Hoquiam Local No. 21 of the International Shingle Weavers' Union of America (ISWUA) was the lone stable source of unionism in the Grays Harbor lumber industry during the early part of the twentieth century. The union organized workers throughout Grays Harbor County, fought many strikes, and crafted unique cultural traditions based on union members' life and work in the shingle mills in the region. Local 21 was extraordinary in its size, in the degree of rank-and-file control over union affairs, and in the militancy of its members.

Shingle Weavers and their Union

The International Shingle Weavers’ Union of America was formed in January 1903 through the amalgamation of 24 local shingle weavers’ unions scattered around the United States. Concentrated mostly in Washington state, the largest lumber-producing region in the world, these locals were formed mostly between 1901 and 1903 by shingle sawyers, packers, and filers. Although the ISWUA was joined by other short-lived lumber unions in the Pacific Northwest before World War I, the weavers were the lone occupational group to maintain anything like a stable existence in the industry before the successes of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) in lumber during the 1910s.

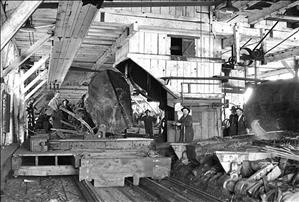

Shingle weavers were those laborers who grabbed the cut shingles and “weaved” them together into finished bundles. A journeyman weaver could handle 30,000 shingles in a 10-hour shift; boasts of more than 100,000 cut in a single day were common.

These jobs remained the province of men during the early twentieth century, although the rare woman, like the Elma union recording secretary, Mae Mason, also cut shingles in 1904. Shingle weaving was an extraordinarily dangerous occupation. The swirling saws and the speed at which operations were conducted led Cloice R. Howd to write: “Few men have sawn shingles for any length of time, particularly on an upright machine, without paying toll in a part or all of a hand” (Howd, 37).

Local 21

Many notable ISWUA locals emerged during the first decade of the twentieth century, including those at Everett, Bellingham, and Ballard. But Local 21 in Hoquiam was extraordinary for its size, for the degree of rank-and-file control over union affairs, and for the militancy of its members. Founded on September 11, 1902, Hoquiam Shingle Weavers’ Union No. 10,294 joined the Aberdeen shingle weavers’ local as one of the only two lumber unions on Grays Harbor. Both shingle weavers’ branches joined the ISWUA when it organized in January 1903, with the Hoquiam branch renamed as ISWUA Local 21. Shingle weavers’ unions were also founded around Grays Harbor in Elma in 1902, Cosmopolis in 1906, and Montesano in September 1907.

Between 1901 and 1907, Grays Harbor shingle weavers, in tandem with state organizers, organized nearly every shingle mill in Chehalis County. The lone significant holdout was the notorious Grays Harbor Commercial Company in Cosmopolis, whose hyper-exploitative labor practices earned it the ire of liberals and radicals alike, and gained it the nickname as the “Western Penitentiary” and a “scab-hatchery.”

Hoquiam and its sister cities of Aberdeen and Cosmopolis were frequently among the top shingle-producing centers in the nation. The Hoquiam Lumber and Shingle Company, owned by brothers Robert Lytle (1854-1916) and Joseph Lytle, could turn out 275 million shingles per year by 1906 and frequently ranked among the most productive mills in the nation.

Local 21 expanded from 49 members in good standing in June 1904 to 76 a year later. After the defeat of the ISWUA in a state-wide shingle strike in 1906, the Aberdeen local disbanded and its members joined Local 21. Through persistent agitation in the face of hostile employers, the newly expanded local grew in membership to 190 in September 1907 and to 250 in April 1908.

The Hoquiam Manifesto

Hoquiam contributed many prominent leaders and rank-and-file militants to the movement. Most notably, socialist J. G. Brown served multiple terms as delegate to the American Federation of Labor before being elected president of the ISWUA in January 1907.

In 1905, Brown and two other Local 21 members issued what became known as the “Hoquiam Manifesto,” a call for the ISWUA to organize the entire lumber industry, to support a socialist political program, and to divest the federation’s officials of some of their power in favor of rank-and-file control of the union. The controversy earned the Hoquiam radicals the condemnation of many fellow workers and nearly split the international union. “A. Shingleweaver” penned one of the many poetic answers to the Hoquiam weavers’ proposition:

Brown thinks that he can bulldoze,

The “Shingle Waving Craft,”

But the weavers all can understand,

That he is out for graft.

We know why he is working,

With such an earnest vim,

He wants to be the only fish,

In the unionistic swim.

He wants to be the President,

And Secretary, too;

And he would like to run the paper,

Just to tell what he can do.

