Dance Marathons (also called Walkathons), an American phenomenon of the 1920s and 1930s, were human endurance contests in which couples danced almost non-stop for hundreds of hours (as long as a month or two), competing for prize money. Dance marathons originated as part of an early-1920s, giddy, jazz-age fad for human endurance competitions such as flagpole sitting and six-day bicycle races. Dance marathons persisted throughout the 1930s as partially staged performance events, mirroring the marathon of desperation Americans endured during the Great Depression. In these dance endurance contests, a mix of local hopefuls and seasoned professional marathoners danced, walked, shuffled, sprinted, and sometimes cracked under the pressure and exhaustion of round-the-clock motion. A 25-cent admission price entitled audience members to watch as long as they pleased. Dance marathons were held in Spokane, Seattle, Yakima, Wenatchee, Bellingham, and elsewhere. They occupied a slightly disrespectable niche in society, and many towns banned them, finding them disruptive, disturbing, and even repugnant.

Callus Carnivals

Dance marathons were known as "bunion derbies," and "corn and callus carnivals." Promoters called them "walkathons." Social dancing had only recently acquired a veneer of respectability through the efforts of wholesome married dance teams like Vernon and Irene Castle. At a time when many churches still considered dancing sinful, "walkathon" was a less threatening term. But today we remember these endurance contests of the Great Depression as "dance marathons."

Dance marathons were both genuine endurance contests and staged performance events. Professional marathoners (often pretending to be amateurs) mixed with authentic hopeful amateurs under the direction of floor judges, an emcee, and the merciless movement of the clock to shape participatory theater. Both grim spectacle and vaudeville-based amusement, dance marathons offered an inexpensive chance for audiences “to be entertained and while away time” (Calabria, p. 21). They also offered audiences the Depression-era novelty of feeling superior (and feeling pity) toward someone else.

Virgin Towns

Top contestants vied for the chance to win hundreds or (rarely) thousands of dollars, but promoters of a successful dance marathon walked away with much more. Promoters sought "virgin spots" -- towns where a marathon had not yet been staged. Novelty (and prodigious advertising) was required to draw large crowds. Virgin towns also had the advantage of a citizenry unburned by dishonest promoters who skipped town without paying their bills. Promoters tried to arrange local sponsors such as the Veterans of Foreign Wars or the American Legion in order to enhance respectability.

Despite their controversial status, during the 1930s dance marathons were entrenched in American culture. Dance marathon historian Carol Martin reports that nearly every American city of 50,000 people or more hosted at least one endurance dance marathon. Washington was no exception: Contests were held in Spokane, Seattle, unincorporated King County, Bellingham, Spanaway, Wenatchee, Fife, Vancouver, Yakima, and probably in other towns as well.

Desperately Entertaining

Seattle passed an ordinance prohibiting dance marathons within city limits on September 5, 1928. This ordinance was prompted by the attempted suicide of a Seattle woman who had competed in a 19-day marathon held in the Seattle Armory, and placed only fifth. Bellingham passed a similar ordinance on January 26, 1931, and Tacoma passed one on June 10, 1931. On March 13, 1937, the state of Washington passed an act prohibiting dance endurance contests statewide.

In 1934 when the American Social Hygiene Association asked police chiefs across the nation about their municipalities’ laws regulating endurance dance contests, the replies showed "deep antipathy" (Martin, p.130) toward the marathons.

Opponents to dance endurance events included movie theater owners, who lost money when their patrons attended a marathon instead of a movie. Churches and women’s groups objected on both moral grounds (the contestants’ dance positions resembled dragging full-body hugging rather than social dance positions) and for humanitarian reasons (it was wrong to charge money for the dubious privilege of watching bedraggled contestants become increasingly degraded). The police found that marathons attracted an undesirable element to their towns. Certainly the marathon promoters and professional dancers (who almost invariably collected the prize money) were transient and invested only in short-term gain.

