Upon the Hoquiam River, in Grays Harbor County, where the fresh water empties into the sea, is the little town of Hoquiam, Washington. From its earliest history through the rough-and-tumble era of lumber barons and labor radicals, Hoquiam’s history has been inextricably tied to the vast, dense woods that surround the town. And although the woods produced a great bounty for a few well-placed individuals, boom and bust cycles and exploitation bred unemployment, poverty, and scores of industrial accidents among the great majority of the region’s peoples. Through the depressions and federal logging restrictions Hoquiam has persisted as a small lumber town, one that today lives up to its motto: “Rebuilding Our Proud Past with A Promising Tomorrow.”

First Peoples

In the region now called Grays Harbor County, indigenous peoples lived for hundreds of years in advance of white settlement. There, the Quinault, Humptulips, Wynoochee, and Chehalis Indian tribes all thrived in the lush forests, along the river banks, and on the beaches, where hunting, fishing, and gathering provided easy and abundant food sources. According to Grays Harbor historian Ed Van Syckle, the Humptulips tribe may have controlled the Hoquiam river valley, "but there are indications that the Hoquiam Indians considered themselves a distinct group" (Van Syckle, River Pioneers, 56).

Because of the bounty provided from the natural environment, most tribes had ample leisure time to craft rich cultural traditions, including the potlatch, an elaborate ceremony hosted by a tribal elite to demonstrate his prosperity by spreading it among his invited guests. Many members of these tribes were skilled woodworkers: Their ability to cut and shape the region's most extensive resource, including cedar houses and canoes, was as finely tuned as anywhere else on Earth. Local indigenous groups were responsible for many of the place names in and around Hoquiam. “Hoquiam” itself was the name of a local tribe, and the towns of Humptulips, Quinault, and Satsop were all derived from tribal names.

As with indigenous peoples the world over, the spread of European pathogens was the most responsible for the rapid decline in coastal Indian populations during the nineteenth century. Evidence stemming from a myth as retold by Lucy Heck, a Humptulips Indian, suggests the possibility of successive small-pox epidemics inflicting great damage on coastal Washington tribes shortly before 1830. No specific figures on the loss of Grays Harbor tribes are available for an 1853 epidemic, but testimony provided by Bob Pope, a Quinault Indian informant, indicated that much of his tribe was wiped out by an epidemic that swept through the region near that date.

Wars, too, took their toll on Indian groups. In his book The River Pioneers, Ed Van Syckle captured a number of early settlers’ and Indians’ stories of inter-tribal raids and battles, including several involving the Chehalis Tribe. During the 1850s, as news of Indian raids and killings in other parts of the territory filtered to the early white settlers on Grays Harbor, they worried over the possibility of conflict with local tribes. A number of these settlers, including Martha Medcalf, one of the white women to settle in Grays Harbor, filled their journals with entries attesting to their fear of Natives and their dutiful, armed watches for Indian raiders.

What disease could not accomplish was done by treaties signed and enforced by federal agents. In January 1856, after months of intimidation and prodding by Washington governor and Indian agent Isaac Stevens (1818-1862), several coastal tribes signed treaties that led to or confirmed a number of reservations, including the Quinault reservation, which is located in northwest Grays Harbor County and stretches slightly into southwest Jefferson County. A number of tribes, including the Chehalis, refused the agreement and became what were known as "non-treaty Indians," a designation that deprived them of even the meager provisions of federal beef, blankets, and land provided to "treaty Indians" (Van Syckle, River Pioneers, 64).

Despite American imperial conquest over their lands, the ravages of disease, and being pushed onto reserves, many Indians were able to survive and even resist white domination. The Humptulips peoples flatly refused to sign treaties with whites and refused to leave their ancestral homelands. During treaty negotiations with Governor Stevens held in Cosmopolis during February 1855, tribal leaders proved themselves to be tough bargainers, refusing to kowtow to the federal agent. Others smuggled alcohol into camp as a direct affront to Stevens. who had banned its consumption during negotiations.