For their continued advocacy of socialist politics and industrial unionism, Brown and his comrades were briefly barred from discussing politics within the

Shingle Weaver

, the house organ of the ISWUA. A year later the Hoquiam local acted on its own accord, and along with William Gohl of the Aberdeen Sailors’ Union of the Pacific, formed the Grays Harbor City Front Federation. According to Brown, the federation was a first step towards an industrial union, one that united all workers who labored along the waterfront into the same union.

"Hoquiam" Is Born

Hoquiam was the site of many union conventions during the early years of the twentieth century. During the 1906 ISWUA convention in Hoquiam, federation president Joseph Bolger received news that his wife had given birth to a daughter. So impressed by the hospitality demonstrated by his fellow workers, Bolger announced that he and his wife chose the name “Hoquiam” for the new addition to their family. In an act typical of the shingle weavers’ lively cultural traditions, Hoquiam weaver Jesse L. Havens commemorated the happy day with a poem:

At last it was settled that her name it should be

The same as the city on the shores of the sea --

An old Indian name, which old legends do say,

Belonged to a princess of a long ago day.

And so, Little Hoquiam, we toast your good health;

May your life always be one of sunshine and wealth,

And when older you grow, perhaps onward towards fame,

Remember the ones who gave you your name.

Large, Militant, and Strike-Prone

Because of their militant attitudes towards employers, large strike fund, and support within the community, the shingle weavers were the most strike-prone group in the lumber industry. Grays Harbor weavers struck no less than 10 times between 1902 and 1911. They carried out strikes over wages, piece rates, work hours, and control over the work process. Often these were “quickie strikes,” intended to surprise employers and force them into making concessions during profitable periods. In one such strike, weavers at the Hoquiam Lumber and Shingle Company mill spontaneously walked off the job after hearing that J. G. Brown had been fired because of his political commitments. After only a few days, mill manager Lytle retreated and the weavers returned to their posts.

Other strikes lasted many months, drained the union treasury, and forced the union to call upon a host of working-class allies throughout the community. In 1906, Grays Harbor weavers joined a state-wide general strike called to assist their fellow weavers in Ballard. One year earlier Local 21 successfully struck the Northwestern mill over a dispute involving their hospital fees. In late-1911, a weavers’ strike began at the Hoquiam Lumber and Shingle Company mill after manager Robert Lytle arbitrarily discharged his union employees. The conflict later snowballed into a massive lumber strike led by the Industrial Workers of the World that involved thousands of weavers, mill hands, and loggers throughout Western Washington.

Usually pushed into these strikes by employers reluctant to grant the eight-hour day or pass down a few pennies from their massive profits, the Hoquiam weavers won wage increases, hospital service for sick and injured workers, and reinstatement of members discharged for union membership. Testament to the wealth of the lumber barons can still be seen in Hoquiam. The massive homes of Robert Lytle and Alex Polson have been converted into a luxury bed and breakfast and museum respectively.

Poetry, Jokes, Manifestos, Funerals

Hoquiam shingle weavers also contributed to the vibrant working-class culture of early twentieth century Grays Harbor. They contributed poetry, jokes, manifestos, and philosophical tracts to the pages of the Shingle Weaver. The men also hosted mass meetings, dances, and sports matches. Each year the Hoquiam weavers took special pride in the elaborate floats crafted for Labor Day parades. These working-class cultural forms frequently took on explicitly oppositional politics, as they did during the 1906 Labor Day parade when Local 21 built a float depicting mill manager Lytle’s “bull pen,” a heavily fortified bunker where he had housed scabs during the shingle strike of that year.

Like many labor unions, the ISWUA held elaborate funeral rituals to pay tribute to their fallen fellow workers. These rights of passage were necessary to honor the victims of industrial slaughter, men like C. R. Wyman, a 26-year-old weaver who was sawed in half at the West and Slade mill in Aberdeen. Although numerous deaths did occur in the shingle mills, the greatest number of serious injuries were exacted on fingers and hands, in addition to which the sawdust-filled air caused cedar asthma, a respiratory disease common to shingle mill employees. During a single month in 1907, six Hoquiam weavers received serious cuts from the saws, and local president J. H. Cramer was forced to retire from the mills because of his respiratory ailment.

In November 1912, the AFL extended the jurisdiction of the shingle weavers to encompass the entire lumber industry. Two months later the union was renamed the International Union of Shingle Weavers, Sawmill Workers, and Woodsmen. After a precipitous membership decline beginning in 1914, and spurred on by a series of lost strikes in 1915, the AFL revoked the expanded union’s jurisdiction and re-established the ISWUA.

At the reorganized union’s first convention in April 1916, there were 24 unions functioning, including one in Aberdeen. Thereafter, the institutional base of the Grays Harbor shingle weavers rested in Aberdeen, although Hoquiam weavers continued to unionize and strike throughout the 1910s and 1920s.