In early August 1811, Canadian explorer David Thompson (1770-1857) and a small crew ascend the lower Snake River, visiting a succession of Palus Indian encampments along the way. At a village at the mouth of the Palouse River, Thompson purchases horses, then travels along an Indian trail through present-day Eastern Washington to the Spokane River. In addition to his work as a geographer, Thompson is the fur agent in charge of the Columbia Department for the North West Company of Canada. He has just completed a historic voyage down the Columbia River from Kettle Falls to the Pacific during which he has determined that the Columbia is navigable to the sea and that it will provide a viable fur trade route. He is now returning to Kettle Falls and the upper Columbia, where he will complete the first scientific survey of the entire course of the Columbia.

August 5: A Shortcut

The evening of August 5 found David Thompson at the mouth of the "Shawpatin" (Snake) River, site of the present-day cities of Pasco and Kennewick. Here he stopped for the night near the large fishing village he had visited on his way downriver the previous month.

At some point during his journey, Thompson had learned of a shortcut up the Snake River that would eliminate the difficult upstream paddle around the Big Bend of the Columbia and save him considerable time. This was welcome news, for his canoe was taking on water, he was out of gum to patch the leaks, and there were no trees nearby to tap for more.

August 6: Up the Snake River

"Aug 6th. Tuesday. A fine cloudy Night & Morning" (Belyea, 166). The surveyor purchased a horse from one of the villagers, then presented it as payment to the man who had served as their guide and interpreter from The Dalles. At 7:30 a.m., "we left this friendly Village with hearty wishes for our safe return" (Thompson, Travels iii.296). His seven-man crew -- one Hawaiian, two Iroquois Indians, and four French Canadians -- paddled their cedar canoe up the Snake River, which was running high enough to almost completely cover the willow trees along the shore.

They were now in the homeland of the Palus people, whom Thompson referred to as the "Pilloosees." Spotting a small village on an island, the paddlers pulled ashore, traded for some fresh salmon, and gathered enough driftwood to cook them for lunch -- although small, the surveyor pronounced their taste "very fine."

August 8: A Village of 50 Men

For the next two days, the Nor’Westers made steady progress upstream. As was his habit, Thompson stopped to introduce himself at each scattered fishing camp and small village, counting the number of men who gathered to smoke with him. On his map of the area, he noted "Several small villages of 15 to 35 men" along the lower Snake (Thompson, Map, Sheet 7). On August 8, he observed the Blue Mountains to the southeast and soon noted that he would be turning sharply to the southeast if he continued to ascend the river.

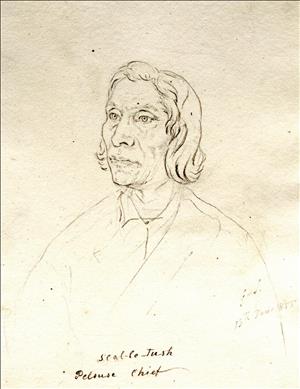

Approaching the mouth of a "small brook" (the Palouse River) on the north shore, the surveyor realized he had reached the shortcut leading north to the Spokane River. Upon beaching their canoe, the Nor’Westers were greeted by 50 Palus men and their families, who "danced till they were tired, and sung and made speeches till they were hoarse" (Thompson, Travels, iii. 296). The site of this encampment, later known as Palus Village, was flooded by the reservoir of Ice Harbor Dam in the 1960s.

After smoking with the men, Thompson explained that he was on his way north and needed to purchase some horses:

"I could proceed no farther in my canoe; and my Men would require horses to carry our things on our intended journey, for which I would pay them on my return from the Mountains; to all that I said they listened, at times saying Oy Oy we hear you; they retired, and shortly after made me a present of eight Horses and a War Garment of thick Moose leather" (Thompson, Travels, iii.296).

August 9: The Nature of a Present

"Aug 9th Friday. A fine day -- Wind a gale southward" (Belyea, 167). Thompson spent the morning making observations with his sextant while his men cached their leaky canoe so that it could be repaired and used at a later date. When it was time to collect the horses for their overland journey, the elderly men of the tribe came and smoked with the surveyor, who offered to pay for the pack animals. But the Palus men retorted that "the Chiefs below us, are good people, but expect to be paid for every thing; we know the nature of a Present, and that it is not to be paid for" (Thompson, Travels, ii.257). Although he appreciated the gesture, Thompson knew that the Palus could ill afford to give away so many animals, and insisted on presenting an I.O.U. to each man who volunteered a horse, worth 10 beaver skins in goods at any North West Company post. When the surveyor explained the nature of the credit slips to the Palus, "they were much pleased, though they could not comprehend how a bit of paper could contain the price of a Horse" (Thompson, Travels, Travels iii.297).

It was 5 p.m. before the horses were loaded and ready to set off. The trail, labeled the "Shawpatin and Pilloosees Road" on Thompson's later maps, followed the lower Palouse River, then continued northeast through present-day Whitman County. The Nor'Westers were traversing the Cheney-Palouse Scablands, a swath of Eastern Washington that was scoured by a series of cataclysmic floods during the late Pleistocene. Patches of exposed basalt cut the horses' feet, and Thompson complained that the soil was "a sandy fine impalpable Powder which suffocated us with Dust" (Nisbet, MME, 121). Taking advantage of the long summer evening, their guide led them across the parched landscape until 11:30 that night, when their trail rejoined the river.

Thompson noted that although desolate, there were certain advantages to this arid country:

"Nothing is heard but the hissing of the Snakes, nothing seen but a chance Eagle like a speck in the sky, swiftly winging his way to a better country: but these countries are free from the most intolerable of all plagues, the Musketoes, Sand and Horse Flies" (Thompson, Travels, iii.297).

August 10 - 11: Somewhat Less Rude

According to Thompson’s later maps, his guide left the Palouse River and traveled north through a landscape that was "somewhat less rude" (Belyea, 167). The grass was thicker, a few trees and shrubs appeared along the watercourses, and the furmen sampled chokecherries and three kinds of currants.

On the evening of August 11, they made camp at a pond and one of the men shot a duck. But Thompson's seven-man crew needed more than one duck for dinner. The food they had brought with them was almost gone, and they had had nothing eat all day. Back at the mouth of the Snake River, Thompson had dispatched a messenger to Jaco Finlay, the clerk in charge of Spokane House, with instructions to bring horses and provisions and meet them along the trail. But Jaco and the fresh supplies had not yet arrived, so Thompson decided to kill one of their mares for food.

August 12 - 13: Much Mended

As the trail wound north into present-day Spokane County, Thompson found the country “much mended” (Nisbet, MME, 121). They heard birds singing in willows, saw deer sign, and grazed their horses on bunchgrass that had help up tolerably well, “tho parched up for want of Rain, which rarely or never falls during the Summer months” (Nisbet, MME, 121).

The party passed through the Four Lakes area near modern Cheney, crossed a “large Plain without Water, to the Woods of a Brook," which they followed until it “sank in the Ground” (Nisbet, MME, 121). Here they encountered a Spokane man who guided them to a campsite on a small rill and shared his supply of dried salmon.

The next morning, August 13, an hour’s travel brought them to a ford across the Spokane River, then on to Spokane House, where they found all safe. Jaco Finlay came in that evening with the horses and supplies, having missed Thompson on the trail.