White Settlement

The first white man to settle in what is now Hoquiam was James Karr, who moved into Grays Harbor from Oregon in 1859. He was joined shortly thereafter by Ed Campbell (1835-1919), who in 1867, applied for and received a post office at the mouth of the Hoquiam River. While applying for the post office Campbell was forced to choose a name for the settlement that was already almost a decade old. After some wrangling over the spelling, Campbell chose the name “Hoquiam,” the word local Indians used for the river, although previously the word had most commonly been spelled “Hokium.”

Campbell became the first postmaster in the new settlement, a position he held until his retirement in 1887. He also built a house in March 1872, which now stands at 18th Street and Riverside Avenue as the oldest home in Hoquiam. To accommodate the few children who were born in Hoquiam or who traveled there with their parents, a small school was established inside the home of Johnny James (1841-1929) in 1873.

Hoquiam and Lumber

From 1880 onward, Hoquiam's growth depended primarily on the lumber industry. The first of Hoquiam's early mills was a joint project by A. M. Simpson, a San Francisco lumber baron, and George H. Emerson (1846-1914), his agent and the man who became widely known as "the Father of Hoquiam."

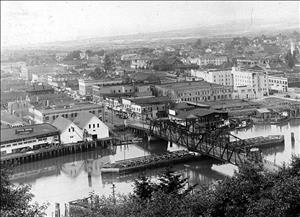

In 1881 Emerson purchased 300 acres to build the mill from early settler Johnny James. Laborers completed the mill, which became known as the North Western Lumber Company, in August 1882. Emerson became its first president, and in a sign of lumbermen's domination of local affairs that was to follow for the next century, he determined how and where the town's streets should be arranged. Alongside the great mill grew a host of service industries. By 1890, Hoquiam was already home to several grocery stores, saloons, restaurants, and hotels. Making these businesses work were teams of clerks, teamsters, porters, and longshoremen.

The great impetus behind the incorporation of Hoquiam as a city came from these small businessmen and major capitalists, men like Emerson, who, along with serving as the general manager of Hoquiam's first mill, was also president of the Hoquiam Board of Trade and member of the first town council. Joining him on that first council were lumbermen W. D. Mack and John F. Soule.

Working to Get a Railroad

A key to the move for incorporation was the need to wield an effective lobby group for Hoquiam-friendly policies, namely legislation favorable to the lumber industry, the attraction of immigrants to work in the mills and woods, and most importantly, the extension of a railroad into the city. Emerson and his colleagues understood the central importance of the railroad to their project to develop Hoquiam and exploit the region's vast resources.

In the 1880s and 1890s cities in Washington state fought bitterly over the extension of rail lines into their settlements and cities. Although the Northern Pacific did not extend its line into Hoquiam until 1899, rumors that Hoquiam might become the railroad's Western terminus attracted immense settlement and investment. The year 1889 proved a boom year for Hoquiam speculators. In that year alone, during which Hoquiam organized as a city and rumors of the railroad’s imminent arrival were loudest, Hoquiam's population more than tripled from 400 to 1,500. In 1890, building in the city tripled, and property values advanced by more than 1,000 percent.

Despite the town's efforts and despite the massive influx of people and outside investment, Hoquiam’s dreams of luring a railroad were not realized until a full decade after the city’s first government was established. Owing in part to this absence of a railroad line into Hoquiam, the North Western mill maintained a near monopoly over the city’s lumber trade until the first years of the twentieth century. By 1897, only one additional mill -- the E. K. Wood company -- had been built in Hoquiam. During the 1880s and 1890s, a number of logging operations were founded to supply the North Western with logs. However, most of the truly massive Hoquiam logging ventures did not get their start until the early twentieth century.

