United States society and its military continued to be segregated during World War II. This segregation included separate camps for blacks or separate housing areas within larger installation. During the war, Washington had three black army camps: Camp Hathaway in Vancouver, Camp George Jordan in Seattle, and South Fort Lewis near Tacoma. There were also separate black encampments within Fort Lawton, McChord Field, and North Fort Lewis. Camps Hathaway and Jordan closed at the end of World War II. South Fort Lewis remained in operation until the Korean War, and was closed in July 1950.

Race and the military before and after World War II

The struggle for equality for blacks was intense during World War II as the United States fought in a global war. During that war blacks were enlisted in restricted numbers and denied opportunities. On July 26, 1948, President Harry S. Truman (1884-1972) issued executive Order 9981, which ended racial segregation in the military. After two years of planning and implementation, in 1950 integration became a reality.

Although integration came only after a long and hard struggle, once the military achieved integration and made it work well, it became a model institution for racial equality. For blacks, World War II became a double-V effort -- V for victory over the enemies of freedom and another V for victory over racial injustice.

Camp Hathaway, Vancouver

Camp Hathaway housed blacks who worked at the Portland Sub-port of Embarkation and black soldiers headed overseas. The camp was established in September 1942 and located on the north side of Vancouver Barracks. More than 100 wood-frame mobilization buildings went up there. This included the common two-story barracks, one-story mess halls, day rooms, and a chapel. The camp's name honored Jeremiah S. Hathaway (1824-1876), who served as a major in the Washington Territorial Volunteers during the 1855-1856 Indian Wars. Hathaway became a prominent Clark County resident, helping to settle the area and serving as a county judge.

Camp Hathaway's black soldiers loaded and unloaded ships at the Portland sub-port. They also drove trucks and did warehouse work. In addition to permanent personnel, black units heading overseas used Camp Hathaway as a staging area, staying at the camp a short time while waiting to be shipped out. While there, soldiers would complete their paperwork, get necessary shots, receive a complete issue of uniforms and equipment, and engage in physical training.

Physical conditioning went on rain or shine and included long daily hikes, training in abandoning ship, and running an obstacle course. Sports teams were formed to occupy off-duty hours and improve conditioning and morale, and the Portland and Vancouver communities collected sports and recreation equipment for those teams. Additional support came from the American Red Cross, which collected and repaired donated furniture for the camp day-rooms. Chaperoned black hostesses came to the camp for dances, and soldiers on liberty visited Portland and the black USO there.

With the end of the war Camp Hathaway was deemed excess, but the adjacent Vancouver Barracks would be retained. In August 1947, the United States War Assets Administration turned over Camp Hathaway, with its 147 acres and 62 temporary buildings, to the Vancouver School District. The school district developed the site into a vocational college, using some of the existing buildings and constructing a new instructional facility, the Applied Arts Building. It cost over $1 million dollars and was ready for the September 1950 start of the Clark Junior College school year. The building had a print shop, machine shop, automotive shop, and rooms for business administration, agriculture courses, and other subjects. The college also acquired surplus buildings in the Ogden Meadows wartime-housing project a few blocks east of the campus. They had offices in former Ogden Meadows administrative buildings. In 1951 Clark College made the former medical clinic there a school for training practical nurses.

Today (2012) Clark College, a private institution, occupies the former camp. The World War II construction has been replaced by new college buildings.

Camp George Jordan, Seattle

A camp for black soldiers opened in August 1942 on the south side of S Spokane Street at 1st Avenue S in Seattle. On November 29, 1943, it was dedicated to black Medal of Honor recipient George Jordan (1847-1904). Jordan was serving in the 9th United States Cavalry when, on August 12, 1881, he displayed exceptional valor. Commanding only 19 soldiers at Carrizo Canyon, New Mexico, he held his position despite attacks from about 200 Indians. He stayed in the army, reaching the rank of first sergeant before retiring to Nebraska. He is buried in the Fort McPherson National Cemetery in Maxwell, Nebraska.

The camp served the Seattle Port of Embarkation and housed 200 soldiers. It was a temporary facility, with 116 "theater of operations" buildings. These were single-story, rough-wood structures with tar-paper siding and roofs. The uninsulated barracks had pot-belly stoves that made the rooms too hot for those nearby and too cold for everyone else. These black soldiers did some of the hardest work with the least glory. They loaded ships, emptied and filled warehouses, and drove trucks and buses. They had few recreational facilities, although the camp did have basketball and baseball teams that played in Seattle leagues and against college teams, such as Bellingham's Western Washington college, in exhibition games. In 1944, the camp's basketball team won the Seattle Service League championship. Liberty time was spent in Seattle, and the black USO was a popular spot.

