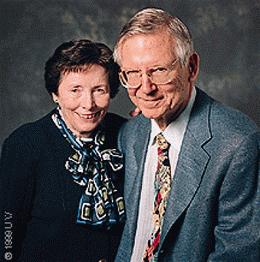

Dr. Ellsworth C. Alvord Jr., former head of neuropathology at the University of Washington’s School of Medicine, and his wife, Nancy Delaney Alvord, have been generous supporters of educational, arts, and public service groups in the Northwest and elsewhere. They've also inculcated the values of philanthropy in their children and grandchildren. Three generations of the Alvord family jointly donated $3 million to create two endowed chairs at the UW’s medical school in 1999. That gift was only part of the family’s long record of service to the community. In 1995, the Washington State Chapter of the National Society of Fund Raising Executives selected the Alvords as the Outstanding Philanthropic Family of the Year. The Seattle King County Association of Realtors named the senior Alvords First Citizens of 1991.

Family Traditions

Ellsworth C. Alvord Jr. -- more commonly known by his childhood nickname, “Buster” -- was born in Washington D.C., in 1923. His father was a successful tax lawyer who established a tradition of family philanthropy when he created the Alvord Foundation in 1937. The family continues to support the foundation, which is based in Washington, D.C. and focuses on educational endeavors.

Buster Alvord was still in high school when he met Nancy Delaney during a summer vacation in Wisconsin. The daughter of a businessman, Nancy was born and raised in Chicago. She went on to Radcliffe (then a women’s college), in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where she studied English literature and history. Alvord, meanwhile, enrolled in Haverford College in Pennsylvania. Their geographic orbits continued to intersect, however. In 1943, six days after Nancy graduated from Radcliffe, they got married in New York City.

Like other wartime couples, the Alvords coped as best they could with rationing and shortages. “I got married in ballet shoes because they were the only things I could find,” Nancy says, with a laugh. “I had on the last silk wedding dress that Saks had in all of New York” (Alvord interview).

Professional Life

Alvord whipped through his undergraduate and medical training during the war years, receiving his bachelor's degree from Haverford in 1943 and his medical degree from Cornell University in 1946. He soon began specializing in diseases of the nervous system. He conducted research at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke in Washington, D.C., from 1953 to 1955. He then joined the faculty at Baylor Medical College in Houston, Texas, as associate professor of neuropathology. In 1960, he was named professor of pathology and chief of neuropathology at the University of Washington’s School of Medicine.

Alvord headed the department of neuropathology at the UW medical school for 40 years, retiring in 2000. Colleagues at the UW credit him with improving the collaboration between immunologists, radiologists, and neurologists in diagnosing neurological diseases. He remains active in his research into the pathology of certain neurological conditions. His primary interests are allergic encephalomyelitis (inflammation of the brain and spinal cord), the causes and prevention of multiple sclerosis, and the growth rate of recurring brain tumors.

He has written, co-written, or edited a copious number of books and articles, including several that have become standard texts in his field. Among his most recent contributions is an article published in 2004, using a mathematical model to predict when treatment of certain kinds of brain tumors (known as “glioblastomas”) would be most effective. Alvord and his co-writers found that because of the diffuse nature of these tumors, the window for effective treatment was smaller than had been thought.

Alvord has been a member of the boards of the Seattle Biomedical Research Institute, the National Multiple Sclerosis Society, and the American Association of Neuropathologists.

Civic Life

Both Alvords have shown deep commitment to their adopted city of Seattle. Neither plays an instrument, paints, sculpts, or performs, but both deeply appreciate art, music, and theater. Nancy is particularly interested in the Seattle Repertory Theatre and the Seattle Art Museum; Buster has focused on ACT Theatre and the Seattle Symphony.

A dedicated supporter of the Seattle Rep, Nancy was the first woman to serve as president of the theater’s board of trustees. She has served on numerous other boards, from the Northwest Women’s Law Center to the Seattle Art Museum. She has also been an active volunteer for the UW. She was a founding director of the UW Foundation and has been a member of the UW Libraries Visiting Committee and the History Visiting Committee, in addition to helping to raise money for the Solomon Katz Professorship in the Humanities.

Nancy Alvord’s diverse range of interests includes the C. G. Jung Society, a nonprofit educational organization formed to provide a forum for the ideas of psychologist C. G. Jung. She became interested in the Jung Society while living in Houston in the late 1950s. In 1973, she established a Jung chapter in Seattle. The Society’s 1,500-volume library at the Good Shepherd Center in the Wallingford neighborhood in Seattle is named in her honor.

Buster Alvord, too, has been a stalwart supporter of the UW. Meany Hall, the Henry Art Gallery, the Department of History, the UW Libraries, the Educational Opportunity Program, and the university’s public radio station KUOW have all benefited from the couple’s largesse.

The UW is not the only educational institution to receive support from the Alvords. They are longtime members of St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church in Seattle, and their interest in church music led them to the Church Divinity School of the Pacific in Berkeley, California, an Episcopal seminary known for its music program. They established an endowed chair in church music and have otherwise aided the school since the mid-1980s. In gratitude for the couple’s “unwavering generosity,” the school awarded them honorary doctorates in 2003. The Alvords have also been involved with the University of Puget Sound in Tacoma, which gave them honorary degrees in 2004.

Family Philanthropy

The family’s most generous gift to the UW was made in conjunction with their four children: sons Chap (who carries the family name as Ellsworth C. Alvord III) and Richard; and daughters Katharyn Alvord Gerlich and Jean Alvord Rhodes. In 1999, the family donated $3 million to create two new endowed chairs at the School of Medicine: the Nancy and Buster Alvord Endowed Chair in Neuropathology and the Cheng-Mei Shaw Endowed Chair in Neuropathology. The later chair honors the work of Cheng-Mei Shaw -- Alvord’s longtime associate in the Department of Pathology. Shaw and Alvord met when Shaw was a resident in neurosurgery at Baylor University. When Alvord moved on to the UW, he brought Shaw with him. The two men and their families have been close friends since then.

The gift was announced as both Alvord and Shaw were preparing to retire from the UW. “Seattle has been so good to us that paying back just seemed natural,” Alvord said. “We have received far more than we have given.” The university was properly grateful. “This University, this community, and this state have been lucky to have two people as thoughtful and generous as the Alvords in our midst for the last 38 years,” said Marilyn Batt Dunn, vice president for development. "We are also fortunate that they have passed on their family values: the Alvord children and grandchildren are following Buster’s and Nancy’s wonderful example of concern for their community” (Columns).

The Alvords and their children have also contributed to the Seattle Public Library Foundation. Separately and together, they’ve donated not just money but time and energy to various other educational, arts, and service organizations, in the Northwest and elsewhere. In 1995, the Washington State Chapter of the National Society of Fund Raising Executives selected the Alvords as the state’s Outstanding Philanthropic Family of the Year.

Nancy Alvord says she doesn’t know how she and her husband passed on their philanthropic values to their children. “I guess we just did it,” she says (Alvord interview). Chap Alvord says it all seemed natural. “We grew up listening to Mom and Dad talk at the dinner table about their volunteer work, and it spilled over into the kids lives,” he says (Columns).

Ellsworth Alvord died following a stroke on January 19, 2010.