Finally, in 1899, four years after the Northern Pacific Railroad reached Hoquiam’s sister city of Aberdeen, the line was extended into Hoquiam, thus completing the capitalist project begun a decade earlier. Although its earlier access to rail transportation gave Aberdeen an early lead in population, capital, and prestige it would never relinquish, the railway brought massive new investment into Hoquiam, particularly by lumbermen. Lumber and shingle shipments from the town, previously confined to water-based transport, increased dramatically.

Lumber in the Twentieth Century

During the first years of the twentieth century, a whole bevy of massive mill operations entered Hoquiam. Brothers Robert Lytle (1854-1916) and Joseph Lytle had the Hoquiam Lumber and Shingle Company built in 1902. By 1906 it was among the world's leading cedar shingle manufacturers. The Grays Harbor Lumber Company followed a year later; its manager N. J. Blagen's lumber interests supplied all of the lumber for the Northern Pacific rail line from Ellensburg over the Cascades to a point four miles east of Green River Hot Springs (in east King County).

Hoquiam was home to a large and well-established sawdust baronage, but no other family compared to the Polsons, whose holdings included two sawmills, a shingle mill, two mansions, 12 logging and construction camps, 100 miles of logging railroad, a huge quantity of logging equipment, and produced 300 million feet of logs annually. Alex Polson settled permanently in Hoquiam during 1882, his pursuits taking him from real estate, to county accessing, to logging. In 1891 Alex and his brother Robert combined their logging interests into the Polson Brothers Logging Company, which, 12 years later, after affiliating with the Merrill and Ring Corporation, was renamed the Polson Logging Company.

Along with the Polsons, some 300 logging firms have operated on the harbor since the 1880s. Varying in size from the massive Polson camps to the many small family-run operations, loggers and logging become synonymous with Grays Harbor, loggers' paychecks supporting local businesses and their rich cultural traditions giving the region a distinctiveness that has been marveled at by scholars and journalists for more than a century.

Because of the nature of the work, most loggers remained out of town throughout most of the year, although during shut-downs, the streets of Aberdeen and Hoquiam swelled over with woodsmen. Because of the influx of mill and logging jobs, particularly after 1900, Hoquiam's population grew more than five-fold, from 1,500 in 1890 to 10,000 in 1920. One of the clearest signs of the city’s development was the growth of enrollment in Hoquiam public schools. In 1905 Hoquiam registered 727 students, 100 more than the previous year.

The Lumber Elite

Despite the widely held conception of lumbermen as freewheeling individuals, mill owners and boss loggers required little prodding to form their own associations to control prices, fight unions, and socialize with their own. Lumber and shingle mill owners like Robert Lytle and George Emerson rose to leadership positions in the regional and national lumber-trade associations. When the Hoquiam branch of the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks formed in 1907, its membership consisted primarily of Hoquiam's elites, including Frank Lamb, George Emerson, and Robert Lytle.

In 1912, during a strike of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) at several Grays Harbor and Pacific County mills, Hoquiam residents formed their own citizens' committee, a hastily organized vigilante group composed of local businessmen, to physically remove the strikers from the embattled towns.

During the 1910s and 1920s, harbor lumbermen participated in a host of state-wide organizations designed to curb radical influences by hiring "detectives" who were essentially labor spies and by developing blacklists of militant workers. The U.S. Department of Justice and Department of War hired labor spies to keep watch over radical and union activities in Hoquiam, Aberdeen, and the surrounding woods during the late-1910s and 1920s. Washington State Governor Ernest Lister's Secret Service, organized during World War I, also sent agents to cities in Grays Harbor to infiltrate unions, spy on radicals, and report on their findings to employers and local authorities.

Hoquiam: One-Half of the "Twin Cities"

Hoquiam, along with its sister-city, Aberdeen, have been frequently referred to as the "Twin Cities" of Washington. Historian Richard M. Brown has even written that “except for their separate municipal governments, the twin cities were virtually one unit” (Brown, “Lumber and Labor”).

