these roads (within earshot of Careladen) breaks my heart. HELL is here and now in all its Dante-terror" (Graves to Willard, February 12, 1952).

To add to his woes, by 1948, New York critics had begun to take a cool view of his work. Sam Hunter said of his symbols, "Their intensity seems precious and one of surfaces. The effect is more one of autohypnotic hallucination than metaphysical revelation" (Hunter).

Another reviewer, who signed himself A.B.L., complained of the pretentiousness of Graves's paintings mounted as hanging scrolls, "especially the phony ‘seal' on one." Robert Coates wrote, in The New Yorker, "Despite his amazing virtuosity one feels that underneath the surface charm there is only emptiness, or at most, a thin, vaporous mysticism" (Coates).

Graves Gets Out of Town

Graves traveled to England in the fall of 1949 as a first class passenger on the Mauritania, the guest of British art collector Edward James (said to have been the illegitimate son of Edward VII). James wanted to commission Graves to paint murals in lunettes at his mansion at West Dean Park. Portrait painter Carlyle Brown, a guest along with Graves, painted a portrait of Graves. Graves stayed with James in England for more than a month, and in the end turned down the commission.

He traveled on to France; his destination was Chartres, where he arrived on September 2, 1949. He rented three rooms in part of a building that had been a seventeenth-century abbot's residence, for the equivalent of $30 a month. He spent three winter months there in near solitude.

Poet Kenneth Rexroth has recorded that Graves painted at Chartres Cathedral every day, taking in details, fragments of statues, bits of lichened masonry, and making several pictures of the interior of the cathedral in the early morning, with the great vault half filled with thick fog, and dawn beginning to sparkle in the windows. It is not improbable that in the cathedral's great circular stained glass windows, Graves found resonance with the mandalas of Buddhist tanka paintings. He regarded the cathedral as "a great diagram of how to enter heaven, but to enter requires tremendous skill, and this I must acquire through the act of painting" (Harper's Bazaar).

Brassai, the noted French photographer, captured Graves's portrait one day at Chartres. Cigarette in hand, with a tousle of uncombed dark hair and an ample black beard, he gazes at the camera with an air of consternation, looking like nothing so much as a hollow-eyed political prisoner. A sheepskin vest over a worn sweater protects him from the cathedral's dank chill. Behind his head, a partially completed painting is visible, showing the chalky outline of a short, wide-rimmed vase, whose opening is tipped sharply toward the viewer. A closed white bud droops to the right, while a few other flowers have begun to take shape against the rim.

It is the only record extant of his paintings that winter, and it bears no resemblance to the subjects mentioned by Rexroth. Later, in Seattle, deeply dissatisfied with his work, he destroyed nearly everything he had painted at Chartres. Elizabeth Willis, who saw the body of work before Graves destroyed it, wrote, "I vaguely remember that the work was sort of hard drawings and a few paintings of gargoyles; in fact nothing that I wanted him to show to anyone." She recalled that after Graves came back from Chartres, "He was never the same again. All the old and beautiful sensitivity had faded, the Inner Eyes, the consciousness, all that was gone" (Willis papers). Others close to Graves disagree with this assessment.

Graves returned to Seattle in 1950 with tastes for possessions that he had not had before, and with a desperate need for money to fund the ongoing work on Careladen. Willis, on whom he had relied for sales in both Seattle and New York, had become acting assistant director at the California Palace of the Legion of Honor, in San Francisco. She continued to sell work by both Graves and Tobey, but rarely produced enough money to satisfy Graves.

Practicing Voodoo

In December, infuriated that Dr. Fuller was stalling about buying a couple of paintings he had offered, Graves wrote to her jubilantly:

"I made a little likeness of [Dick Fuller] out of mud, and thrust long cedar splinters through it and stomped & stomped & stomped on it & then threw it into the stove. Next day the paper said Dr. F. was jailed for drunken driving, and the next day it said Dr. F. refused bail, and the next day it said his house had caught on fire and burned the telephone wires so he couldn't call the fire department .... I'll wait until he's out of jail. Then if he wants to go ahead and buy the two paintings, I'll send him a note of acceptance & also tell him that I'll leave his mother alone too! All this about Dick Fuller is true" (Willis Papers, 1-3).

