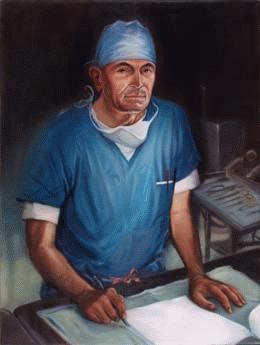

The Hope Heart Institute was founded in 1959 on a figurative shoestring and a literal prayer, in a collaboration between a young Seattle heart surgeon and a Catholic nun. The surgeon was Lester R. Sauvage (1926-2015), a newly minted member of the cardiovascular team at what was then Providence Hospital. The nun was Sister Genevieve (1887-1963), the Seattle hospital’s administrator. Sauvage dreamed of establishing a research laboratory to find better ways to repair damaged hearts and blood vessels. Sister Genevieve made it possible, by providing space, equipment, and encouragement. Together they laid the foundation for what is now one of the leading cardiovascular research and education centers in the Northwest.

Visionary Nun

Sister Genevieve of Nanterre (born Marie Verena Gauthier in St. Jerome, Canada) entered the Montreal-based Sisters of Providence religious order in 1906, at age 19. By that time, the order was operating 20 hospitals and associated schools of nursing in the western United States. Sister Genevieve studied nursing at St. Joseph Hospital in Vancouver, Washington, and later received a Bachelor of Science degree in nursing education from the University of Washington. She spent more than 25 years as director of nursing schools at various Providence hospitals in the West, including those in Everett, Washington; Portland and Medford, Oregon, and Oakland and Burbank, California.

By 1958, when she was appointed administrator of Providence Hospital in Seattle (now part of Swedish Medical Center), she had earned a reputation as an efficient, no-nonsense leader. She was also a visionary. When Sauvage approached her with nascent plans to establish a research laboratory, he found a receptive listener. "She was far-reaching in her vision," he said in a video interview recorded in 2004. "She wanted to have something outstanding at Providence." She quickly agreed to help him set up a research program, "something that was totally foreign to any hospital in Seattle at that time."

Sauvage had settled in Seattle in January 1959. A native of Wapato, Washington (near Yakima), he graduated from the St. Louis University School of Medicine in Missouri in 1948 and returned to his home state to complete his medical training. He was midway through a residency in vascular surgery at King County Hospital (now Harborview Medical Center) when he was drafted into the Army Medical Corps in 1952, at the height of the Korean War. He was assigned to the Division of Experimental Surgery at Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington, D.C. He conducted his first major research project while in the Army, investigating ways to repair blood vessels that had been damaged by rifle fire or shrapnel. The experience fostered what became a lifelong interest in vascular research.

After being discharged from the Army, Sauvage completed his residency at King County Hospital and a second one at Children’s Medical Center in Boston, Massachusetts. He then joined the surgical staff at Providence Hospital. A few months later, Sister Genevieve offered to help him establish a laboratory to continue the kind of research he had begun at Walter Reed.

The first home of the Reconstructive Cardiovascular Research Laboratory -- precursor to the Hope Heart Institute -- was an old white frame house, owned by the Sisters of Providence and made available to Sauvage through the intercession of Sister Genevieve. Long since demolished and replaced by a parking lot, it was located at 528 18th Avenue, across the street from the hospital. Sister Genevieve left the hospital in 1961, when she was named Provincial Councilor for the Sisters of Providence in the West. By then, the groundbreaking studies that would bring international attention to the fledgling laboratory were well underway.

Pioneering Research

Sauvage worked essentially by himself until 1961, when he was joined by research pathologist Knute E. Berger (1915-1990), who remained a close associate for more than 20 years. That year, the laboratory received its first substantial outside financial support, a $355,000 grant from the New York-based John A. Hartford Foundation, established by heirs of the founder of the A & P grocery store chain. The foundation would continue to help finance research done by Sauvage and his associates for the rest of the decade.