The proximity of Hoquiam to Aberdeen, and their numerous commercial ties, led to a few widely publicized efforts to merge the two towns. One such effort played itself out in the 1906 election as members of the Aberdeen and Hoquiam business communities pushed a vote to remove the county courthouse from county seat Montesano to a spot straddling the "twin cities." The county seat removal proposal was derailed by the joint efforts of union militants J. G. Brown of the Hoquiam shingle weavers union and William Gohl of the Aberdeen Sailors’ Union of the Pacific, who accused its boosters of running a graft at the taxpayers’ expense.

Workers themselves then led efforts to tie the communities closer together. The Grays Harbor Trades and Labor Council and the Hoquiam Labor Council developed plans to construct a massive labor hall on ground between the two cities, one that, according to the Grays Harbor Post, “organized labor will have the credit for driving the golden spike uniting the two cities” (“To Build,” Grays Harbor Post).

Workers Unite

The most tragic legacy of the lumber industry was the toll exacted on human life by capitalist relations in the logging industry. While employers like Alex Polson and Robert Lytle grew rich off the profits generated by their workers' labor, loggers and mill workers fell victim to a frightening array of injuries. During the 1910s and 1920s, notices of lumber workers’ deaths appeared almost daily in the Daily Washingtonian, the city’s primary news organ. On June 1, 1910, John A. Wise, a Hoquiam sawyer, died after his head was split open by a cut-off saw. A year earlier lath trimmer Albert Kennedy's leg was sawed off three inches above the ankle, for which he received no compensation.

The shingle weavers became the first lumber workers to organize themselves into a union. The union was formed, in part, to ensure its members were properly compensated for the number of fingers and hands lost on the job. During a single month in 1907, six Hoquiam weavers received serious cuts from the saws, while local president J. H. Cramer was forced to retire from the mills because of his respiratory ailment. Between 1902 and 1915 shingle weavers constituted the militant left-wing of the Hoquiam labor movement, which forced the Hoquiam Labor Council to consider and adopt planks considered too radical in many other towns.

Along with the shingle weavers, a number of conservative, socialist, and syndicalist labor unions formed in Hoquiam and her surrounding towns. The purposes of the unions varied dramatically. Some served primarily as fraternal bodies, whereas others urged municipal reform, and a surprising number supported the election of left-wing political candidates and socialist revolution.

Others, too, were thinly veiled excuses for white supremacy, a means to guarantee that the Nordic races maintained control of certain relatively high-paying trades. J. G. Brown, socialist president of the Hoquiam shingle weavers, organized a protest meeting in March 1904 against employers’ hiring of Japanese laborers. The meeting drew a massive crowd and was addressed by local and state-level union representatives, businessmen, and city officials.

In 1906 Hoquiam had eight labor unions, and during the annual Labor Day Parade, the combined Hoquiam-Aberdeen labor movement regularly turned out well over a thousand marchers. Organized labor retained a strong presence among the Hoquiam carpenters, teamsters, tailors, and bartenders, and Hoquiam women workers organized in label leagues and in the laundry workers’ and printers’ unions.

Clubs and Societies

While unions served to channel the collective protest of workers into reformist and revolutionary activities, numerous capitalist-class and middle-class clubs formed in Hoquiam to trim off some of the rough edges of capitalism. Central to these progressive tendencies were women's clubs, the largest of which was the Women's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), a group initially formed to curb the excesses of alcoholism but that soon turned to other social issues.

Hoquiam and Aberdeen women also founded a number of cultural clubs where they could collectively enjoy music, literature, and one another's company. In 1891 articles of incorporation were filed for the Aberdeen Library Association, and during the early twentieth century it was joined by the Associated Charities of Hoquiam, the Hoquiam Cemetery Association, the Emergency Garden League, and the Hoquiam Business Women's Club. In 1911, Hoquiam was home to 11 churches and one branch each of the Salvation Army and Young Men’s Christian Association. So great was the spirit of joining in Hoquiam that by 1910, the city housed 22 secret societies.

