James Bertrand was one of northern Whatcom County’s earliest settlers. He was there not only during many key moments in the county’s early history, but also during key moments in the early history of British Columbia’s Lower Mainland. A nineteenth-century everyman, Bertrand made a wide mark throughout the area, and landmarks both in Washington state and British Columbia still carry his name today.

A Keen Eye

James Curtis (some accounts say “Curtiss”) Bertrand was born on September 2, 1829, in Exeter, Illinois. Bertrand, known as both “James” and “Jim,” made his first trip to the West in 1850, traveling to California with a “five-yoke team of oxen” (“Man, 103...”) on a journey lasting four months and 16 days. He made at least one additional overland trip during the 1850s, and by 1857 was living in Mokelumne Hill, California, one of the richest -- and rowdiest -- gold mining towns in the state.

But by the late 1850s much of the area’s gold was gone. Bertrand packed his bags and headed north, arriving in Whatcom (now [2011] part of Bellingham) on July 2, 1858. He headed north to the border that was then being marked between the United States and British North America (there would be no “Canada” until 1867) by teams of American and British men as part of the work of the International Boundary Commission. He signed up for a position on the American team, but was rejected. He then landed a spot on the British team as an axman, and later recounted that he cut trees for 11 months without missing a day.

Bertrand had a keen eye and a good memory. In December 1889 he shared the area’s early history in two articles in the Blaine Journal, and discussed his adventures working for the International Boundary Commission. He complained that members of the American team ransacked his house while he was away one day, taking what they wanted and breaking what they didn’t. He also reported that smuggling was rampant by both teams, with the Americans sneaking liquor to the British, and the British smuggling beef to the Americans.

Bertrand witnessed the early days of New Westminster, British Columbia, the oldest city in western Canada, and first capital of British Columbia. But he had a bigger impact farther east in the British Columbia town of Chilliwack. As the ax team moved through the area east of Sumas in 1859, Bertrand fell in love with a Native girl living in Chilliwack, Mary Ann (O-See-Ah-Mee-Ah) Soowhalie (1845?-1918). Her family is said not to have approved of Bertrand at first. One account says her brothers threatened to kill him on sight, and he was forced to hide out and live on food smuggled to him by his bride-to-be until the family relented. They were married in Chilliwack on November 3, 1859, and had 11 children: William (1861-1930), Charles (1863-1934), Samuel (1865-1888), Annie (1867-1953), Laura (1868-?), Henry (1870-1940), Josephine (1877-1952), Thomas (1878-1918), Sara (1881-1953), James Jr. (1884-1940), and Elsie (1886-?).

Canadian and American

Bertrand arrived in Chilliwack during the height of the Fraser River Gold Rush in southwestern British Columbia. It waned soon after, but he stayed on. He opened a store in the community and played an active role in the happenings of the young settlement for a dozen years. In 1863 he preempted land with an associate, Reuben Nowell, in what is now the eastern part of downtown Chilliwack, and later had a cattle farm on Chilliwack Prairie. Bertrand is also credited for putting the “whack” in the name of the town of Chilliwhack (now Chilliwack); its original spelling had been Chilukweyuk.

In 1871 Bertrand and his family returned to American soil, albeit just barely. While helping mark the boundary Bertrand had discovered a small prairie of grass and forests, perhaps a mile or two on the American side of the border, running along a creek. In 1871 he built a house at the site, located about three miles northwest of present-day Lynden, and the family lived there for 15 years. Both the creek (which actually has just under half of its 21-mile length in the United States, with the rest in Canada) and the prairie were named after Bertrand. Here he and his family spent much of their time hunting and trapping. The prairie was full of wildlife, and the Bertrands hunted and trapped beaver, bear, bobcat, cougar, and mink, using some of the furs as barter for groceries at Enoch Hawley’s store in Lynden.

Almost everyone in the Nooksack Valley knew the Bertrands. When Phoebe Judson took up donations in the spring of 1876 to hire someone to clear the three-quarter-mile-long log jam on the Nooksack River near Ferndale, Bertrand contributed to the fund. When Enoch Hawley (1821-1889) built a new store in Lynden in 1882, Bertrand and his son Bill were on the ax crew that cut trees for it. As Lynden continued to grow during the 1880s, he was a regular contributor to public improvements.

In 1886 the family moved to Blaine, and Bertrand quickly made his mark there. He opened a general store on E Street (today’s Marine Drive), near the wharf. In 1887 the store became the site of Blaine’s first telegraph office. He built three more buildings in Blaine during 1887 and 1888, and one of these buildings served as Blaine’s customs office for a brief period. He also dabbled briefly in real estate and in the hotel business in Blaine during the late 1880s. When the town first incorporated in 1890, Bertrand signed the petition for incorporation.

A Long and Winding Legacy

In 1891 Daniel Drysdale bought a cannery at Semiahmoo (later bought by the Alaska Packers Association), and hired Bertrand as an interpreter to buy salmon from the local Native Americans. He was stationed at Point Roberts for this particular gig. Sometime after that he made his way north to Alaska and later explored northern British Columbia. He eventually returned to Blaine, and enjoyed good health and a remarkably long life; he remained active past his 100th birthday, and spent at least part of each day cutting wood. He was a well-known and well-liked figure throughout northern Whatcom County.

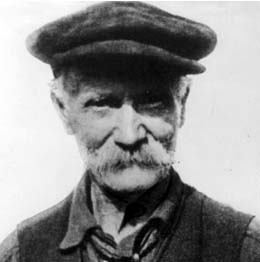

An interview and photograph of Bertrand appear in the September 8, 1932, Seattle Times, when he joined the First Voters League in Blaine. (This was more of a joke for Bertrand, because most of the league’s members were 21 years old and voting for the first time.) He comments in the article about the then-current state of affairs as the country spiraled into the depths of the Great Depression, asserting, “The nation needs young men who can get us out of the rut some of the old fellows got us into” (“Man, 103...”) and allowed that he intended to vote Republican in the primary the following week.

It turned out that 1932 was Bertrand’s last election. He caught a cold and died at the home of his son, identified in his obituary as “Jenks” (James Jr.?) Bertrand, on February 13, 1933, leaving a long and winding legacy that lives on today.