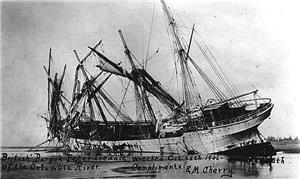

The stretch of coast between Tillamook Bay in Oregon and Vancouver Island, encompassing the mouth of the Columbia River and the entrance to the Strait of Juan de Fuca, has claimed since 1800 more than 2,000 vessels and perhaps as many as 1,000 lives. At the Columbia, the combination of river flow and offshore currents created an ever-shifting sand bar at the mouth, which in itself represented a hazardous crossing. But fogs and violent weather systems from the North Pacific or sometimes just bad luck caused ships to founder or burn or to be crushed against the shore. Beginning with the California Gold Rush, when sailing ships and steamers transported lumber to California, mariners called the area the Graveyard of the Pacific. Light houses, light ships, buoys, and audible and electronic beacons helped mariners find the entrance to the Columbia while improvements to navigation in the form of jetties and a dredged channel eliminated major disasters after the 1920s. Still, the sea continues to claim lives every year.

The Great River

The 1,214-mile-long Columbia drained an area the size of France and discharged between 90,000 and one million cubic feet per second of water into the Pacific, depending on the season. The rocky shores of the Columbia's mouth funneled the river into the ocean with great force, something like a firehose, unlike other major rivers whose power dissipates in deltas.

As the Columbia met the sea, sand and silt entrained in the current dropped to the bottom to form a shallow bar. The Pacific Ocean met this flow and the bottom with the Japan Current creating massive breakers. Native Americans did not try to confront these forces and generally made their livings inland or launched their sea-going canoes from beaches away from the river's mouth.

The Treachery of the Bar

It was Europeans and Americans in search of the River of the West who discovered the treachery of the bar. Native oral tradition mentions encounters with what were undoubtedly Europeans or Asians whose ships washed up on beaches as early as 1700. In 1775, Spaniard Bruno Heceta first mapped the entrance to the Columbia, but illness among his crew precluded any attempt to probe further. It fell to American trader Robert Gray (1755-1806) to cross the bar in May 1792 in his Columbia Rediviva, which gave the river its name.

H.M.S. Chatham, an armed tender of the Royal Navy, nearly became the first recorded victim of the Graveyard of the Pacific. Lieutenant William Broughton (1762-1821) had been dispatched by Captain George Vancouver (1758-1798) to follow up on Captain Gray's report of a great river. Broughton explored the Columbia. On her way out of the river, Chatham ran aground on what would be called Peacock Spit on the north side of the mouth. Broughton brought his ship off the sand, successfully avoiding loss of his command.

Death at Sea

As traders exploited the fur resources of the interior at the turn of the nineteenth century, they had to weather the currents, breakers, and shifting channels of the mouth. In 1798, the brigantine Hazard dispatched a small boat to take soundings, and five men died. The British bark William and Ann, bearing supplies for the Hudson's Bay Company's Fort Vancouver, wrecked on Clatsop Spit in 1829 and 29 lost their lives.

The U.S. Exploring Expedition's U.S.S. Peacock broke up on the sand spit on the north side of the mouth in 1841 and gave its name to the spit. Peacock's captain left the ship's launch at Fort George nearby to be used by local residents as a rescue boat in the event of other ships in distress.

The Graveyard and its Guides

In 1849, the California Gold Rush proved an economic boon to the sparsely settled Northwest. Mining operations and the booming (and frequently burning) city of San Francisco demanded as much cut lumber as the settlers of the Oregon Territory could produce. Seaborne commerce increased and so did the accidents, three in 1849 alone. The year 1852 chalked up five wrecks, as did 1853. The biggest problem was the shifting bar. What had been a safe channel earlier in the season might invite grounding and disaster only months later. It was during these years that mariners dubbed the mouth the "Graveyard of the Pacific" (Gibbs, 28).

Familiarity with the bar was critical to a safe crossing and experienced mariners established themselves in Astoria as bar pilots. They would sail (and later steam) out beyond the breakers and wait to guide arrivals with their pilot boats across the bar for a fee. The Columbia Bar pilots became important -- and affluent -- members of the local community.

As the Northwest economy grew so did shipping traffic. Lumber, grain, and coal were big exports and all needed ships. Tides and winds could carry ships up and down the Columbia as far as the Cascades, but Portland became the big city of the Northwest. Schooners and other sailing vessels carrying coal, lumber, and later grain from Portland's rival, Seattle, on Puget Sound, had to weather Cape Flattery. Swift schooners with fresh oysters from Shoalwater Bay had to pass an entrance only a little less treacherous than the Columbia.

Help Is On the Way

The U.S. government established lights at Cape Disappointment (1856), Cape Flattery (1857), and Shoalwater Bay (1858), which at least gave mariners a reference point. Storms still drove ships onto the rocks and sand. More lights went in along the coast into the twentieth century and light-ships anchored out from the coast beginning in 1898. Buoys marked the channels.

