The following articles, reprinted from 1914 issues of The Seattle Star, relate (with some inaccuracies) the story of the underground deaths of two coal miners, Andrew Churnick and Mike Babchanik. (The miners' names were actually Chernick and Babcanik, and Mike Babcanik was rather miraculously found alive seven days later.) It is also the story of a mistreated mine mule named Bess. Bess worked 24 hours a day without a rest at a Pacific Coal Co. coal mine in Franklin, in east King County. The revelation of the mule's condition came when a reporter went to the mine to cover the accident. The articles were contributed by William Kombol, Manager of Palmer Coking Coal Company located in Black Diamond (King County), Washington.

Reprinted from The Seattle Star, Thursday, February 19, 1914, p. 8

MULES ARE CHEAP; THEREFORE BESS KEEPS ON TOILING

By Fred L. Boalt

FRANKLIN, Feb. 19 -- There is no room in business for sentimental nonsense.

If you are to show a balance on the right side of the ledger, you cannot be over-careful of the lives of men or the comfort of mules.

Being a practical man, I am led to make these observations after visiting the Cannon mine, here, to find out how Andrew Churnick and Mike Vabcanick, experienced miners, died –– and why.

Viewed sentimentally, the disaster of last Monday was lamentable. One may feel sorry for men and mules that work in mines. But I cannot find that the Pacific Coast Coal Co. was in any way to be blamed for the tragedy.

Its business is to GET OUT THE COAL.

When I reached the mouth of the mine I met Toby, the Slav mule-skinner, and Bess, his mule.

Never have I seen such a ramshackle animal as this rack of bones. Her wobbly legs are swollen and bleeding. Her emaciated body is a mass of harness sores. Her mangy hide, stretched tight as a drumhead, shows every bone. Between bones are deep cavities where flesh ought to be. She had just strength enough left to drag the cars.

“Some Mule,” I observed.

Toby, the tow-headed, regarded his beast without pride.

“Bess he dam’ tired,” he said.

We talked. It seemed Bess was once a fine and prideful mule. Good mules cost money. Mule experts disagree as to which of two policies brings the best returns on an investment in mules.

Some say the better policy is to feed a mule well, and work it reasonable hours, for then it will live long.

But the Pacific Coast Coal Co. has found that mules are tough and hard to kill, and that if you work a mule 24 hours a day, it will, while it lasts, do the work of three mules working eight-hour shifts.

Bess, Toby told me, had worked four months, 24 hour shifts! It’s hard to believe that even a mule could stand it. And on a diet of hay at that!

Toby said Bess snatched ten-minute naps, STANDING UP, between trips!

When Bess dies, the company will buy another mule.

So much for Bess, who isn’t worth bothering about, anyhow.

Men are different. For one thing, men are not property. They work for wages. If they don’t like the job and the attendant risks, they are at liberty to quit.

Clearly, it is the right of a coal company to get out as much coal as possible, as cheaply as possible, and to sell it for as much money as possible.

Therefore, the company, knowing there was coal at the face of No. 11 chute, was justified in telling Andrew Churnick and Mike Babchanik to go there and dig it.

It is true that No. 11 chute was known to be dangerous. For a month the water had been pouring through, and the earth above had been cracking and groaning like a live thing in pain.

It is known, too, that the chute’s face was perilously near the earth’s surface, and that there was gravel, which miners fear as they fear quicksand, ahead.

The company didn’t know that just above the chute was a bog –– a natural catch-basin which drained the hills all about. The company could have known this if it had cared to survey. But surveys cost money.

The flow of water increased until one stream was the size of a man’s arm. The force of the flow over the inclined floor of the chute was sufficient to flush the coal as fast as it was dug down to the gangway, 400 feet away.

This, incidentally, saved the cost of a “bucker,"whose duty it is to “buck” the coal down the incline to where it can be picked up by the cars.

So Churnick and Babchanik approached the chute in fear. But a job’s a job. And $3.80 A DAY WAS ALL THAT STOOD BETWEEN THEIR FAMILIES AND STARVATION.

If you had been on a certain forest trail a mile distant from the mine mouth at 9 o’clock Monday morning, at a point where the road overlooks a natural basin, you could have witnessed what appeared to be a strange and awful phenomenon.

The bottom fell out of the basin. Huge trees tottered and crashed down, and were sucked into the abyss. There was a roar of rushing waters, a crushing, crunching, grinding chorus, and then silence.

At that instant two lives were blotted out in the unseen warren below.

From the still forest trail you could not guess what was happening in the bowels of the earth beneath your feet.

