On June 26, 1890, residents of Snohomish, the small settlement on the Snohomish River that is then the county seat of Snohomish County, vote 360 to 21 in favor of incorporating as a city of the third class. The election brings an abrupt end to a fractious volley of words between Snohomish's two weekly newspapers over the class of incorporation and the role of the city's founder, E. C. Ferguson (1833-1911). Contemporaneous historian William Whitfield (1846-1940), describing the 1890 incorporation proceedings from the vantage point of some 30 years later, will recount: "Then for the first time in its history Snohomish enjoyed all the thrills of city politics" (Whitfield).

The Eye vs. The Weekly Sun

Snohomish had already incorporated (after some earlier failed attempts) in 1888 as a city of the fourth class under the law of Washington Territory. But Washington gained statehood the next year and the Washington State Supreme Court threw out the 1888 incorporation under territorial law. When it came time to incorporate under state law, residents were divided over whether to reincorporate as a town of the fourth class with the same relatively small boundaries as the 1888 territorial incorporation, as favored by town founder Ferguson, or to incorporate with expanded boundaries as a city of the third class. Each faction found a voice in one of the weekly newspapers then published in town. The Weekly Sun (which published between 1889 and 1892) saw things Ferguson's way, whereas The Eye (published from 1883 to 1894) took the opposite viewpoint.

"To be or not to be incorporated? That is the question. Are we, or are we not incorporated? That is the other question" (Weekly Sun). So began the Sun's reaction, published on Friday April 25, 1890, to the defeat of a proposition to reincorporate as a town of fourth class, which had recently failed by a vote of 170 to 53.

On the following day, The Eye published its report on the vote, explaining that the majority of voters "desired to incorporate as a city of the third class and not be hampered with the small area of territory and limited powers conferred upon a town of the fourth class, as proposed by the tax-dodging 'leader' who desires to enjoy all the benefits of a municipal organization, and the improvements made thereunder, without contributing his just share of attendant expenses" (The Eye, April 26, 1890).

The unnamed "tax-dodging leader" was most likely E. C. Ferguson. Thus, in the rush of weekly words generated by Snohomish's nascent fourth estate, a new moniker for Emory Canda Ferguson may be added to "postmaster, mayor, realtor, salon keeper, store proprietor, legislator, even justice of the peace" ("Ferguson, Emory").

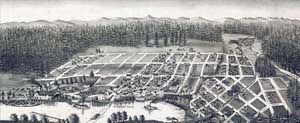

And husband. Ferguson married Lucetta Morgan (1849-1907) in 1868. Together, three years later, they platted a claim on the north bank of the Snohomish River and named it "Snohomish City" after the river. Twenty years later Ferguson was still the largest landowner in town. His property included approximately 10 blocks of undeveloped lots west of Avenue D, clearly indicated in a bird's eye view of the town published in 1890 by the Sun Publishing Company. Absent other evidence, we are left to imagine that the western boundary of Snohomish's 1888 incorporation was Avenue D (as it is for the nationally registered Historic District approved in 1973).

Boom Times

Business leaders, led by Ferguson, who was serving in the territorial legislature at the time, attempted to incorporate Snohomish as early as 1883. Yet an election called for on January 14, 1884, was not held due to a lack of agreement on the boundaries, and it was not until December of the following year that a motion to incorporate was defeated, 18 to 22. Perhaps people were too distracted to vote since 1885 was the beginning of Snohomish's first economic boom according to Whitfield, our historian on the scene.

The Blackman Brothers Company was ready with bundles of kiln-dried red cedar shakes to ship back east ahead of the railroad's 1888 arrival. The brothers' invention of a steam engine to move the harvest on cars running on wooden tracks, a front-page story in the first issue of The Eye in 1883, was soon in wide use around the Pacific Northwest. The architect and builder J. S. White (1845-1920) arrived in town just in time to build the two-story Odd Fellows Hall on 2nd Street, completed in 1885 (and still standing in 2010), the preferred site for municipal meetings. By 1890 he was responsible for the finest brick business block on 1st Street as well as the homes of various local business leaders, including a large abode north of downtown for Ferguson's growing family.

The Snohomish Water Works Company was organized in March 1887, drawing its supply from Blackman Lake north of town at a cost exceeding $12,000. A year later, the water mains were extended two and a half miles, prompting thoughts of finally organizing a fire company. Whitfield proudly includes Snohomish's contribution of $500 toward the $84,000 total raised by communities all around Puget Sound to help Seattle recover from its great fire of 1889. Moreover, Snohomish responded to the demand for brick to rebuild Seattle when a Mr. Pearsall started a brickyard in town. A year later, on June 7, 1890, The Eye enthusiastically promoted John Burns's construction of a three-story brick building on 1st Street as a role model for a future downtown Snohomish built of brick. The handsome structure, designed by J. S. White and built with homemade brick, is still standing in 2010 -- a living monument to the boom of 1890.

