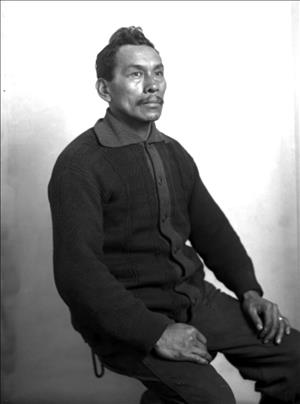

Storyteller, wood carver, teacher, and Tulalip cultural leader, William Shelton Wha-cah-dub, Whea-kadim earned great respect in his lifetime from both Indians and whites -- the two cultures that he loved and sought to bring together -- and was a key figure in the preservation of Coast Salish culture. Gaining permission from the U.S. government to carve a story pole in 1912, Shelton collected Lushootseed sklaletut stories from many regional tribal elders and carved pole figures representing many of their stories. In his lifetime, he carved four story poles and published these stories in book format. In the 1920s and 1930s William Shelton was a sought-after performer for club meetings, school classes, fairs, and regional radio where he became a spokesman for American Indian culture, often dressing in Great Plains ceremonial garb complete with feathered headdress, clothing he claimed would be most easily recognized as Indian. Shelton's title of chief was as Tulalip Chief of Police but his works made him a cultural leader. So important was he to the preservation of Tulalip tribal tradition that upon his death, many feared the culture would vanish with him. Instead his accomplishments served as the bridge for following generations who found new ways to continue his work.

Bridging Two Cultures

By the time William Shelton was born, Coast Salish cultural tradition had been nearly destroyed by white contact. Disease had decimated tribal populations and, following the Point Elliott Treaty of 1855 that placed natives on reservations, attempts at assimilating local tribes into the main culture led to cultural genocide. Natives were forbidden to speak their language and practice tribal customs at Indian boarding schools. Greatly fearing this loss, William Shelton spent his entire life gathering, preserving and sharing the remaining traditions still in the memories of his own family and regional tribal elders.

William Shelton Wha-cah-dub, Whea-kadim was born on July 4, 1868, at Sandy Point, Whidbey Island, to Charles (d. 1898) and Sus-chol-cho-lit-so Whea kadim. Shelton was of Snohomish, Skay-whah-mish, Puyallup, and Wenatchee ancestry; his father was born on the Skykomish River and his mother in the Hibolb village, now the northern tip of Everett. Continuing to honor their tribal beliefs, Shelton’s family taught their son the native ways, hoping he would one day become a tribal leader and "Indian doctor" (Everett Daily Herald, January 2, 1914). They did not send young William to the Tulalip Indian boarding school.

But about age 17 William ran away from home and enrolled himself in the Tulalip Mission School in order to learn the English language and culture. Thus began Shelton’s lifetime work of cultural comparison and his attempt to bring together his own Indian heritage and the teachings of his white teachers. Shelton insisted that the native stories were basically instructional guideposts for the young, not religious, and therefore much like the stories of non-Indians.

Shelton was a bright student and showed good vocational skills. He was soon allowed to run the saw and turn out lumber in the old Tulalip mill. Shelton began the art of wood carving. It was at this time that he married Ruth Sehome Shelton who bore him three children, Robert (1891-1930), Ruth (1902-1917) and Harriette (1904-1991).

The native longhouse had long been the center of tribal community and Shelton decided to build one as well as a story pole, but to do this he needed government approval. Tulalip Indian agent Dr. Charles Milton Buchanan (1868-1920) told Shelton to write to the Secretary of the Interior. Shelton gained permission, a decided softening of Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) policy. In an interview by Lawrence David Rygg with Shelton's daughter Harriette Shelton Dover, she recalled her father's story.

"He said, 'We will not make many totem poles. We will put all these sklaletuts, these guiding spirits, on one pole.' Months later he got an answer. The answer came to the agent and it said, 'William Shelton, you can go ahead, but just don’t allow the Indians to revert back too much to old days.' My father went to La Conner and he called a meeting. He talked with all the old elderly people and told them what he had in mind. Each one told him what their vision was when they were young. Their visions were a whale, two women, a man or strange animal of some kind. Each one sang their song in the long house that my father built in 1913.

"The Indian men talked. They cried tears remembering the old days. One man sang his song. It was the first time he’d sung that song for about thirty years, more, fifty years. The drums beat and he had eagle feathers that went up, they’re split. He had a whole lot of white down. When he came out it followed him like a cloud. The floor was already covered with down. The dancers would go around that down and sing a certain song for the blessing of the earth" (Rygg, 1977).