This gain was cumulative for those to whom it befell: “In their heyday, dance marathons were among America’s most widely attended and controversial forms of live entertainment. The business employed an estimated 20,000 people as promoters, masters of ceremonies, floor judges, trainers, nurses and contestants” (Martin, p. xvi). Within Washington communities where dance marathons took place, advertising dollars went to newspapers and radio stations. Venues were rented and license fees paid. Local sponsors gained attention for their businesses. Food concessions for both spectators and contestants also brought money into local coffers.

Dance marathons opened with as great a fanfare as the promoter’s press agents could muster. Each major promoter had a stable of dancers (known as horses, since they could last the distance) he could count on to carry his event. These professionals (often out-of-work vaudevillians who could sing and banter and thus provide the evening entertainment that was a feature of most marathons) traveled at the promoter’s expense and were "in" on the performative nature of the contests (including the fact that the outcomes were usually manipulated or at least loosely fixed).

Food, a Roof, and Hope

Known euphemistically as “experienced couples” (The Billboard, April 14, 1934, p. 43), professionals did their best to blend in with the hopeful (often desperate) amateurs. For all contestants, participation in a dance marathon meant a roof over their heads and plentiful food, both scarce during the 1930s. President Herbert Hoover's promised prosperity "just around the corner" eluded most Americans, but dance marathon contestants hung their hopes on the prize money lurking at the end of the contest's final grind.

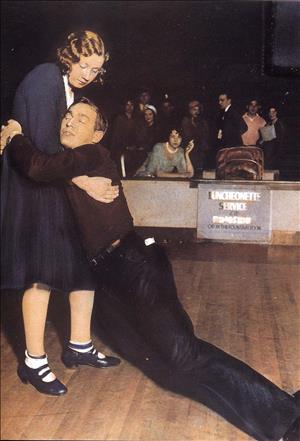

Contestants, who danced in pairs, were required to remain in motion (picking up one foot, then the other) 45 minutes each hour, around the clock. Dancing was often loosely interpreted to include shuffling along while shaving with a special mirror hung around the female partner’s neck, writing letters on a special folding desk hung around one’s own neck, reading the newspaper, knitting, or even sleeping as one’s partner supported one’s weight. The "carrier" in such a couple often tied the "lugging" partner’s wrists together with a handkerchief and hooked them around the carrier’s neck for additional security. Women carried their sleeping male partners, despite the inequality of height and weight. “It was the women who kept up and mostly men who faltered” (Broun).

The rules during this "walking act" portion of the marathon were that feet keep moving up and down and that contestants’ knees never touch the floor. Knees touching the floor brought immediate disqualification. To encourage lagging couples to continue moving, the floor judge sometimes used a ruler to flick the legs of contestants who were not shuffling with sufficient alacrity. In extreme cases partners were fastened together with dog chains to prevent them from drifting apart.

How Long Can They Last?

Contestants who learned to adjust to this around-the-clock motion danced on as the sign above them ticked up the hours and ticked down the number of contestants remaining. Always, written on placards surrounding the dance floor and endlessly repeated by the marathon emcee was the question: “Ladies and Gentlemen, How Long Can They Last?”

Contestants were expected to dance full-out during the heavily attended evening hours. A live band played at night, whereas a phonograph often sufficed during the day. The longer the marathon wore on, the more endurance events the contestants found themselves subjected to. Sprint races, long periods without medical care, removal of rest periods, along with the more common shin splints, bunions, blisters, and fallen arches soon whittled down the number of participants.

Special endurance events were heavily advertised and drew large crowds. “Stumbling, Staggering, On They Go! Who will be the next to be carried off the floor?” promoter Rookie Lewis advertised of a 1936 dance marathon in Fife (The Tacoma Times, July 21, 1936). The local press kept a death-watch as contestants dropped out: “The thrilling sprint periods which are in effect at the Hal J. Ross Walkathon in the Century Ballroom each night are proving to be the Waterloo of an average of one contestant each day, with more eliminations expected as this grueling event continues,” trumpeted The Tacoma Times about another contest in Fife (August 1, 1935, p.8).

Many competitors developed signature songs or comic routines. Performed through their perennial exhaustion, these numbers induced the audience to shower the performer with coins. Dancers then gathered up this "floor money," also called "sprays" or "silver showers." Professional comedians who were not contestants also entertained the crowd.