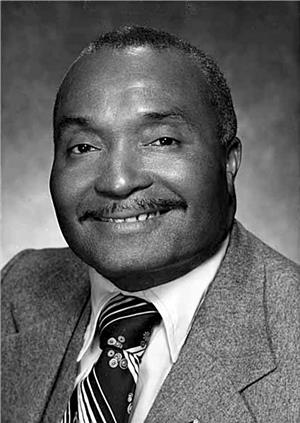

Many Camp Jordan soldiers advanced in the army and contributed to postwar America's success. Sam Smith (1922-1995), born in Louisiana, arrived at the camp in 1942. He became a warrant officer and decided to stay in Seattle after leaving the service. Smith would serve five terms in the Washington State Legislature and was the first black Seattle city councilmember. He fought for social justice his entire life. Sam Smith Park, built on a lid over the Interstate 90 highway, is named in his honor.

Frank Roberts (1919-1989), who served as a white officer at the camp, later described the Jordan troops as the finest he had commanded during his military career. Roberts would become a King County Superior Court judge. He served in the Army Reserve after the war, retiring as a colonel. Another camp soldier,

Alfred Powell (1922-2004), demonstrated his motivation and skill in reaching the rank of major, having served in World War II and the Korean War. Although born in Arkansas, Powell decided to make Seattle his home and attended Seattle University. He later became an official with the Bonneville Power Administration. Powell and other veterans attended postwar Jordan Veterans Association meetings in Seattle.

Camp George Jordan closed in 1946 and was declared surplus in March 1947. Its buildings were removed and the site returned to industrial use.

South Fort Lewis, Fort Lewis

During World War II, Fort Lewis expanded greatly with the addition of three new cantonments. North Fort Lewis was erected across Highway 99 (today Interstate 5) from the existing fort. Another, near Camp Murray, became Northeast Fort Lewis. On the south side near the DuPont Gate (today at Exit 119 of Interstate 5), South Fort Lewis was established. It had 110 wood-frame temporary mobilization buildings constructed in 1941. This cantonment was a separate camp for black soldiers and included typical two-story barracks, mess halls, administrative buildings, recreation center, theater, and service club.

South Fort Lewis had a separate black chapel. It was dedicated on Thanksgiving Day, 1941, in a ceremony that included the famous black athlete, baritone singer, and political activist Paul Robeson (1898-1976). A banquet and reception followed the dedication, with black clergymen from Seattle and Portland as special guests. Paul Robeson also gave afternoon concerts at McChord Field and Fort Lewis. The performances featured his popular songs "Ol' Man River" and "I Got Plenty of Nuttin'." Paul Robeson would become a noted civil rights activist and a controversial figure.

The units at South Fort Lewis included the 55th Ordnance Company; 2nd Battalion, 47th Quartermaster Regiment; 563rd Quartermaster Service Battalion; and transportation units. To aid morale and cohesiveness, an extensive sports program was instituted. The 55th Ordnance black softball team won 50 of its 54 games in 1941. There were also black football teams, including the Staging Area Streaks and the Brown Bombers.

A few blacks were allowed to play on the main Fort Lewis teams. Ford Smith (1919-1983), a right-handed pitcher, won games for the Fort Lewis Warriors baseball team in 1942 before going on to flight school. Following the war, Smith was a leading pitcher on the Negro League's Kansas City Monarchs and later director of the Arizona Civil Rights Commission.

Jonas Gaines (1915-1998), who had played for the National Colored League's Baltimore Elite Giants, was an outstanding left-handed pitcher for the 1943 Fort Lewis Warriors. Lucius Dennis (1924-2004), a former Harlem Globetrotter, played center on the 1944-1945 Warrior basketball team. This limited sports integration in the military preceded and set an example for integration in the civilian sports world.

In 1950 a black unit, the 3rd Battalion, 9th Infantry Regiment, 2nd Infantry Division, was stationed at South Fort Lewis. By June 1950 the Fort Lewis military population, including all the cantonments, housed 20,000 soldiers, with blacks comprising 30 percent of the total. The post was moving to integrate its facilities there, but it was the Korean War and the need for a more effective structure that led to the end of segregation. The 2nd Infantry Division with its black 3rd Battalion, 9th Infantry Regiment, was the first division to ship out for Korea. The 9th Regiment was quickly integrated and had a distinguished war record.

After the shipping out of the 2nd Infantry Division to the Korea War, South Fort Lewis was closed. The underused buildings were demolished in the 1960s.