The laboratory’s early work was focused on the design and testing of blood-vessel grafts and the repair of leaky heart valves with tissue from the pericardium (the sac around the heart). Sauvage conducted hundreds of experiments, primarily on calves and dogs, in an effort to develop new ways of bypassing obstructions in arteries. Fats, cholesterol, and other substances can build up in the arteries over time, forming deposits ("plaque") on the walls. These deposits narrow the arterial passageway and interfere with the flow of blood to the heart, causing pain ("angina") and ultimately damaging the heart muscle. Sauvage theorized that segments of veins could be grafted onto the arteries, creating detours around the blockages and thus restoring blood flow.

In 1962, Sauvage became the first researcher to successfully use vein tissue as a substitute for a coronary artery, in a series of experiments on dogs. Another surgeon, David C. Sabiston Jr. of Duke University in North Carolina, made a similar attempt on a human patient that year, but the patient died of a stroke. Dubious about the value of the procedure, Sabiston did not publish his results until 1974. Sauvage’s results, published in the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery in December 1963, marked an important milestone in the development of coronary artery bypass surgery, today the most common operation on the heart.

The experiments were conducted under challenging conditions. Heart-lung machines, only recently developed in rudimentary form for human patients, were not available for animal research. That meant the dogs’ hearts could not be stopped during the operations, forcing Sauvage and his assistants to work extremely quickly. Despite the limits, 20 percent of the experimental grafts remained open and functional after the surgery. Sauvage said later he was "amazed" that any of them worked. Still, most of the dogs died as a result of blood clots that developed in the grafts.

Sauvage attributed the failure rate to the fact that he was using the external jugular vein as a bypass conduit. In human patients, he added, the saphenous vein (in the leg) would be a better choice, because its walls are thicker and the diameter a closer match to the coronary artery. In general, he concluded, coronary bypass grafting was "sound in principle" (Sauvage, 833).

One year after Sauvage published the results of his animal studies, a Houston surgeon performed the first successful coronary bypass operation on a human patient, using a segment of the saphenous vein. However, his work gained little notice at the time. It was Dr. Rene Favaloro of the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio who refined and popularized Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting (CABG), beginning in 1967. His first grafts were also created from the saphenous vein -- a method Sauvage had suggested four years earlier.

Sauvage became best known for designing synthetic blood vessels and arteries made from Dacron. He and his team discovered that the porosity and texture of the polyester fabric allows endothelial cells (those lining the heart and blood vessels) to grow around the graft, just as they do around living tissue. The Dacron-based "Sauvage graft," patented in 1971, earned royalties for many years. Sauvage ploughed all the money back into the lab, to help support further research.

New Directions

By the mid-1970s, Sauvage and his associates at what had been renamed the Reconstructive Cardiovascular Research Center had published more than 40 scientific papers on the design and healing of artificial arteries and heart valves. Among their contributions was a standardized method for using a patient’s own blood to "pre-clot" blood-vessel grafts made from synthetic materials. The process prevented internal bleeding and promoted healing after the grafts were implanted.

Sauvage had become a recognized authority on venous grafts, and was frequently invited to lecture on the topic at medical meetings around the world. At one such conference, in Australia in 1979, he met Dr. Vijay Kakkar, director of thrombosis (blood clot) research at King’s College Medical School in London. Out of that relationship came an ambitious effort to greatly expand the center’s scope and influence.

The center was still a relatively modest undertaking at the time, with a staff of about 10 researchers. Sauvage embraced a grander vision. He dreamed of bringing together an international team of hematologists, biochemists, immunologists, and other specialists who could not only develop better ways of treating coronary disease but also ways to prevent it altogether.

Ambitious Plans

In 1980, Sauvage launched a campaign to raise $30 million to transform what had once been a one-person operation into one of the world’s leading heart research institutes. He organized a local board of directors, consisting of wealthy and influential community figures; assembled an international board of governors, studded with the names of famous people; and hired a public relations firm to coordinate fundraising. Bob Hope (1903-2003), arguably the best-known entertainer in the world at that time, agreed to lend his name to the cause. Accordingly, Sauvage announced that the center would be renamed the Bob Hope International Heart Research Institute. Kakkar, the prominent London physician, would serve as its director.

