From July 22 to 31, 1811, Canadian explorer David Thompson (1770-1857) ascends the lower Columbia River, accompanied by members of the Pacific Fur Company of New York, who have just established a post called Astoria near the mouth of the Columbia. Thompson, the fur agent in charge of the Columbia Department of the North West Company of Canada, has recently descended the Columbia from Kettle Falls, thereby determining that the river is navigable to the sea and that it will provide a viable trade route between the Pacific, the Inland Northwest, and Canada. Following his arrival at Astoria, Thompson and officials of the American company have negotiated a tentative arrangement for sharing the trade of the Columbia District.

July 22: Off for the Interior

“July 22, Monday. A fine day. Arranged for setting off for the Interior ... . I pray Kind Providence to send us a good journey to my Family and Friends. At 1:24 PM set off” (Belyea, 157).

After a week’s sojourn at the mouth of the Columbia, David Thompson and his crew of Iroquois and French Canadians departed Astoria in company with David Stuart and eight men of the Pacific Fur Company, who were planning to establish a trading post somewhere upriver. The Americans had decided to travel upstream in company with the Nor’Westers "for the sake of mutual protection and safety, our party being too small to attempt anything of the kind by itself" (Ross, 115). Two Kootenai Indians who had arrived on the coast a month earlier rode along with the American party.

According to Alexander Ross, he and the two other clerks in the American party embarked in style: "After our canoes were laden, we moved down to the water’s edge -- one with a cloak on his arm, another with his umbrella, a third with pamphlets and newspapers for amusement, preparing, as we thought, for a trip of pleasure" (Ross, 116). The Astorians had purchased two dugout canoes from the local Chinook Indians, and the heavy boats proved "fickle" to paddlers accustomed to lighter craft. Loaded with more than a ton of trade goods, the dugouts began to take on water and soon ran ashore on the rocks of Tongue Point. The men lugged baggage and boats across the narrow isthmus to the other side, where they met Thompson’s men, who had successfully negotiated the point in their cedar plank canoe.

The Astorians reloaded and made a few more miles before a sandbar arrested their boat.

"Down came the mast, sail, and rigging about our ears ... cloaks and umbrellas, so gay in the morning, were now thrown aside for the paddle and carrying strap, and the pamphlets and newspapers went to the bottom" (Ross, 117).

July 23: A Very Steep Shore

Moving slowly against the current, with a sail to take advantage of the upriver wind, Thompson kept an eye on the volcanic cones of Mounts Rainier, St. Helens, and Hood as he carefully recorded the river courses in his notebook.

The two parties made better progress on the second day, but as evening came on, they couldn’t find a place to camp, for the high runoff had flooded the lowlands along both sides of the river. They finally pulled ashore "on a very steep Shore, we put up; with difficulty we could place the Goods, & all slept as I may say standing" (Belyea, 158). Alexander Ross, not as accustomed to uncomfortable campsites as the surveyor, wrote that "we passed a gloomy night -- drenched with wet, without fire, without supper, and without sleep" (Ross, 117).

July 24: Cowlitz River to Willamette River

"July 24 Wednesday. A cloudy musketoe Morning" (Belyea, 158). Shortly after leaving camp, the parties noticed a rocky precipice near present-day Longview on the north shore of the river: "all over this rock -- top, sides, and bottom -- were placed canoes of all sorts and sizes, containing relics of the dead, the congregated dust of many ages" (Ross, 117). This burial site, known to white traders as Mount Coffin, was situated just downstream from the mouth of the Cowlitz River.

A few miles upstream, the paddlers passed another tribal cemetery on Coffin Rock, "an isolated rock, covered also with canoes and dead bodies. This sepulchral rock has a ghastly appearance, in the middle of the stream, and we rowed by it in silence" (Ross, 118). Toward evening, Thompson spotted the wide mouth of the "Wil ar bet" (Willamette) River and put ashore to camp.

July 25: Willamette River to Point Vancouver

After traversing the broad delta of the Willamette, the Nor'Westers and Astorians passed eight tribal canoes manned by fishermen seining with long nets who were pulling in ten or more salmon with each haul. The white men attempted to procure some fresh fish, but had no success. That evening, camped in a meadow just downstream from Point Vancouver, Thompson was able to purchase split salmon from a nearby Indian camp "for Rings, Bells, Buttons & Tobacco" (Belyea, 159).

July 26 – 27: The Gorge

"A chain of huge black rocks rose perpendicularly from the water's edge ... hemmed in by these rocky heights, the current assumed double force, so that our paddles proved almost ineffectual" (Ross, 119).

Late in the second afternoon of hard paddling, Thompson alerted David Stuart that they needed to stop for the evening as they were approaching the foot of the "great Rapid" or Cascades of the Columbia (present site of Bonneville Dam). Leaving behind the wide meadows and low islands of the lower river, the canoes were now entering the Columbia Gorge.