The rescue of shipwreck victims fell to volunteers who risked their lives to bring off passengers and crew, but the locals were also happy to salvage the wrecks and the cargo for their own profit. The U.S. Lifesaving Service established stations manned by trained professionals beginning in 1877 at North Cove on Shoalwater (Willapa) Bay and at Fort Canby on Cape Disappointment the following year. Finally professionals rowed out to attempt rescues, but most parts of the coast were simply beyond the arms and backs of the lifeboat crews.

Building a Jetty

Portland businessmen petitioned Congress in the early 1880s to do more about the hazards of the mouth of the Columbia. Congress appropriated funds for a jetty to extend out from Clatsop Spit on the south side of the mouth to be built by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, responsible for maintaining the nation's waterways. The engineers built a wood railroad trestle out into the ocean from which dump cars discharged boulders.

By 1894 (with some breaks in activity to secure more funding) the jetty was five miles long. This kept sand from building up in the channel to a certain extent, but only with two more miles of jetty completed in 1914 and a north jetty completed in 1925 was the shifting nature of the bar stabilized. Even so, to this day the Corps of Engineers has to dredge the channel to accommodate larger ships.

Calamity at Sea

The turn of the twentieth century saw a very high number of wrecks by sailing ships, 25 between 1890 and 1910. Historian James Gibbs repeats speculation that the demise of the sailing ship may have tempted owners to cynically wreck their unprofitable bottoms despite the loss of dozens of lives.

Although the Columbia took most of the maritime victims, Cape Flattery at Washington's northwest tip and its opposite number, Pachena Point, a headland located just south of Bamfield on Vancouver Island’s west coast, have claimed their share of victims. Although lacking a river bar, the Strait of Juan de Fuca can boast weather to equal the Columbia's. As an example of what sailing ships dealt with in 1912, the British bark Endora made it to Cape Flattery from Honolulu in 18 days, but it took another 24 days and seven tries to get past the Cape and into Puget Sound.

Some of the other significant disasters of the Graveyard of the Pacific (not including acts of war) in terms of loss of life include the following:

On March 22, 1811, eight men from the 10-gun brig Tonquin serving John Jacob Astor's North West Company drowned when their captain ordered them into a defective whale boat to take soundings of the mouth of the Columbia. The passengers of the Tonquin founded Astoria in what would become Oregon. (The Tonquin was later lost in a conflict with Indians on Vancouver Island.)

On March 10, 1829, the British bark William and Ann wrecked on Clatsop Spit. Either 46 or 26 persons lost their lives.

On January 28, 1852, one of the first steamers to work the Pacific coast, the sidewheeler General Warren, enroute to San Francisco from Portland, got into trouble off Clatsop Spit. The captain ran the ship aground and dispatched 10 men in one of the remaining ship's boats to row to Astoria for help. When rescuers returned all they found was wreckage. Forty two died in the surf including a newly married couple found on the beach, their hands still clasped. Two years later, the entire stern frame washed ashore 60 miles north of Clatsop, demonstrating the power of the currents.

On November 20, 1852, the schooner Machigone, left Astoria for San Francisco with a cargo of lumber and a crew of nine. Shortly thereafter a heavy gale lashed the coast. She was never heard from again.

On November 29, 1852, the brig Marie crashed into the shore two miles north of Cape Disappointment. Nine men including the captain died and two men barely survived.

On January 9, 1853, the bark Vandalia struck Cape Disappointment and nine died.

On December 21, 1859, the schooner Rambler washed up on Clatsop Spit with just her bottom showing. She was out of Neah Bay for San Francisco with peltries (undressed pelts) and oil after trading with Indians to the north. No trace of the crew of four was ever found.

On December 27, 1860, the bark Leonese washed up on Clatsop Spit upside down. No trace of the crew of nine was ever found.

On March 15, 1865, the bark Industry out of San Francisco followed a pilot boat across the Columbia bar, but when the wind failed, the sailing ship struck bottom in the middle sands. There followed a desperate effort on the part of the crew and soldiers from Fort Canby to rescue those on board. Still, 17 people out of 24 died.

In January 1869, the schooner Anna C. Anderson left Oysterville on Shoalwater Bay with a cargo of fresh oysters for San Francisco. The ship perished with all seven on board.

On November 4, 1875, the sidewheeler Pacific left Victoria, B.C. and rounded Cape Flattery en route to San Francisco that night. In the darkness, the sailing ship Orpheus out of San Francisco in ballast struck the Pacific, which sunk almost immediately. Out of more than 250 passengers and crew, one man, the quartermaster, survived.

On November 22, 1875, the schooner Sunshine washed up on Long Beach peninsula keel up. No trace of the 25 people on board was ever found.

In 1876, the sloop Dreadnought wrecked on Clatsop Beach with the loss of all seven hands.

On April 18, 1879, the sidewheeler Great Republic was the largest passenger liner on the Pacific Coast. She became stranded on Sand Island in the mouth of the Columbia. The passengers and most of the crew -- more than 1,000 persons -- successfully evacuated, but the last lifeboat overturned the next morning and 11 crewmen drowned.