Race and Ethnicity

Racist clubs too found their way into Grays Harbor. In 1908 a local of the Asiatic Exclusion League was founded in Aberdeen, and the Fraternal Order of Eagles, with locals in Aberdeen and Hoquiam, explicitly welcomed whites-only, denying membership to anyone not of the “Caucasian race.” Although organizations based primarily on racism never enjoyed the growth and success of the class-based vigilante movements organized to drive working-class activists from town, the sheer number of whites-only clubs, unions, and businesses institutionalized white supremacy on the harbor.

Hoquiam and its sister-city Aberdeen were composed of ethnically diverse populations whose members formed clubs, built halls, and maintained a degree of ethnic solidarity against the pressures of Americanization. Norwegians, Swedes, and Croatians came to the harbor in large numbers between 1890 and 1920, but the largest immigrant group to settle in Aberdeen and Hoquiam were the Finns. By 1910, Hoquiam was already home to a Finnish hall, several saunas, a Finnish Templars Society, while festive athletic competitions and theatrical performances usually accompanied meetings at the Hoquiam Finn Hall. On May 1, 1909, the Hoquiam Finnish Workingman’s Association was incorporated with the State of Washington, its declared purpose being: “to educate, elevate and improve mankind, and particularly the workingman, mentally, morally, and socially” (“Articles of Incorporation,” May 1, 1909).

So important was the purchasing power of these Finnish workers to local businesses that several-dozen Grays Harbor small businesses advertised in the Toveri, the Finnish-language socialist newspaper printed in Astoria, Oregon. During the late-1920s and 1930s members from both groups joined the Communist Party, which gave communists a major stronghold in the region. Today, Finn Electric continues to operate in Grays Harbor, and several Koskis, Makis, and Katainens maintain the strong Finnish American presence in the region.

A Town and Its Newspapers

Hoquiam residents received their news from a dizzying array of newspapers during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. There were at least 20 Grays Harbor County publications founded before 1900. During the first three decades of the twentieth century, a steady flow of Republican, Democratic, Socialist, union, ethnic, and other area newspapers were issued. Most lasted only a very short time; others were started on the harbor and then moved on to Everett or Seattle. There were at the minimum 60 publications in Aberdeen, Hoquiam, Cosmopolis, and other Grays Harbor towns; the number was more likely one or two hundred.

Alongside the labor, socialist, and ethnic newspapers that circulated among the harbor towns, Hoquiam's mainstream newspapers included Gant's Sawyer, the Gray's Harbor Gazette, and the Hoquiam American. In addition, the Grays Harbor Washingtonian, formed in 1889 by Otis Moore and incorporated with a stock of $15,000 in 1907, became one of the region’s most widely read and respected newspapers.

Its well-known editors included Congressman Albert Johnson (1869-1957), a Taft Republican who supported woman suffrage and opposed labor unions and immigrants, whom he described as the "ignorant hordes from Eastern and Southern Europe, whose lawlessness flourishes and civilization is ebbing into barbarism" (Willis, "Henry McCleary"). Johnson served as Congressman between 1913 and 1933; his congressional career climaxed in 1924 with the passage of the Johnson-Reed Act, which applied a stringent quota system to American immigration policies. He was swept out of office with the coming of the New Deal and Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Before leaving Hoquiam, Johnson launched a second paper, one designed solely to channel his hatred and fear of immigrants and labor activists into a potent and destructive outlet. The Home Defender was published in Hoquiam between May 1912 and March 1913, at which time it, along with Johnson, departed for Washington, D.C.

A second editor, Russell Mack (1891-1960), also used his position with the Washingtonian to launch his congressional career. Mack served in the United States House of Representatives between 1947 and 1960. Like Johnson before him, Mack used his prestige to launch attacks on radical labor-unionists Shortly before the murder of Laura Law (1914-1940), wife of International Woodworkers of America official Dick Law (1908-1953), Mack declared at a public meeting that “The Dick Laws must go!” (Hughes and Beckwith, On the Harbor, 112-113). Murray Morgan, a widely read Pacific Northwest historian, worked on the “Washie” between 1937 and 1941. Morgan covered Law's murder, and subsequently produced the novel The Viewless Winds based on those events.