The parties had just made camp when a canoe carrying a blind chief from a nearby village arrived for a smoke. As they were passing the pipe, two more canoes paddled by; David Stuart called out and asked if they would bring back some salmon, to which they agreed. When they never returned, Thompson, who had noticed unfriendly looks from other canoes they had encountered during the day, began to worry. "I suspected something wrong, and we kept ourselves ready to act as circumstances may require," he wrote (Thompson, Travels, ii.251). That evening he kept the canoes loaded and ready to shove off, but the night passed quietly.

July 28: Cascades of the Columbia

On the morning of July 28th, the two parties had proceeded about a half mile when they spotted four fishermen on shore and stopped to purchase a batch of fresh salmon for breakfast. Here Thompson learned the cause of the unfriendly looks from the day before.

"The four men addressed me; saying ... is it true that the white men, (looking at Mr Stuart and his Men) have brought with them the Small Pox to destroy us; and also two men of enormous size, who are on their way to us, overturning the Ground, and burying all the Villages and Lodges underneath it; is this true and are we all soon to die?" (Thompson, Travels, iii.283).

Thompson assured them that there was no truth whatsoever to either rumor, "at which they appeared much pleased" (Thompson, Travels, iii.283).

Apparently the Kootenai couple who were traveling with the Astorians, had made certain prophesies on their way downstream two months earlier about the advent of giants and of white men bearing the dreaded smallpox, which had decimated tribes along the Columbia less than a decade earlier. After quelling the rumor, Thompson observed: "had not the Kootanae been under our immediate care she would have been killed for the lies she told on her way to the Sea” (Belyea, 160).

With breakfast concluded and the Kootenai couple safe for the moment, the men faced up to the long portage around the boisterous flume of the Cascades rapids.

"We examined the road over which we had to transport the goods, and found it to be 1450 yards long ... with up-hills, down-hills, and side-hills, most of the way, besides a confusion of rocks, gullies, and thick woods, from end to end" (Ross, 122).

Thompson’s seven voyageurs had no problem scurrying over the path with their minimal load, but the Astorians, who were carrying a year's supply of trade goods and supplies in addition to the heavy dugout canoes, needed extra manpower. Stuart hired several men from the nearby village to help, and by midafternoon all the cargo was across the portage. As the porters gathered around to be paid, so did a number of men who had served only as spectators. Stuart could not distinguish those who had helped from those who had not. "Much Tobacco was given, yet the Indians were highly discontented; they all appeared with their 2 pointed Daggers, and surrounded us on the land side, their appearance very menacing” (Belyea, 161).

The Nor’Westers had already carried their canoe to the top of the rapids, but Stuarts' dugouts were still at the lower end. These were too heavy to carry, and none of the local men would help drag them across until Stuart promised them better pay. Thompson “spoke to the Chiefs of the hard usage they gave Mr. Stuart, & reasoning with them, they sent off all the young Men” (Belyea, 161). As soon as Stuart’s boats arrived, the two parties paddled upstream a short distance to camp.

July 29 – 31: The Cascades to the Dalles

Two relatively uneventful days brought the furmen to the river's next obstacle, a series of rapids which the voyageurs dubbed the Dalles (now buried by the Dalles dam, near the city of The Dalles, Oregon). The Nor'Westers ate breakfast with the Astorians, then prepared to take their leave. Thompson had a shipment of trade goods due to arrive on the upper Columbia, and he would have to move smartly to meet them.

The surveyor hired an interpreter to accompany him upstream, then helped David Stuart scout the pathway around the Dalles. Everything went smoothly until they reached the end of the carrying place, where they heard a rumor that one of the chiefs was gathering men to come and steal their guns. Thompson defused the situation with some “sharp words,” then asked for a dozen salmon. He presented most of these to David Stuart, then moved on. According to Alexander Ross, the two leaders parted on amiable and cooperative terms.

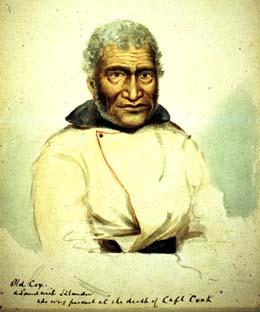

"On Mr. Thompson’s departure, Mr. Stuart gave him one of our Sandwich Islanders, a bold and trustworthy fellow, named Cox, for one of his men, a Canadian, called Boulard. Boulard had the advantage of being long in the Indian country, and had picked up a few words of the language on his way down. Cox, again, was looked upon by Mr. Thompson as a prodigy of wit and humour, so that those respectively acceptable qualities led to the exchange" (Ross, 126).

Thompson later wrote that Michel Boulard, who had been with him for 11 years, had grown tired of the hard work of ascending rivers, whereas Cox was fit and willing. The surveyor still had a long way to travel, and Cox's strength and congeniality would help complete the journey.

After bidding farewell to the Nor'Westers, David Stuart returned to an island near the foot of the Dalles where the rest of his party were "enjoying the repose which we had so much need of" (Ross, 125). Two days later, the Astorians continued upriver in search of a suitable site for a trading post.