Thousands of tons of water and gravel and boulders and quicksand rushed down into the chute. I think old Earth tried to warn the miners. For this morning the rescue party found the crushed and mangled body of a man, not in No. 11, but in No. 12.

He had run for his life.

The flood caught him and his comrade before they had gotten far, and made short work of them. It swept over them. It roared through the cross-cuts. The miners fled before it, snatching at their heels as they fled from cross-cut to cross-cut, from chute to chute, dodging and twisting in that underground labyrinth, seeking an avenue of escape.

Only the bulkheads at the bottom of the chutes held the flood out of the gangway long enough for the miners to get away.

No coal is coming out of the mine today. Only gravel and muck.

But, coal or muck, there is no rest for Bess.

“Hard luck,” said Superintendent of Mines, William Hann.

“It is not my business to fix the responsibility,” said State Mine Inspector, James Bagley.

“If,” said an old miner, “the company had obeyed the law and made test borings, the water and gravel would have been discovered, and Mike and Andy would be alive today.”

The state will pay the widows $4,000 each and wash its hands of the whole business.

The company may do something handsome in the way of funeral expenses.

The Seattle Star, Friday, February 20, 1914, p. 1

County Humane Society to Aid Bess, the Mule

The King County Humane society promises to put an end to the practice of the Pacific Coast Coal Co., which has found that by working mules in its mines continually without a rest until they die, more work can be accomplished than by working the animals in shifts.

Fred L. Boalt, special writer for The Star, found such a condition upon arriving in Franklin, Wash., to “cover” an accident in the Cannon coal mine.

The story appeared in Thursday’s Star; and, acting immediately, the humane society assigned Officer Vaupel and Mrs. S. A. Hollabaugh to investigate.

The Seattle Star, Wednesday, February 25, 1914, p. 1

HUMANE AGENT RESCUES BESS; TO MAKE ARREST

“Bess,” the mule which worked 24 hours a day in the Pacific Coast Coal Co.’s mine at Franklin, Wash., is enjoying a much-needed rest today as a result of prompt action by the King County Humane society, following publication of an article regarding her in The Star.

An arrest will be made at the mine today, as a consequence.

Fred L. Boalt, The Star’s special writer discovered “Bess” while “covering” a mine accident at Franklin. He found that the company worked its mules until they die; instead of getting more and working them in shifts. It was cheaper.

Mrs. S. C. Griggs, secretary of the Humane society, visited the mine with two officers Friday. She immediately ordered Bess to the barn.

“The mule had worked two weeks without a rest,” Mrs. Griggs said.

Postscript:

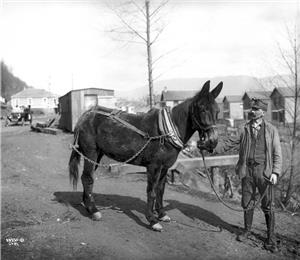

On St. Patrick’s Day, 1914, the Pacific Coast Coal Company hired the famed photographer Asahel Curtis, who had teamed up with William Miller in the firm Curtis and Miller, to take three photos of “Bess” the mule. The photos were shot in the town of Franklin not far from the mine. They were likely taken in order to dispel any remaining public concerns as to the ultimate fate of “Bess.”

Poem

(Reprinted from The Seattle Star, March 21, 1914, p. 4)

THE MULE

by Berton Braley

You couldn't call the mule "a beaut,"

However much you boast of him.

For pulchritude is not his suit,

To say the very most of him;

His disposition, too, is not especially commendable.

And, though he'll often stand a lot,

His temper's undependable.

He's hard of mouth and obstinate;

Acquaintance soon reveals of him,

That it is sometimes tempting fate,

To get too near the heels of him;

And when he lays those long ears back,

No beating or reproving him,

Will ever stir him from his track,

Until the spirit's moving him.

And yet -- and yet the mule will thrive,

And labor with agility,

Where horses cannot keep alive,

But die with great facility;

His treatment frequently is rough,

But he is quite resigned to it,

And he can toil with vim enough,

When he makes up his mind to it!

Not always is a heavy stick,

The most effective charm to him,

For, though his muleship's hide is thick,

Good usage does no harm to him;

So look on him with kindly eye,

And you will not repent of it;

His market price is very high,

And he's worth every cent of it!

Historical Note

Concerning the character of a mule (from a post card from a Wallace, Idaho, mining museum):

"Being a dependable, intelligent and hard working animal the mule was particularly well suited to hauling in the mine. They quickly learned the haulage level and their job, making reins unnecessary. These hardy animals sometimes stayed underground for up to eight years. They have now been replaced by battery powered locomotives sometimes referred to as 'Electric Mules.'"