Writing on the competition between the Washingtonian and the cross-town Aberdeen World, Morgan wrote, “The World was older, bigger, richer, better staffed. The World, in fact, was a lot better paper, though even now I feel a twinge at saying so. David might concede that a reasonable man would bet on Goliath, but admit the bigger fellow to be better? Hardly” (Hughes and Beckwith, On the Harbor, 86).

The Washingtonian lasted as a daily paper between 1903 until 1951, when it changed into a weekly. The last edition of the “Washie” was printed in 1957.

Speeding Up the Cutting Down: the 1920s

Lumber was the lifeblood of Hoquiam, Aberdeen, and all of Grays Harbor. Throughout the first quarter of the twentieth century, Grays Harbor County retained its title as the greatest lumber-producing and lumber-shipping region in the world.

During the 1920s, new machinery, speed-ups, "production-pushing" foremen, and the increasing reliance on gyppo loggers (small, independent operators) pushed the harbor region into over-production. Grays Harbor ports had long been the greatest lumber shippers in the world, but previous accomplishments paled in comparison to those reached in the twenties. In 1922, her mills cut more than one billion board feet of lumber. The list of mills was headed by the Grays Harbor Lumber Company of Hoquiam, which cut 120 million board feet. Two years later, Grays Harbor ports became the first in the world to ship a billion board feet by water, a feat no other port came close to matching.

In his aptly titled They Tried to Cut it All, Grays Harbor historian Ed Van Syckle captured the furious pace of the industry: "Only Heaven alone can describe those years -- timber! -- the challenge of it, the appalling labor, the deeds and misdeeds in its name" (Van Syckle, They Tried, 256). During the first 64 years of sawmilling in the region approximately 31 billion board feet of lumber were cut on the harbor. By the time production levels began to drop in 1930, continued Van Syckle, "loggers were working 30 to 50 miles back in the hills." (Van Syckle, They Tried, 258)

The speed-ups, long hours, and pressure to produce these records exacted a terrifying toll upon the workers who made them possible. Through lackluster industrial safety regulations and minimal compliance with regulations that were in place, on-the-job, dreadful injuries among the workers mounted throughout the 1920s. Between 1920 and 1929, 452 sawmill workers were reported killed on the job in Washington state, a more than a four-fold increase from the previous decade. During a 1927 shingle strike, one weaver proclaimed: "When the workers were informed that their wages were cut from 50 cents to $1.00 a day, they held a meeting and agreed that they could not afford to risk their health and the mangling of their hands for so small a wage" (“Mill Workers,” Daily Washingtonian, March 3, 1927).

Overproduction, competition from other building materials, and decline in the demand for lumber all pushed the industry towards depression well in advance of most of the nation. To combat falling prices and low lumber consumption, employers lowered the wages of their employees and laid off workers. Strikes were waged on the harbor every year between 1923 and 1927, most often to rollback wage cuts. In 1923, IWW William McKay was shot in the back of the head by a company gunman at the Bay City Mill in Aberdeen. In 1925 and 1927 un-unionized workers successfully struck to roll back wage cuts after management imposed them. In contrast, the Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen (4Ls), a company union organized by the military during World War I, voluntarily lowered its members’ wages across the Pacific Northwest, including at the Polson camps near Hoquiam.

The lagging lumber economy pushed a number of capitalists into searches for new industries and new profits. During the 1920s a number of plywood, pulp, and paper firms moved onto the harbor. In early 1927, the pages of the Daily Washingtonian were filled with reports of pulp plants moving to Aberdeen and Hoquiam, and in 1928 the Grays Harbor Pulp & Paper Company began to churn out pulp.