The plans called for the construction of a $5 million world-class research center, outfitted with $3 million worth of the latest laboratory equipment, supported by a $22 million endowment. Sauvage wanted the institute to operate with private funds rather than government grants. Although the center had received some federal funding in the past -- including a $170,000 grant from the National Heart and Lung Institute in 1976 -- he objected to the "bureaucracy" involved in publicly supported research. Ironically, the institute would become increasingly reliant on government grants as it expanded its commitment to basic scientific research in the 1990s.

The campaign fell far short of its goal. By the end of October 1983, only $6 million of the hoped-for $30 million had been raised. Construction of the new building was postponed several times and finally abandoned. Instead, the institute’s existing quarters were remodeled and expanded. Kakkar came to Seattle briefly, but returned to London when it became clear that the grand plan would not be realized.

The association with Bob Hope ended quietly by mutual agreement in late 1987. The entertainer had had little involvement with the institute, and in fact, the use of his name proved to be a mixed blessing. Some prospective donors assumed that the institute was based in Palm Springs, where Hope lived, and that the Seattle operation was only a branch office. Others believed that the wealthy entertainer was supporting the institute and thus it was not in need of further help. In early 1988 it was announced that the organization would be renamed the Hope Heart Institute, dropping the reference to the entertainer but retaining the name "Hope" for its symbolic value. As a spokeswoman explained at the time, "in research, hope is the greatest gift one can give" (The Seattle Times, 1988).

Expanded Research

Despite the failure of the campaign for a new building, the scope of research at the Hope Heart Institute continued to broaden. By the early 1990s, a new generation of scientists had shifted the institute’s focus from clinical applications to basic science. Clinical research, of the sort pursued by Sauvage and his early associates, has direct application to human patients. Basic science is more amorphous. As explained by Phillip Nudelman, the institute’s president and chief executive officer since 2000, "Basic science is exploring and investigating. It’s the very earliest level of scientific investigation: for example, studying enzymes, how cells grow, what stimulates them to grow. It’s usually the first step toward contributing knowledge to another step, and another, and another, until the research can be translated to the clinical area" (Nudelman interview).

Basic science is also, he adds, extremely expensive. Hope scientists were making important contributions to the understanding of the cardiovascular system at the cellular level, but the institute was going further and further into debt to help finance their work.

The emphasis on basic science accelerated after Sauvage retired as president and medical director of the institute in 1997. He was replaced by William P. Hammond, director of medical education at Providence Seattle Medical Center and associate professor of medicine at the University of Washington. Hammond recruited a number of preeminent scientists, each supported by government grants and accompanied by individual research teams. Among the newcomers were vascular biologists E. Helene Sage, who studies angiogenesis (the growth of new blood vessels); Thomas Wight, whose work focuses on the interactions of the cell and its matrix at the molecular level; and surgeon Margaret Allen, the first woman to perform a heart transplant operation in the United States. Allen, who founded the University of Washington Medical Center’s Regional Cardiac Transplant Program in 1985 and served as its director until 1996, joined the Hope in 2001 to pursue a number of research interests, including gene therapy and other methods to repair the heart, rather than replace it.

Several of the new projects involved the emerging field of tissue engineering -- a technique in which a patient’s own cells can be used to create blood vessels and perhaps other organs. For example, Wight’s lab collaborated in a five-year, $2.5 million project, funded by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, to "grow" blood vessels from snippets of skin and vein. The samples are placed in a lab dish and bathed with growth enhancers to stimulate the production of collagen and elastin. As the tissues expand, they are harvested, stacked, and rolled into "home grown" vessels six to eight inches long. In November 2005, Cytograft Tissue Engineering, a San Francisco-based biotechnology company, announced that engineered vessels had been successfully implanted in two kidney-dialysis patients from Argentina. Hope Heart proudly issued a news release pointing out that Wight had been part of the team working with Cytograft.

