William Shelton (1868-1938), cultural leader of the Tulalip Tribes, spent much of his life attempting to bridge the divide between regional Indians and whites through traditional storytelling and art. Shelton gained an understanding of his own native culture through family teachings and by learning from many of his tribal elders. He also was adept at working with Bureau of Indian Affairs and city government officials, gaining their respect and support. Shelton spent years mastering the art of wood carving in order to create story poles through which he shared many of his tribes’ cultural teachings. To accompany one of his carved poles, Shelton wrote a booklet published in 1913 titled Indian Totem Legends which told the stories of the pole’s carved figures. The booklet also carried the author’s autobiography. On January 2, 1914, a longer version of this same piece was published in The Everett Daily Herald. The narrative that follows is Shelton’s full 1914 Daily Herald version. It is a reprint of "Maker of Tulalip Totem Pole Tells Story of His Life," The Everett Daily Herald, January 2, 1914, p. 1. --Margaret Riddle

Maker of Tulalip Totem Pole Tells Story of His Life By William Shelton

I am an Indian of 45 years past. I am of Snohomish, part Skay-whah-mish, Puyallup and Wenatchee tribes. I was raised by my parents on the Tulalip Reservation, Washington, and taught the Indian schooling advices of the Indian race by my father and mother and some old uncles and grand uncles of mine. They wanted me to grow up a big, smart Indian, to be able to talk and lead my people. They taught me to be a big Indian doctor until I was 17 years old, when I began to change my mind. During all that time I was taught the old Indian ways. Finally I made up my mind to go to the Tulalip Mission School run by priests and sisters. I thought to myself that maybe sometimes we will need the white people’s education and it might be a good thing to learn a little of the white race before I became a man. So I went to school when I was 18 years old. I stayed in the Mission School until I was 21 years old. Then I got married. Very little education I learned just enough to read a little and to understand the English language. I found a difference between our schooling and the English at that time, so I used both the schooling I had in Indian and English.

Two years after I got married I was recommended by two good friends of mine, Dr. Ed. Buchanan and William McCluskey, so I had a position in the government work. I was appointed as sawyer at the old mill at Tulalip Agency and I found it awfully nice to be with good white people and friends. I soon got so I could run a saw and turn out lumber. I learned to do repairing, learning every day how to file saws and run machinery without ruining any part of it.

Then I got so I could do most anything. I got so I could do carpenter work, millwrighting and a little of everything. Then, after that, I worked under two or three different agents who encouraged me right along to do the work. I am using both the Indian people’s and the white people’s languages and I get along very nicely on both sides. I got so I could handle my people and I got so I could get along with my good friends -- the white people -- all by trying and doing all I can in my work. I got so I could look back and see my grandfathers and grandmothers and the old people who are now fast disappearing; that used to tell me how to be good and take care of the old people and help them along and to be good to everybody. I got so I could see that the white people’s advice was pretty near the same thing as the Indians’ and that I must try to do my work right; not to cheat, but to be square and try to get along.

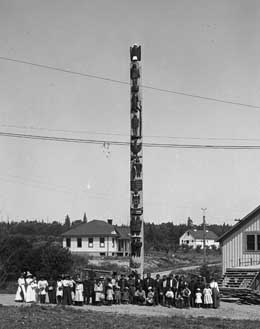

I saw right there that the two races were pretty near alike, only that in the first place our people don’t understand the English language and the ruling of the good friends, the white people. There is a broken link between my race and the white people. So I thought I better look back and talk to the older people that are living and try to explain our history by getting their totems and carve them out on the pole like the way it used to be years ago. So I went around gathering the old Indians and talking to them in the genuine Indian language that I learned when I was young. I used a nice language to them to make them understand why I wanted their totems carved on the pole to show our history -- so our good friends would see the ruling foundation of all Indians around the Sound.

We had a regular meeting and the members of the different tribes talked about the totems that were going to be carved on the pole. The old friends of mine understood and each one of them got up and made a speech, telling how nice it was going to be to have their totems carved out so the people would see the Indian beliefs. It shows from the pole that they understood, and shows that they had good sense to be willing to do that, for that is the best we could do, as it would show out so everybody could see. That is how you can see the totem pole that I carved out with the courage of the older Indians that are living, to show our young children that are now in school who never saw anything like that before, for these totems and medicine men have been dropped for several years. They are never seen, for the Indians thought that the best they could do was to drop all their ways or else never get along with the white people. That was their belief. But I am glad that we have a little of the Indian history and have carved it out on the pole to show a little of the Indian belief.

Really, I ought to be a big Indian medicine man, but I was a failure. At the same time I knew how to get along in the Indian race and I got so I could get along nicely with the white race, all by the courage of a good friend of mine, Dr. Charles Buchanan, our present superintendent. He handles me something like the way my father used to handle me when I was a boy. There were many times when the doctor told me to go ahead and do a work that I had never seen before and never had before, but he’ll tell me to go ahead and do it and say “I know I can.” At first I thought that I wouldn’t be able to put it up, such as the mill, but he told me to go ahead and put it up. So I started in and got it up as he said. The mill is sawing lumber and turning out the kind of lumber needed. That is why I say he handles me something like my father, for when I was a boy my father always told me to go ahead and do what I was told and I would become a man.

There were many, many times that my father told me to go out to a certain place at night when all was dark and you couldn’t see hardly anything, but I dare not say I couldn’t get there. It had to be done when he mentioned the place where I was to go. I must get there through the dark, even though cold and naked. He used to give me a stick -- a home stick they used to call it, a little stick that is known by everyone around home -- for me to carry and leave at the place or point mentioned to prove that I got there. I had that to carry many times in different places.

The hardest time I had was at the Straits between Port Angeles and Neah Bay Reservation. My father sent me out late in the evening while everybody was asleep. I slept with an old man by the name of William Weallup. The rule was that if I should go out, I must go quietly so nobody would know that I left the house. It was against the Indian ruling for a boy or any young man going out at night to make any noise. So I slipped away from the old man that I slept with and left the house without anyone knowing that I was out. I traveled fully a half mile on the mountain side that leads right down to the salt water where there were barnacles on all the stones and all strange places, but I was told to go to a certain place and get there, so I did. The tide was high so I had to swim around those sharp rocks in the cold water to get to the place that I was told to reach. This happened when I was 12 years old and was the hardest place I ever got to. The idea of my father was for me to find a strong totem that would make me a brave, smart man; that’s what he wanted me to be. But I believe that even if I had learned a strong totem at the time, I wouldn’t use it now, for it is a thing that couldn’t get along with the white race law.

What I mean by saying that I am a failure to my race is that I never use my Indian training as much as I ought to. I am going more by the white people’s advice than by the Indian advice nowadays and I believe that we all should learn so we could work like the white people in some days that are coming. I believe that it is a good example for the young children that are growing up to see my work and to read my history for I am poor, I ain’t got any education, but very little of the white people’s schooling, but it shows that we could learn and do things like our friends if we wanted to. And it shows right here that we need the courage to learn, for that is all that carries me along -- the courage of my good friends. Without that it is easy to slip back into the old Indian ways. I hope that we will have the courage all the time to be able to be with our good friends, some day that is coming.