"Morris used to get sick rages when no one would buy his paintings," Willis said (Willis papers, 5-14). But, if he was sometimes childish and petty, he could also take the high ground. In 1950, he wrote a much-quoted letter to Melvin Kohler, then associate director of the Henry Art Gallery. It said, in part:

"There are three 'spaces': Phenomenal Space (the world of nature, of phenomena), the space outside of us; Mental Space, the space within which dreams occur and the images of the imagination take shape; Space of Consciousness, the space within which is revealed (made visible upon subtle levels of the mind) the abstract principles of the Origin, operation, and ultimate experience of consciousness.It is from this Space of Consciousness that comes the universally significant images and symbols of the greatest of religious works of art. The observer can readily see from which 'space' an artist has taken his ideas and forms .... The majority of artists along with the majority of laymen have either no inclination to understand their own ability to segregate these "spaces' and be informed by them, or they 'enjoy the confusion and unintelligibility which results from blindly mixing these three spaces.

The value of enjoying the arts is that the energy channeled into the esthetic emotions refines and sensitizes the mind so that it can more skillfully seek and more readily grasp, an understanding of the Origin of Consciousness. In great religious works of art, the unique value of the revealed images and symbols is that they become supports for the mind of the person who is seeking knowledge of the cause (and ultimate goal) of this mad-sublime dance we call LIFE. Secular and scientific 'art' is concerned with evolution. Religious art is concerned with involution" (Graves to Melvin Kohler).

Graves's Sense of Humor

Museum officials, collectors, and art world notables all expressed a desire to see Careladen as its construction progressed. It led Graves, in the spring of 1953, to stage the first Northwest art "happening," although that word still lay several years in the future.

The event was born during an outdoor dinner at Careladen. Jan Thompson, Gilkey, Ward Corley, and Dorothy Schumacher dined with Graves and his longtime companion, Richard Svare, at a table laid with white linen and set with silver in the portico. Svare and Schumacher cooked a feast, complete with a roast turkey. After-dinner conversation turned to art competitions, and entry fees, and the conservative standards of the judges. The banquet table with the remains of the feast was in itself a work of art, they perceived. With the kind of tipsy high spirits familiar to many who have enjoyed a fine dinner and an evening of good conversation, they decided to make an art exhibition of the table.

They sent invitations to people on the Seattle Art Museuem mailing list, (which they obtained without Dr. Fuller's knowledge or consent) saying, "You or your friends are not invited to the exhibition of Bouquet and Marsh paintings by the 8 best painters in the Northwest [The eight included Graves's friends and neighbors Clayton and Barbara James, without their knowledge] to be held on the afternoon and evening of the longest day of the year, the first day of summer, June 21, at Morris Graves' palace in exclusive Woodway Park. Refreshments will be served" (Invitation in the collection of Clayton and Barbara James).

They left the remains of their dinner intact, complete with tipped cups and wine stains. Gilkey attached a sprinkler head to the center of the roof of the gatehouse, blocking entry with the table. Most of those who received "You Are Not Invited" cards preferred to think Graves had employed coy wording, and that they were, indeed, invited to Careladen. Most responded to what they perceived as a formal invitation by dressing formally for the occasion.

A trench dug across the dirt road leading to the house obliged people to leave their cars and walk up the approach. They arrived to find lights illuminating the withered flowers and moldy remains of a feast that the spray from the sprinkler had slowly dribbled down on for ten days and nights. Dorothy Schumacher provided dinner music interspersed with a recorded pig fight.

With no way through the gate, most of the guests left in disgust and outrage. Helmi Juvonen, ever open to wonder, exclaimed, "Oh, how wonderful!" and sat down to sketch the scene. Leon Applebaum, Thompson recalls, was particularly furious. He grabbed a silver pitcher from the table, and took it along when he departed.

Graves observed it all through a chink in the cinder-block wall that abutted the gatehouse, along with Svare, Gilkey, Thompson, Corley, and Schumacher -- his guests from the dinner. "It went on for hours," Thompson said. "It was mildly terrifying, and so funny that I wet my pants." A photographer for Life magazine showed up to shoot photos of the table. Graves, who had not responded to outcries that he show himself, finally emerged from hiding to forbid further pictures.

The principal casualty of the evening was Graves's friendship with Clayton and Barbara James, whose names he had added to the invitation without consulting them. They were not amused. In addition to having dug a trench cross the access road, he had put coiled barbed wire on the ground between his place and the James's house. They were so offended that they put a painting he had given them inside the barbed wire and severed their friendship.

As Thompson recalls, Graves's motivation for the event was in part frustration at the absence of drama in the art world. Everyone and everything operated on a level of politeness he found stultifying. Entertainment took the form of "little teas."

