The Union Bay Natural Area, located along the north shore of Lake Washington adjacent to the University of Washington's East Campus, occupies what was for many years Seattle's largest garbage dump and, slightly to the east, the site of Henry Yesler's (1810-1892) Union Bay lumber mill. The Montlake Dump (also known as the Ravenna Dump, University Dump, and Union Bay Dump and later called the Montlake Landfill) served the city for more than 40 years, and garbage and rubbish of nearly every description was poured into a marshland created by the lowering of Lake Washington in 1916. After the landfill was closed in 1966, there began, haltingly at first, a decades-long (and ongoing) experiment to determine whether, and how, land that has been severely degraded by human activity could be restored to a natural state. Now part of the Center for Urban Horticulture, the Union Bay Natural Area has become a somewhat unique living laboratory. Practicing both active intervention and benign neglect, the center, using mostly volunteers, has since the mid-1980s used the site to study land reclamation, created a protected habitat for a wide variety of plants and animals, and established an urban oasis for walkers, runners, and bird watchers. The one-time landfill today stands as an example of a successful, if yet unfinished, effort to remedy some of the environmental mistakes of the past.

From Lake to Bay and In Between

About 17,000 years ago, the Puget Sound Basin from the Olympic Mountains to the Cascades lay under thousands of feet of ice, the last of at least four periods of glaciation dating back millions of years. About 15,000 years ago, the glaciers began to recede, and by 11,000 years ago the region was glacier-free. Left behind were several ice-carved gouges including, moving east to west, Lake Washington, Lake Union, and Puget Sound.

Lake Washington is nearly 22 miles long, never wider than six miles, and covers approximately 21,500 acres. Before the opening of the Montlake Cut in 1916, its mean height above sea level was approximately 30 feet. However, the lake's water levels could fluctuate by as much as seven feet between wet and dry seasons, causing flooding all along its shoreline.

Directly west of Lake Washington at about its midpoint lies the much smaller Lake Union -- a mere 580 acres in extent -- once separated from its larger neighbor by a narrow isthmus of land. Before that isthmus was bisected by the Montlake Cut in 1916, Lake Union was fed only by small streams, springs, and seasonal runoff from adjacent hills. Its mean height was about 22 feet above sea level, and it drained to Salmon Bay through a small stream in its northwest corner, known variously as The Outlet, Shilshole Creek, or Ross Creek.

Salmon Bay is the last body of water between Lake Washington and Puget Sound. Located in a lowland between Ballard and Magnolia, it was a saltwater tidal inlet attached to Shilshole Bay to the west. Salmon Bay was a popular site for lumber and shingle mills in early-day Seattle, although at extreme low tide it became a large mudflat, cut off completely, if temporarily, from Puget Sound.

The Lake Washington Ship Canal

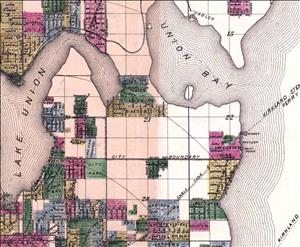

Thomas Mercer (1813-1898), an early settler in Seattle, was quick to see the benefits of connecting the city's two largest lakes to each other and to Puget Sound. Anticipating such an achievement, in 1854 Mercer named both Lake Union (on the south shore of which he lived) and Union Bay, a pouch of Lake Washington that abuts today's University and Montlake neighborhoods.

It would take a little more than 30 years, but the idea of joining the two lakes was simply too good to resist. By 1885, a 16-foot-wide canal had been dug between them by the Lake Washington Improvement Company, used to float logs west to sawmills on Lake Union and controlled by a rudimentary guillotine floodgate. But the Portage Canal, as it was called, was shallow, left the two lakes at different levels, and was of limited value. Before long plans were afoot for a much more ambitious project, one that would allow vessels to move from the farthest reaches of Lake Washington all the way to Puget Sound.

Key to the new plan was bringing Lake Washington, Lake Union, and Salmon Bay to the same mean water level. Construction began in 1911 on what would be called the Lake Washington Ship Canal, with work going on simultaneously on locks and a dam at Salmon Bay; the Fremont Cut joining the bay to Lake Union; and the Montlake Cut that would unite Lake Union's Portage Bay and Lake Washington's Union Bay.

When the lock and dam complex (later named Hiram M. Chittenden Locks) was completed in July 1916, a temporary cofferdam at the Montlake cut was breached. The lowering of Lake Washington and fresh-water flooding of Salmon Bay began, and by October 1916, approximately nine feet of the former had been gradually skimmed off, with the excess water escaping to Lake Union, through the Fremont Cut, over the dam at Salmon Bay, and into Puget Sound.

When the job was done, all three bodies of water stood at the historic level of Lake Union, about 22 feet above sea level, with some seasonal variation controlled solely by the operation of the lock and dam at the west end of Salmon Bay. Vessels could now fulfill Thomas Mercer's dream and travel from the farthest reaches of Lake Washington, through Lake Union, out the locks to Puget Sound, and from there to virtually any place in the world whose shores are brushed by ocean.