At the Posey Manufacturing plant, a firm founded in 1908 that specialized in piano sounding-boards made of spruce, mill managers employed a sophisticated welfare capitalist scheme, offering pension plans and seniority to their employees in return for labor peace. The pages of their house organ Poseygram mixed boosterish appeals to company ball teams, bands, and picnics, with a section of "I-D-I-O-T-O-R-I-A-L-S" aimed to mock lazy workers and socialists.

The Great Depression

The recession in the lumber industry was greatly exacerbated by the Great Depression, as unemployment and poverty spread across the nation at new and frightening rates. By 1932 only about one-fifth of the lumber industry was operating, and approximately 50 percent of those still employed were working only parttime. According to one University of Washington study of unemployment, Grays Harbor County was in especially dire straights:

"Probably no county in the state is in worse financial shape than Grays Harbor County ... . It is difficult to see how the county can carry on. Many county functions will have to be discontinued, and all welfare activities will have to be reduced very drastically" (Harris, “County Finances in Washington,” 370).

To this, many unemployed workers responded with creative action, fending off starvation with direct action and political action aimed at holding their political and economic leaders. Unemployed Councils affiliated with the Communist Party formed in Hoquiam and Aberdeen during the early 1930s. In 1932, inspired by these unemployed activists, jobless veterans took part in the famous “Bonus March” to Washington, D.C.

Also during 1932, one group organized a cooperative lumber mill and repair garage to provide jobs for the unemployed, while fresh food was secured for distribution among those who could not afford to purchase such goods. At least in part in response to these workers' agitations, the county relief board acted. In 1932, county funds for indigent relief, mother's pensions, and veteran's relief totaled $446,822, a full three times greater than the total of the previous year and a 560 percent growth from 1929. Workers also employed a variety of ingenious tactics to fend off starvation. Some pilfered food and supplies while others relied on the natural environment, digging clams at the beaches and poaching deer in the abundant Grays Harbor woods.

Building on their long-established radical traditions, workers directly challenged employers on the Grays Harbor docks and in its woods during the mid-1930s. Hoping to improve working conditions and recover some of the lost wages from the nearly decade-long depression, major strikes were waged by Hoquiam and Aberdeen maritime and lumber workers throughout 1934-1935. During the great lumber strike of 1935, somewhere between 6,000 and 10,000 workers marched between Aberdeen and Hoquiam on July 8, 1935, in a massive protest against the use of state troops to break the strike. In 1937, both the harbor longshoremen and lumber workers jumped to the newly organized Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), a federation of industrial unions, where they remained stalwart union militants for decades thereafter.

By the 1930s many of the wealthiest lumber barons were gone from the harbor, whether through death, debilitation, or relocation. Emerson died in 1914; Lytle followed in 1916. The Posey Manufacturing Company and Grays Harbor Commercial Company closed their doors in the early 1930s, although the former re-opened sometime later. After many business ventures considered by some to be questionable, lumberman-legislator Alex Polson was removed from his business responsibilities by the Merrill & Ring Corporation in 1931. C. E. "Stumpy" Payne, one of the founders of the IWW who came to Grays Harbor during the 1911-1912 free-speech fight, returned to the harbor two decades later and celebrated the departure of these men who "led pickhandle gangs against I.W.W.," noting: "The cash register tolls infrequently like a funeral bell" (Payne, “Clubbing Unionism”).

After the creation of the Works Progress Administration in 1935, Hoquiam became the site of several large public-works projects designed to infuse federal money into the local economy and provide jobs for unemployed workers. Significant among these projects was Olympic Stadium, a massive civic stadium that has housed semi-professional baseball teams, high school sports contests, and community events since its completion in 1938. In 2005, the stadium was filled by 10,000 spectators for the 100th installment of the Aberdeen-Hoquiam High School football contest, the oldest such rivalry in Washington state.

