On February 5, 1893, residents of South Bend seize the records and seals of Pacific County and transfer the county seat to South Bend, as dictated by voters in the previous November's election. Oysterville residents challenged the vote in court, but have lost. The party from South Bend arrives at Oysterville in boats and by foot from the landing at Nahcotta and enters the courthouse to gather the implements of the county government. County Auditor Phil D. Barney (1864-?) resists, but the rest of the Oysterville-based county officials acquiesce and the county's records and seals are loaded onto steamers and taken to South Bend.

Pacific County Seats

The Pacific County seat had been highly mobile in the county's first decade. When Pacific County formed in 1851, the territorial government located the county seat in Pacific City, a small town on the lower Columbia River southwest of present-day Ilwaco. Soon the land on which the town sat became part of a military reservation and the seat moved to Chinookville, also on the Columbia, in 1852. After two years, residents of Oysterville, on the nearby peninsula now known as the Long Beach Peninsula, petitioned the county commissioners for the transfer of the county seat. Oysterville had grown up around the oyster trade in Willapa Bay and an election in 1854 sanctioned the move.

Nearly 40 years later, in 1892, Pacific County's population center had shifted to the east side of Willapa Bay. The Northern Pacific Railway had completed a spur line connecting South Bend, on the Willapa River just upstream from the river's mouth on Willapa Bay, with the main rail line in Chehalis. The railroad's interest in South Bend in 1889 had created a land boom in the town. The town also had industry. Numerous logging operations brought timber to South Bend for milling and shipment to markets along the Washington Coast and in California.

In 1889, the Ilwaco Railroad and Steam Navigation Company completed a railroad from Ilwaco to Nahcotta, south of Oysterville. The channel that ran along the western edge of Willapa Bay approached the shore at its closest point at Nahcotta, making it a more favorable location for landing steamers that plied the bay with passengers and freight. The railroad then carried the passengers to Ilwaco, where they could continue their travels via Columbia River steamers.

Vilified but Victorious

With Oysterville now off the beaten track, Pacific County residents considered moving their county seat again. In an election in November 1892, Oysterville and another peninsula town, Sealand (now part of Nahcotta), along with South Bend, vied for the county government and the business it would bring. South Bend was vilified in other towns' newspapers because its population advantage over all of the rest of the county's towns would give it an advantage in influencing elections.

In a speech given by Thomas Cooper to "Willapa voters" and reprinted in the South Bend Journal, Cooper defended South Bend for county seat, in opposition to all the allegations against it:

"Gentlemen, South Bend and its citizens need no apologies before the people of Willapa. You have seen our city grow to its present proportions from a sawmill village in the space of three years, and in the face of difficulties which could only be overcome by energy, brains, money and abiding faith in the future. While every other new town in the state of Washington has been so dead that Gabriel's trumpet could not awaken them, South Bend has gone on steadily developing its resources and laying the foundations for its future. It is true there have been hard times which have pinched us all, but this condition is general on the entire Pacific coast, and it is to the credit of South Bend that it is in as good condition as we find it.

"The men who decided for the Northern Pacific railroad to build a line to South Bend costing a million and a half dollars knew what they were doing. They knew that with its first class harbor, and geographical position, and the natural wealth of the tributary country, there was bound to be a city at South Bend, and they have proved their belief by what they have done. And if the proprietors of the Sealand site had shown one-tenth of the enterprise of the so-called boomers and speculators of South Bend, they would receive much more consideration at the hands of the people of the county in this contest" ("For Removal").

Marching to Oysterville

After a heated campaign, voters approved moving the county seat to South Bend with a vote of 984 for South Bend, 376 for Sealand, and 109 against moving the county seat from Oysterville. A suit was promptly filed challenging the vote on the grounds that not all of the voters were legally eligible to vote. The court granted an injunction.

When the court ordered the injunction dissolved and Oysterville still refused to relinquish the county government, community members in South Bend held a meeting to discuss the situation. They nominated a committee to develop a plan for taking the county government by force.

On a Sunday morning, February 5, 1893, 85 men from South Bend boarded the Cruiser and the Edgar bound for Oysterville. Arriving there, they found the bay too shallow for landing. The Edgar unloaded its passengers onto smaller boats for landing while the Cruiser traveled on to Sealand to unload at the dock. The passengers then walked to Oysterville.

The two groups rejoined just outside of Oysterville and sent a small group forward to assess the situation in town. Then, "the coast being found clear the parties quietly marched through the town and took possession of the court house. County Clerk Anthony Bowen threw open wide his office door and directed the removal of the records of his office, which were carried in boxes to the shore and from there transported to the steamer Edgar in the batteaux" ("Removed!").

Other county officials on hand cooperated with the crowd except for County Auditor Phil D. Barney. He refused to receive the court order that dissolved the injunction because it was a Sunday and he was not required to accept service of a court order on Sundays.

Violence Narrowly Averted

After the South Bend crowd attempted to negotiate with Barney to no avail, someone broke into his office and removed all of its contents except the records sealed in the vault, which they left. A county commissioner and the county sheriff, who were on hand, both declined to approve breaking into the vault.

Though the Oystervillians "had watched the removal operations in anything by a pleasant mood and without any noticeable display of cordial friendship for the removal party," there had not been any outright confrontations until they reached the auditor's office ("Removed!"). Auditor Barney picked up a chair leg and menaced a Mr. John Hudson from South Bend. Bystanders counseled restraint and violence was averted. Barney relented the following week and turned the remaining county records over to South Bend.

South Bend, County Seat

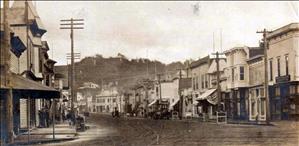

The crowd reboarded the Cruiser and the Edgar and returned to South Bend. They established the county government in the Bristol and Leonard building in downtown South Bend. The next year the Northern Land and Development Company, an arm of the Northern Pacific Railway, donated a lot in "Upper Town," on Quincy Street. A frame building was built by W. B. Murdock of the contracting company Messrs. Murdock & Stanley. In 1911, the current (2011) Pacific County Courthouse replaced the wooden structure.

Gaining the county seat proved to be vital to South Bend's survival. The Panic of 1893 and the ensuing recession brought development to a screeching halt and led to a precipitous decline in population and land values. Robert C. Bailey, a Pacific County historian, identified the county government as one of the key elements of South Bend's stability, along with its family-based population (in contrast to the more transient populations of most lumber towns), its newspapers, which helped develop the town's civic-mindedness, and the railroad terminus.