A Lawyer's Advice

"A large crowd gathered at the Odd Fellows Hall last Friday evening to listen to an address by Hon. S. H. Piles on the subject of incorporation" (The Eye, May 3, 1890). Samuel Henry Piles (1858-1940), later a United States senator, had begun his law career in 1885 in Snohomish, where he occupied an office over Blackman's general store on 1st Street. Five years later, he returned to town as the city attorney of Seattle. He spoke in favor of incorporation de novo: "[Piles] ridiculed the idea that 'we would first have to reincorporate as a village of the fourth class in order to come in as a third class city'" (The Eye), which was Ferguson's contention, as published in the Weekly Sun.

Piles advised the citizens to petition the county commissioners describing the intended boundaries of incorporation, explaining that the commissioners will have a census taken and if 1,500 or more people are counted, "then we can incorporate as a third class city" (The Eye). "Mr. P. said that we were in a position to become a city, and advised us to do so at once" (The Eye). The meeting ended with the appointment of a committee to draft the incorporation petition to be presented to the county commissioners at their next meeting.

Optimism blanketed the Snohomish River valley like the typical fog of an early spring morning. The boundaries drawn up by the committee members ballooned from the bank of the Snohomish River north to include all of Blackman Lake and west to beyond present-day 83rd Avenue SW. The ambitious proposal even overflowed the banks of the Pilchuck River to the east around 6th Street. Often referred to as the "Father of Snohomish" Ferguson found his children in a rebellious mood in 1890 -- his town was growing up.

Ferguson vs. Blackman

The population within the boundaries drawn by the committee was counted at 2,012 residents, well above the 1,500 required for a city of the third class. The June 7, 1890, issue of The Eye posted the legal "Notice of Election," which included the proposed boundaries. Attention turned to the election, to be held at the same time as the incorporation vote, of the first mayor, councilmen, assessor, treasurer, and health officer, who (if incorporation succeeded) would serve until the new city's first elections could be held later in the year.

The Weekly Sun in its June 13, 1890, issue, wrapped up several column inches with this: "From the description here given of this ideal mayor, who is to preside over the destinies of Snohomish, what name is uppermost in your mind. Speak it out! Nominate him! Elect him" (The Weekly Sun). Again, the name that the paper did not mention, for simple theatrical effect or for some other reason lost over the years, was E. C. Ferguson.

The following day, The Eye continued a familiar theme on its pages: "We honor the old settlers of Snohomish and are ready to bestow honor where honor is due, but many of the older inhabitants are too many years behind the times to be placed at the head of our municipal organization" (The Eye, June 14, 1890). Curiously, there is no mention of a preferred candidate, just the continued negative opinion of the unnamed Ferguson, primarily because of his opposition to incorporation with expanded boundaries.

Consequently, it was likely no surprise when, at the Odd Fellows Hall on Tuesday evening, June 16, 1890, some 150 men nominated Hyrcanus Blackman (1847-1921) instead of Ferguson as candidate for mayor on the People's Ticket. Whitfield writes only that Ferguson's friends left the hall vowing to take their fight to the polls, where Ferguson lost again, with 164 votes to 218 for Blackman.

It was a dramatic upset victory for a man well-respected, but unmentioned in either newspaper until the day of the election. Hyrcanus Blackman, the youngest of the three brothers, was the financial officer of the company's logging operations, one of the largest employers in the valley. He was a successful entrepreneur on his own, opening a general store in 1885 and a first class hotel three years later. Plus, he served in a variety of civic leadership roles, including one session with the territorial legislature as a Democratic representative from a Republican district. This explains the two-word headline in the Weekly Sun's July 4, 1890, issue: "Snohomish Democratic." A lot to read into the line "H. Blackman was the first mayor of Snohomish," which is found in many contemporary synopses of Snohomish's history.

In the June 26, 1890, balloting, the incorporation proposal won by a margin of 339 votes. Elected along with Mayor Blackman were Councilmen D. W. Craddock, W. M. Snyder, J. S. White, Lot Wilber, James Burton, and H. D. Morgan; Treasurer D. L. Lawry; Assessor E. K. Crosby; and Health Officer S. E. Limerick.

A Second (and Third) Election

National elections on November 4, 1890, introduced the Australian ballot system in the state of Washington "doing away entirely with the rowdyism which usually surrounded polling booths under the old law," reported the Weekly Sun in its November 7, 1890, issue. Olympia beat out Ellensburg and North Yakima as the state capital. Road bonds in Snohomish County were passed by 327 votes. And the new City of Snohomish led with the number of votes cast in two wards at 418 to second place Marysville's timid 162.

The newly incorporated city's first municipal elections were held a month later on December 2, 1890, and this time Ferguson was elected mayor. His name topped two tickets, with "Tam" Elwell's on a third, yet only 236 votes were cast for mayor and the balloting was barely mentioned in either newspaper. Perhaps all the voting in one year was too much for the citizens of early Snohomish and the majority opted for a return to the good old days.