Hoquiam and the Decline of Logging

Federal environmental legislation during the 1980s and 1990s slowed logging on the Olympic Peninsula considerably. The crisis came to a head in 1990-1991 as the northern spotted owl was placed on the threatened species list, which led to the subsequent suspension of all logging on old-growth timber lands. Predictably, the environmental regulations took a terrible toll on residents of Grays Harbor County. As a single-industry town, Hoquiam had always been particularly susceptible to the economic vicissitudesof capitalist production.

Not surprisingly, many residents saw parallels with the earlier Great Depression. Small businesses and workers outside lumber, too, felt the squeeze of the industry’s decline, as was evidenced by the ubiquitous display of “This Family Supported by Timber Dollars” signs in the windows of homes and businesses and bumper stickers reading: “Hug a logger and you’ll never go back to trees” (Hughes and Beckwith, On the Harbor, 174; Hahn and Hahn, Spirited Passage, 155).

To protest the devastation to the local economy and their livelihoods, Hoquiam residents blended political with direct action, much as they had during previous crises. During the early 1990s, harborites regularly descended upon Olympia to have their voices heard by state legislators. Many of these men and women testified before legislative committees, and workers’ children could be seen carrying signs reading “What About My Future” and wearing “Support Your Local Logger” buttons (Hughes and Beckwith, On the Harbor, 176). On April 28, 1990, some 1,500 supporters of the timber industry blockaded the Riverside Bridge in Hoquiam, the only paved route west to the beaches and north along the west coast of the Olympic Peninsula.

As with the Great Depression, the economic hardship that befell the timber industry fell disproportionately on working people. While lumbermen and boss loggers took jobs in Seattle or adjusted their assets away from cutting trees, workers were left to suffer. At a forest conference held in Portland during April 1993, Hoquiam Mayor Phyllis Shrauger spoke for the town in telling President Bill Clinton: "It's too late for my city. In November we lost a three-mill complex. Unemployment is 19.5 percent and climbing" (Hughes and Beckwith, On the Harbor, 177).

Historic Hoquiam Today

Most of today's visitors experience Hoquiam as they head west to the ocean beaches or head north around the Pacific coast side of the Olympic Peninsula. Passersby might enjoy beautiful surrounding forests, a walk along the Hoquiam River, and the views of the breathtaking Olympic Mountains.

For those with an interest in Hoquiam's rich history, the town still has much to offer. Driving west through the town along Sumner Avenue, you find Olympic Stadium, the largest all-wood stadium still standing in the entire nation, two blocks to the north. Continue one mile west and stop by the Polson Museum, a National Historic Site named after one of the wealthiest lumber families in Washington history, and administered by its knowledgeable curator John Larson. For accommodations, stop at the Hoquiam Castle Bed and Breakfast, a gaudy mansion built for lumber baron Robert Lytle in 1900.

The 7th Street Theater, built in 1928, offers a variety of amateur and professional concerts and plays, and just next door you can find the 7th Street Deli and Sweet Shoppe, an old-time candy and soda shop, which features the longest continuously operated soda fountain in Western Washington.

Despite the economic troubles that have infected the region during the past three decades, Hoquiam has persisted with a population hovering around 9,000 residents and a slowly diversifying economy.

In August 2007, a Seattle-based biodiesel manufacturing plant, Imperium Renewables, opened its Imperium Grays Harbor plant on a stretch of land between Hoquiam and Aberdeen. Capable of producing more than 100 million gallons of biodiesel per year and employing approximately 60 workers, it is the largest such facility in the United States.

The Westport Shipyards operates a yacht-building facility in Hoquiam, and the Port of Grays Harbor continues to maintain facilities, including Bowerman Field (a small airport) and a port terminal, within the city's boundaries. More than 200 laborers earn wages at the Grays Harbor Paper mill facility, a plant originally built in 1929, closed down by ITT Rayonier in 1992, and revived by a group of local investors the next year. Grays Harbor Paper produces 100 percent recycled paper in a plant using logging waste for power.