Allen’s lab, meanwhile, was investigating ways to use a patient’s own heart-muscle cells to grow patches of new heart tissue. This could be a way of replacing cardiac-muscle cells destroyed during a heart attack with new ones. In 2003, this project was awarded $500,000 from the National Institute of Biomedical Engineering.

By 2004, Hope Heart researchers were being supported by $3.5 million in federal grants. The problem, Nudelman says, is that the government wasn’t paying all the bills. "It’s a difficult financial issue because most basic science is financed by the federal government," he says. "But the government doesn’t finance all the costs of doing the research. It pays for the direct costs of a study but only a portion of the indirect costs -- overhead, administration, etceteras." Large institutions can spread the difference among many scientists, reducing the subsidy. The Hope, however, "didn’t have enough scientists and grants to be economical. We were going into the hole to fund basic science" (Nudelman interview).

Retrenchment and Redirection

Nudelman was coaxed out of a brief retirement as president and chief executive officer at Seattle-based Group Health Cooperative in order to take on the same role at the Hope. Among the challenges was a $2 million deficit. His initial task was to help the institute survive financially. "It was clear we were not going to be able to do that by doing basic science funded by the government," he says. "That’s when I started looking for a partner" (Nudelman interview).

In January 2004, the Hope announced that its 34 research scientists would move into quarters at the Benaroya Research Institute (BRI), a nonprofit biological research facility at Virginia Mason Medical Center. The alliance added cardiovascular research to longstanding work in diabetes and immunology at BRI. It allowed the Hope to move its researchers into high-quality labs, save money on overhead, and use the savings to expand its programs on education and prevention of heart disease.

The Hope Heart Program at Benaroya Research Institute continues to seek new ways to combat heart disease through the study of cells, blood vessels, and gene therapies. It includes a department of "translational medicine," directed by Margaret Allen, which attempts to take the discoveries of basic science and "translate" them to clinical practice. "As a heart transplant surgeon, my earlier research was devoted to preventing rejection of transplanted hearts," she says. "Now my goal is to eliminate the need for heart transplants in the first place by preventing heart failure" (Hope Heart Forum).

With basic research programs moved to BRI, the Hope added a new component through a partnership with a group of cardiologists who were involved with clinical trials, testing new drugs, devices, and treatment methods on patients who volunteer for the studies. The Hope’s clinical research program is headed by Thomas A. Amidon, a Bellevue cardiologist. About two dozen cardiologists, most based on the east side of Lake Washington, participate. At any give time, more than a dozen trials are underway. Recent examples include a study to compare the benefits of two lipid-lowering drugs in patients experiencing a heart attack or chest pain; another to determine the best time to administer an anti-blood clot medication to heart patients; and another to see if a new anti-inflammatory drug can improve patients’ chances of surviving a serious heart attack.

What Nudelman calls "a very skinny staff" of about 35 remains at the Hope’s headquarters at 1710 E. Jefferson Street, around the corner from the site of the original laboratory. The staff operates education programs, administers the clinical research program, and raises money for further cardiovascular research. Nudelman points out that "Every dollar that is donated from the public to the Hope goes directly to research or education -- 100 percent." Administrative costs are financed with revenue from Hope Publications, which produces health-oriented newsletters and brochures.

Lester Sauvage, now medical director emeritus, continues to influence the institute that he founded nearly half a century ago. It was at his behest that the Hope became involved in a five-year epidemiological study launched in 2003 in cooperation with Health Net, a major medical insurance provider on the East Coast. About 6,000 Health Net enrollees are participating in the study. Half will receive a copy of Sauvage’s The Better Life Diet and bimonthly copies of the Hope Health Letter, containing information on diet, exercise, stress reduction, and other health topics. The control group will not receive the material. The total cost of medical claims filed by the two groups will be compared every six months. The goal is to see if regular exposure to health information will make a difference in medical costs.

Sauvage thinks this is the most important study he’s ever been involved with. "Prevention is where we should be," he says, "more than having more sharp knives and more operating rooms and more talented surgeons. We’re not going to defeat heart disease with a knife" (video interview).