That September, Life magazine carried a feature article titled "Mystic Painters of the Northwest," with Graves described as the most important of the four artists (Morris Graves, Guy Anderson, Kenneth Callahan, and Mark Tobey) pictured in color. It cemented Graves's place as an artist of national note.

Elizabeth Willis noted in her journal:

"When he became famous [Morris] lost all need for his beloved role as exhibitionist. The poverty-struck saint was also out of order. Further than that was the deadly, deadly fear that he could not create — knowing that his way of life had finally murdered the beautiful innocent generous child within him — the child who identified himself with absolute directness to every aspect of nature" (Willis papers, 1-2).

In the fall of 1954, Graves spent five weeks in Japan to assemble a collection of rice paper and compatible paste for future paintings that he hoped would carry the spirit of traditional Japanese art. He studied paper mounting techniques used for scrolls, and attended performances of Noh theater. The dramatic Noh masks inspired a series of Masked Bird paintings.

A Home in Ireland

Svare and Schumacher had gone to Ireland to find a place for the three of them to live. (Dorothy Schumacher returned to the United States in 1956, by Svare's account.) Svare recalls:

"We first lived in southwest County Cork on an estate called Innish Beg, the former home of Kathleen MacCarthy-Morrough — the chauffeuse of General Eisenhower during World War II. We paid $65 a month. We had a pet goose and a pet goat there. After two years, we moved to County Waterford, where we lived in the groom's house of an estate for several months, and finally to Dublin, first in an 18th century house on Fitzwilliam Square, and ultimately to Woodtown Manor" (Svare Interview).

Graves told an interviewer that he lived in Ireland because the landscape and climate reminded him of the Washington coast. "I have memorized the Northwest so I can use it. When I am away I can use it as much as I wish. It does not crowd me like a new environment. I have it in memory" (Soby, 34).

In 1956, Graves included some of the paintings he had done in Ireland in a retrospective exhibition that opened at the Whitney Museum, in New York, and traveled to the Phillips Gallery, in Washington D.C.; the Museum of Fine Arts, in Boston; the Des Moines Art Center; the M. H. de Young Museum, in San Francisco; and the Art Galleries of U.C.L.A. The critics were not kind. James Thrall Soby, wrote in the Saturday Review of Literature: "The recent large oils are to my mind far inferior to his earlier work in tempera, being rather cold, swollen and dry and lacking the confessional intensity of the smaller pictures" (Soby, 34).

Graves sold Careladen in October 1957. He and Svare had Thanksgiving dinner with the Duke and Duchess of Windsor at their estate near Paris. Graves had met them earlier that year when he became the first and only recipient of the Windsor Award.

Woodtown Manor

In September 1958, he used proceeds from the sale of Careladen to buy Woodtown Manor, an eighteenth-century Georgian house in the countryside near Dublin. He and Svare spent a year rebuilding and repairing the house and landscaping the grounds. During that time, Graves was not painting. "We completely restored this plain, beautiful house on the hills above Dublin and just below the ruins of the infamous eighteenth-century Hellfire Club," Svare says (Svare Interview). They covered the eighteenth-century damask of their chairs with beige linen, and brought in seedlings of chestnut trees from the gardens of the French Palace of Versailles for the garden.

In Ireland, Graves painted a Hibernation series and a group of fantasy, little-folk creatures in Hedgerow and Irish Fauna series, most done during the period he lived in County Cork.

Friends say Graves spent hours looking through a telescope at the night sky from Woodtown Manor. He was distressed that the lights of Dublin, five miles distant, were visible at night. He spent much of 1960 developing a body of sculpture that would seem to have been inspired by his observations of the night sky and news about U.S. space exploration. He exhibited the pieces as Instruments for a New Navigation.

Constructed of cast bronze, glass, and stone, they were a world away from misty birds. Totemic circles of glass or pale stone were balanced on slender rods above solid stone bases. Many of the discs were perforated with a central "lens," suggesting something to be sighted through. They perched on stone pedestals at a time when avant-garde sculptors were eliminating the pedestal from sculpture. One reviewer noted, "There is a strong whiff of the 19th century about these objects" (Schwabsky). Graves's audience was not ready to receive them. Disassembled for storage, they were not reassembled until 1999, when they were exhibited at the Schmidt-Bingham Gallery in New York.