Couples also used sponsorship to generate extra cash. Local businesses paid these couples a small stipend in exchange for wearing the company’s name as they competed. Marathoners also sold autographed picture postcards of themselves to the fans. The price was usually 10 cents. “Dancingly yours,” many read.

Fifteen minutes each hour were allotted for rest. When the air horn signaling a rest period sounded, the contestants exited the dance floor for curtained-off rest areas filled with cots. These rest areas were segregated by sex. Contestants trained themselves to drop instantly into deep sleep as soon as their bodies touched the cots. After 11 minutes the air horn sounded again and the contestants filed back onto the dance floor to begin another hour. Female contestants who didn’t wake at the end of 11 minutes were revived with smelling salts (and slaps), and male contestants were often dunked in a tub of ice water. A Seattle Post-Intelligencer reporter visited the cot area at the 1928 Seattle Armory marathon.

“Here in the half-light they lie, these sprawling, unconscious forms, their cots side by side, their clothing hung in listless disarray ... a girl is sprawled, her lips moving in pain, as she moans incoherently, and jerks her hands. Bending over her is a man, her ‘trainer’ apparently, who massages her swollen feet with some ointment. Beside her, another girl is lying, her mouth open to reveal her gold-crowned molars, while flies crawl across her closed eyes and buzz against her chin” (Alice Elinor, Seattle Post-Intelligencer, August 8, 1928).

Romance Amid Pain

Medical services were available to contestants, usually within full view of the audience. Physicians tended blisters, deloused dancers, disqualified and treated any collapsed dancer, tended sprains, and so on. "Cot Nights," in which the beds from the rest areas were pulled out into public view so the audience could watch the contestants even during their brief private moments, were also popular. The more a marathon special event allowed the audience to penetrate the contestants’ emotional experience, the larger crowd it attracted.

Marathons even featured marathon weddings performed in the arena for a still-shuffling bride and groom. These events (sometimes genuine but usually staged) resulted in gifts for the lucky couple from fans and local businesses.

Spokane audiences enjoyed the “Grand Public Wedding of the Ohio Sweetheart Team. The wedding of Florence Ollie and Jack Stanley, Couple 22, will take place on the Walkathon Floor amidst all the remaining contestants as attendants” (Spokesman Review, August 5, 1935, p.5). The event was broadcast on radio station KGA.

Another popular event was watching a contestant "frozen alive" in a block of ice, a trick done with four hollowed out ice-blocks put together with a person inside. Such an event was advertised as an “added attraction” during the May 1931 Spanaway “Washington State Championship Walkathon Contest … Moro: ‘The Man They Cannot Kill’ Frozen in a cake of ice twice daily” (The Tacoma Times, May 20, 1931).

Twelve Square Meals

Most marathon promoters fed contestants 12 times a day -- oatmeal, eggs, toast, oranges, milk, etc. Couples had to continue the shuffling dance motion while they ate the humble but filling meals. These meals were served at a chest-high table since the contestants ate standing up. Twelve meals a day during the Great Depression was a powerful inducement to many who joined endurance marathons. At a time when many out-of-work Americans were standing in bread lines or simply going without, many marathon contestants reported that, despite the constant motion, 12 meals a day meant that they actually gained weight.

Women constituted up to 75 percent of dance marathon audiences. They watched contestants with the stamina to endure as weeks melted into months. They became invested in the emotional and often sentimental stories the emcee wove about the contestants: the sweetheart couples, the local favorites, the married couples who needed prize money to put food on their children’s plates.

Marathon audiences saw people even harder up than they were themselves. This sight, addictive, drew them back. By 1935, The Billboard magazine claimed that “the average attendance at an evening’s performance of a walkathon is about 2500 people” (Kaplan).

Rigorous and Rigged

In truth, the marathons were usually somewhat rigged, or at least stacked, toward certain couples. Endurance was required, and the demands of the contest grew increasingly brutal as time went on, but the audience failed to understand the degree to which the floor judge and the emcee, both employed by the marathon promoter, worked together to shape events and spin the flim-flam.