On May 4, 1880, several hundred local fishermen drowned when they were caught by gale winds and were unable to row ashore against the flow of the river. Contemporary accounts give losses of anywhere from 60 to 350 dead.

On January 3, 1881, the British bark Lupatia ran aground and foundered off Tillamook Head. Sixteen men died, but the ship's dog survived.

On October 7, 1883, the schooner J.C. Cousins was a luxury yacht operated by the State of Oregon as a pilot boat out of Astoria. The crew had laid in provisions and moved off Clatsop Spit to await ships needing to be guided across the bar. A change of wind sent her towards the spit, but she failed to come about and was driven hard onto the beach. When rescuers reached the wreck at low tide they found the ship's boat, the log and papers, and the entire crew of four missing. This led to speculation of murder and mutiny, but the mystery of why she beached and what happened to the crew was never solved.

On October 24, 1888, the barkentine Makah, washed up on Tillamook Head capsized. She had been en route from Port Discovery, Washington, to Sydney, Australia, with lumber. No sign of the crew of 11 was ever found.

On January 4, 1890, the schooner Dearborn was discovered, capsized but afloat off the mouth of the Columbia. No trace of her crew was ever found.

On November 3, 1891, the British bark Strathblane out of Honolulu struck the beach south of Ocean Park. While hundreds watched, rescuers tried to help but the ship broke up in the heavy surf. Seven died.

On October 3, 1893, gales blew the Chilean bark Leonore ashore at the mouth of the Quillayute River south of Cape Flattery. Five men and one woman died.

On January 1, 1900, the steam schooner Protection out of Seattle with a cargo of lumber for San Francisco sank in a storm with the loss of all hands.

On December 11, 1900, the British bark Andrada disappeared off the mouth of the Columbia and was believed to have foundered off the Washington coast with all hands.

On January 16, 1901, the British bark Cape Wrath en route from Peru to Portland was sighted off the mouth of the Columbia, but neither she nor her 15 crew members were ever seen again.

On January 8, 1904, the steamer Clallam out of Seattle for Victoria by way of Port Townsend foundered off Victoria harbor and 56 people, mostly women and children, died.

On January 22, 1906, the steamer Valencia out of San Francisco for Seattle crashes into Pachena Point on Vancouver Island while trying to make the Strait of Juan de Fuca. One hundred and thirty-six persons die.

In December 1909, the schooner Susie M. Plummer out of Everett for San Pedro with a cargo of lumber was discovered off Cape Flattery abandoned by her 12-man crew. Only her cargo kept her afloat until she washed ashore into San Josef Bay weeks later. No trace of her crew was ever found.

On February 13, 1911, the motor vessel Oshkosh out of Tillamook for the Umpqua River struck bottom off the south jetty and began to take on water. The captain tried to take the ship into the river, but it capsized, killing six of the seven men on board.

On January 7, 1913, the captain of the tanker Rosecrans mistook the North Head Light for the lightship and crashed into Peacock Spit and sank. Rescuers found four men clinging to the rigging, all that was left above water. Only three could be saved. Even then, the rescue boat from Point Adams had to find safety at sea with the lightship. Thirty-two people died.

On September 18, 1914, the steamship Francis H. Leggett out of Grays Harbor for San Francisco foundered 60 miles southwest of the Columbia. Sixty-five died and only two people survived.

On February 28, 1918, the schooner Americana cleared the Columbia bar with a cargo of lumber en route to Australia. No trace of her or her 11 crew was ever found.

On the foggy night of May 28, 1922, the freighter Iowan struck the British steamer Welsh Prince inside the entrance to the Columbia off Altoona Head. Seven seamen died in the fo'c'sle of the Welsh Prince and the vessel sank to the bottom of the river.

On July 26, 1934, the battleship U.S.S. Arizona collided with a purse seiner off Cape Flattery at night in calm seas and in good visibility. Two fishermen died.

On January 12, 1936, the freighter Iowa crossed the bar with lumber and general cargo into a 76-mile-an-hour gale and was swept onto Peacock Spit. By the time the Coast Guard Cutter Onondaga reached the wreck, all that was visible were the tops of the masts. Thirty-four died.

On December 20, 1951, the Danish cargo-liner Erria caught fire while at anchor off Tongue Point near Astoria. As crew members struggled to evacuate passengers, Coast Guardsmen and civilians from Astoria went to the rescue in boats. Three crew and eight passengers were trapped and died, but 103 were saved. The cargo was salvaged and the ship was eventually repaired.

On January 14, 1961, the fishing boat Mermaid lost her rudder and radioed for help. Three Coast Guard units responded from Cape Disappointment and Point Adams. The towline from the motor lifeboat Triumph to the Mermaid parted and when Triumph came about, she flipped over. Another 40-foot cutter rolled going to Triumph's aid. The crew of the 36-foot cutter managed to rescue three Coast Guardsmen, but could not help the fishermen. Three fishermen and four Coast Guardsmen died.