The Longhouse and the Story Poles

Selecting a 60-foot cedar log measuring four feet in diameter at its base, William Shelton began carving his first story pole late in 1912. He carved representational sklaletut figures carved on both sides of the pole, working first with an axe and refining with hand tools. Elders contributing stories represented various Lushootseed-speaking tribes -- some were Skagit, some Snohomish. Many had been reluctant at first to recall the old days, but Shelton was persuasive.

Shelton and student apprentices from the Tulalip Indian School carved the pole, which was scheduled for placement in front of the school. When they attempted to raise the pole in May 1913, it fell to the ground and was severely damaged, making repairs necessary before final placement later that year. The BIA requested that Shelton write stories of these pole figures and the stories were published in 1914 as Indian Totem Legends of the North West Coast Country by one of the Indians. The pole remained at the school location until the 1960s. By that time, the mid-section had rotted and the pole was cut in half, the upper portion replaced at the school site and the remainder of the pole displayed in segments.

The new Tulalip longhouse was completed in 1913 and used for the Treaty Day celebrations held on January 22, 1914. Photographer John Juleen of Everett shot a series of views that day. Poles supporting the structure can be seen with carved and painted figures.

The success of Shelton's first story pole led Everett residents to commission a pole. Everett school children and service groups helped raise money for an Everett pole, which was erected in front of Redman's Hall at the corner California Avenue and Wetmore Avenue with an official dedication service on July 26, 1922, in honor of Chief Patkanim (ca. 1808-1858), the Snoqualmie chief who signed the Point Elliott Treaty for the Snohomish and other tribes. A new version of the story pole stories was published

In 1929 the pole officially was given to the City of Everett and it was moved to the Pacific Highway (now Evergreen Way) and 44th Street, Everett city limits at that time. Over the decades, city limit boundaries extended and the pole deteriorated. By the 1990s it was badly in need of repair and in 1996 the Everett City Council approved $12,000 for its restoration. The Everett Parks and Recreation Department recommended that it be placed in a better location where it could be protected and more easily seen by the public. The Tulalip Tribes were involved in discussions about the proper placement and two locations were considered, Everett's Legion Park and Grand Avenue Park. Restoration was done and the pole taken down but to date (2009) it is still not available for public viewing.

Shelton's visibility led others to commission his work and in October 1935 a 37-foot Shelton pole was placed in Krape Park in Freeport, Illinois, by the U.S. Council of Boy Scouts. Copies of Legends of the Totem Pole were also sent for the Freeport Public Library and schools.

Washington Governor Roland Hartley (1864-1952) of Everett requested the creation of a William Shelton pole on the capitol grounds in Olympia. Washington State school children raised money for the project, which was supported by the Snohomish County Parent-Teacher-Association (PTA). Hartley selected the cedar tree to be used and Shelton worked for the next five years carving the pole. He died before its completion and other tribal carvers finished the work. The pole was dedicated on May 14, 1940. This pole has received good care and maintenance since that time, being repainted in the early 1950s and in 1962. In 1974 and 1987, it underwent major restoration when it was pressure-washed, sanded, caulked, and repainted. More maintenance was done in 1997. But in 2010 concern that, due to rot, the pole had become a safety hazard led to it being taken down and stored on Capitol grounds until a new place could be found for its care and display. The cultural stories are lasting, but the wood is not.

Shelton's Legacy

William Shelton died of pneumonia February 11, 1938, in Everett. He was buried in Mission Beach Cemetery at Tulalip only four years after the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 began to allow tribal self-government. Although his contributions to the preservation of Native American culture were prominently listed in his obituaries, Shelton was also applauded for his work with the Tulalip Tribes in translating and negotiating the sale of timber from reservation land and for his work in raising World War I war bonds from the tribes.

Accompanying his obituary, the Everett Daily Herald ran a photograph taken of Shelton in Indian dress, eating strawberry shortcake at the Marysville Strawberry festival the previous year. William Shelton's work had been to unite his native people with non-Indians and, in his own words, this sometimes meant yielding to necessary compromises. His efforts preserved Lushootseed stories and art and he inspired a generation of younger tribal leaders to build on this tradition. A recent gift to the Tulalip Hibulb Cultural Center is a small carving by Shelton which has now been cleaned and restored and is ready to take its place in the Center when it opens in 2009.