When Graves sold Woodtown Manor in 1964, he destroyed much of the work he had done in Ireland before returning to Seattle. He lived briefly on the main floor of the Capitol Hill house owned by Guendolen Plestcheeff. She occupied the second-floor "penthouse," originally constructed as a ballroom. (Guendolen Plestcheeff left the house to the Seattle Art Museum for use as a Decorative Arts Center.)

California Beckons

His stay in the Northwest was brief. Later that year, he bought property in Loleta, some seventeen miles south of Eureka, in northern California. He told Wesley Wehr:

"When I was very young, I drove through this area with my family. I remember looking out the car window at this landscape and telling myself, 'Someday I'm going to live here.' Several years ago I learned that there was some property here with a private lake, and surrounded by virgin redwood trees. The woman who owned the property, I was told, would not consider selling any of it to anyone. Then she heard somehow that it was I who wanted to buy her property to live on. She had heard of me, and she said I would, as an artist, respect the pristine beauty of her property and take good care of it" (Wesley Wehr, unpublished notes).

He built a house off a dirt road through a gate, past a farmhouse, through a second gate, down a narrow dirt road through a forest. The secluded new house was designed by Seattle architect Ibsen Nelsen.

The Shift Toward Incandescence

The move marked a dramatic shift in Graves's paintings. No longer was any metaphysical intuition implied in his images. Gone were the black and gray washes. In their place, he produced still life paintings that glowed with incandescent yellows, and rosy pinks, and deep, jewel-like carmine.

Against chalky, fading surfaces reminiscent of aged fresco, he set small, intimate objects: a bottle or two of wildflowers and perhaps a bowl of plums, so placed as to suggest that each is an individual treasure, an icon. A line of single blossoms, each in its own simple container, radiated a sense of "beingness" that is little short of reverential. As still lifes, they were profoundly still. The subjects seem to be not flowers or fruit, but light.

They are painted so delicately that the pigment seems breathed into place. Graves projected intensity into them by rendering the images veiled and shimmering, suggesting not only the fleeting life of blossoms, but the evanescence of life itself.

Coming Full Circle

The still life paintings came at a point in Graves's life when he was no longer interested in embedding a message in his paintings. "My first interest is Being -- along the way I am a painter," he said. "As a painter I am aware of the ‘Sky of the Mind' " ("Morris Graves: Vessels of Transformation, 1932-1986") In returning to wildflowers, Graves had come full circle from his childhood. But this time, he conveyed a heightened awareness of Beauty as an absolute concept.

In 1979, he returned to the theme of birds, rendering Spirit Bird and Moon Bird centered in chalky tondos. He also produced what is perhaps his most beautiful bird painting ever, the tripartite Waking, Walking, Singing in the Next Dimension. Three birds are enclosed in sumi-style circular sweeps of white, their bodies translucent against a softly glowing rainbow ground.

Although many artists have put form to states of mind, it is difficult to think of another painter as involved as Graves was for most of his career in symbolic representations of consciousness. For him, consciousness often assumed the form of a bird, or of a chalice -- a form of the Holy Grail, a time-honored symbol of the search for truth and redemption.

No small part of Graves's talent lay in the matter of titling his paintings. Attach a mundane title such as Spring Study to the painting Graves titled Bird Maddened by Machine Age Noise, or Crane to Conscious Assuming the Form of a Crane, and you diminish it by half. Art critic Mark Daniel Cohen called Graves's title The Opposite of Life Is Not Death; The Opposite of Life Is Time, 1962/99 "the best title for a work of visual art I have encountered" (Cohen).

No discussion of Graves would be complete without mention of the time and extraordinary energy he devoted to creating aesthetic living environments, especially with limited means. Always unique, rarefied well beyond the usual constraints of low income, they were exemplary havens of beauty and serenity. Known only to his intimate friends, the succession of his homes -- The Rock, Careladen, Woodtown Manor in Ireland, and The Lake in Loleta -- are his least-known and most unsung works of art.

In a recent accolade, in January 2000, the Humboldt Arts Council rededicated Eureka's old Carnegie Library as the Morris Graves Museum of Art. It would have been fitting for a Graves Museum to be sited in the Northwest, near Seattle. But, like the abortive plans for a Mark Tobey Museum, it was not to be.

Graves died peacefully at home May 5, 2001, a few hours after suffering a stroke. His longtime companion Robert Yarber reported that at the moment of Graves's death, a heron cried out from the lake outside his window. Just 19 days later, The Rock burned. The fire happened so soon after his death that friends say he was hurling thunderbolts.