Not everyone who visited a dance marathon found it fascinating. Seattleite Blanche Caffiere once attended a Seattle-area show, and remembered that she herself was forced to stand while watching and that the contestants were boring to watch during the day when no formal entertainment was scheduled. Caffiere found it strange to watch people sleeping and eating while they stood (Caffiere interview).

Intense fatigue sometimes led contestants to "go squirrelly," especially during the wee hours of the morning. “Fatigue brought them to a state resembling a coma, a state which seemed to offer relief from the soreness of the day’s travail. During these episodes, contestants hallucinated, became hysterical, had delusions of persecution … acted out daily rituals: they talked to an imaginary companion, grinned vacantly, and snatched objects from the air” (Calabria, p.77). For the audience, watching contestants go squirrelly offered a queasy thrill.

When attendance dropped, promoters began the final push of elimination events. "‘Grinds" were continuous dancing with no rest periods. A grind continued until one or more couple fell and was disqualified, literally ground down in exhaustion. During grinds, even the usual tricks dance partners used to keep each other on their feet (pin pricks, slaps, shaking, pinching, even conversation) were forbidden. “The George C. Cobb walkathon here, at the end of 1460 hours, had two couples and one solo still on the floor,” reported The Billboard of a 1935 contest. “For some time it seems that the kids have had a total lack of respect for derbies, treadmills, figure-eights and dancing sprints, taking them in stride and coming back for more” (November 30, 1935).

"Sadism Was Sexy"

Sprints were just as grueling as grinds but yielded quicker, more dramatic (and therefore more audience-enticing) results. A typical program for a show in which the contestants had danced more than 1,000 hours (about 41 days) was:

"Monday: Zombie Treadmills (1 hour duration)

Tuesday: Figure-Eight Races (25 laps)

Wednesday: Elimination Lap Races (male contestants)

Thursday: Dynamite Sprints

Friday: Heel and Toe Derbies

Saturday: Elimination Races (female contestants)

Sunday: The Argonne Forest" (Calabria, p.35).

Zombie treadmills involved blindfolded contestant teams, often chained or tied together, racing one another. The audience watched this blood sport, drawn by heavy newspaper promotion and live radio coverage.

Seattle native June Havoc (1912?-2010), formerly a child vaudeville star and later an actor in films and on Broadway, spent the early 1930s as a professional dance marathoner. Havoc, who was 14 when she entered her first dance marathon, wrote later of her experiences, “Our degradation was entertainment; sadism was sexy; masochism was talent” (quoted in Calabria, p.64).

Elimination contests served their purpose. Despite high stakes -- having survived hundreds, even thousands of hours -- usually only the top three couples finished in the money. Sometimes audiences were treated to a victory dance in which they could mix with the winners following the close of the marathon. To promoters, a successful marathon was one that generated publicity, made money, and resulted in no arrests.

The August 1935 Bellingham Walkathon at the State Street Auditorium succeeded only in the last respect. The show closed early (a publicity boycott by the Bellingham Herald reduced the crowd) and the victory dance was cancelled. Across Washington, however, dance marathons continued to be mounted, sometimes successfully (a September 1935 Wenatchee show generated such excitement that another "Super Show" featuring immediate brutally intense elimination events opened the day following its conclusion), and sometimes unsuccessfully (as in the May 1931 Spanaway show which ended abruptly when the promoters were arrested).

By the late 1930s, dance marathons had faded from the cultural landscape. Ordinances prohibiting the contests, combined with dwindling "virgin spots," discouraged promoters. America’s entry into World War II sent former marathoners and their audiences to work and to war. Glimmers of the fad remained, however, in roller derbies, which were televised and persisted into the 1960s, and in walkathon/fun runs benefiting charity. Even dance marathons themselves resurfaced, albeit in a form so tame as to be unrecognizable, as charity fundraisers. These modern marathons are usually 12-24 hours, a far cry from the Spokane show that closed October 12, 1935, after 1,638 hours (about two months).