Trading Water for Land

The most dramatic physical transformation wrought by the canal's completion was seen on Lake Washington. The lowering of the lake's level by approximately nine feet (sources vary from a little less than nine feet to nearly 11 feet) created a swath of new land around its entire margin. This was viewed as a good thing, especially by property owners around the lake. One benefit of the project was to bring to an end the seasonal flooding that had hampered lakeside agriculture. Increasing the water level in Salmon Bay was less popular. The entire canal project was stoutly opposed by those operating businesses along the bay's original shoreline, but to no avail -- the benefits to canal supporters were too great to be stymied by a handful of mill owners.

With the lowering of Lake Washington, marshland that had been confined to the northern end of Union Bay just north and east of the Montlake Cut was greatly enlarged, reaching to as far south as today's Husky Stadium. The newly exposed land, which held the largest and deepest peat repository in Washington state, was thought to be unbuildable and to have little use and less value.

A Cluster of Dumps

By 1917, two dumps were already in operation just across Lake Washington from Union Bay, one at the south end of today's Washington Park Arboretum and another, called the Miller Street Dump (later known as the Miller Street Landfill), at its north end. Both had opened before completion of the Lake Washington Ship Canal and would be closed by the mid-1930s. The Washington Park site filled a low-lying swale in the Arboretum, and a large portion of that former dump is now home to the marvelous Japanese Garden. After the Miller Street site closed in 1936, it was for several years part of the Arboretum before being taken over by the state during construction of the original SR 520 floating bridge in the 1960s. That area, now called the WSDOT Peninsula, remains state-owned, but may revert to the Arboretum upon completion of the just-started (2012) SR 520 bridge replacement project.

The last dump in the area to open and the last to close was Union Bay's Montlake Dump (which is not actually in Montlake and was also known as the Ravenna Dump, University Dump, and Union Bay Dump). Most of the Union Bay shoreline and beyond to as far north as NE 45th Avenue was owned by the University of Washington. In 1926 it was decided that the marsh could best serve the city as a receptacle for the growing mass of garbage and rubbish that rapid population increases had brought. Before the year was out, commercial haulers started trucking garbage and rubbish to the new Montlake Dump, dropping their first loads in the far northeast corner of the bay near the present intersection of NE 45th Street and Mary Gates Memorial Drive. This started the process of environmental degradation of Union Bay that would, more than a half century later, provide a living laboratory in which to test the ability of humans to atone for past environmental sins.

The Montlake Dump

The Montlake Dump had an unusually long life, and at times was the repository for up to 60 percent of the city's garbage. For 40 years, from 1926 to 1966, stuff of every description was dumped there, almost without limitation and totally without accurate or detailed records. Both organic garbage (primarily food and animal waste) and rubbish (virtually everything else) found its way onto the marshlands of Union Bay. For its first two decades, this was where many City-contracted waste haulers took their loads, dumping great reeking truckloads as often as 100 times each day. After 1949 (although at least one source says as early as 1933) the commercial haulers were joined by ordinary residents, who added to the growing field of refuse one carload at a time, and by private industries, which were permitted to dump God-knows-what with little or no oversight. Along the western edge, nearest Montlake Boulevard, a "burning dump" was started in 1949, with perpetual fires used to reduce some of the dumped material to ash. Neighborhood complaints of smoke and odors brought this to a halt within a few years; all burning ended by 1955.

After burning was stopped, modern sanitary landfill techniques were adopted at the Montlake Dump, which thereafter became officially known as the Montlake Landfill. Starting in 1956, dirt was trucked in each day to cover the latest deposits of trash. The dirt used averaged 9,000 cubic yards a month, and had to cover more than 2,600 monthly truckloads of trash. It helped, but exposed garbage still attracted thousands of seagulls to the site (some estimates said more than 20,000 on a bad day), adding to neighborhood discontent. In 1965, an attempt to rid the dump of seagulls using trained falcons failed.

Another problem that plagued the landfill in the 1950s was peat displacement. In its early days, the dump grew from the shoreline toward the middle, with trucks moving gradually out farther into the center of the swamp to dump their loads. As the accumulated weight of fill increased, the peat deposits, in some places more than 100 feet deep, were squeezed out laterally into the waters of Union Bay, muddying the water and forming an organic soup that threatened to disturb the ecosystem. To correct this, heavy mat walls made of timber and rubbish were built out from the shoreline. These ranged from 15 to 40 feet thick and up to 200 feet in length. The mats were covered with earth of sufficient weight to force them down into the soft underlying peat, effectively blocking its ability to migrate laterally. The end result was a sort of dike, sufficient to support roads for the trucks while creating segregated cells into which garbage and rubbish could be dumped.

In 1962, the Interbay Dump near Smith Cove was closed (albeit temporarily), and the volume of trash arriving at the Montlake Landfill spiked. Also in the early 1960s, the landfill was the recipient of two million cubic yards of free dirt and rubble from the construction of Interstate 5 through Seattle. Much of this was used to build one of two large drainage canals that carried water entering the north end of the landfill from the watersheds of Ravenna and Yesler creeks out to Lake Washington without having to percolate through acres of fetid, and perhaps toxic, refuse.

Through the decades, the University of Washington watched all this activity with proprietary interest. It owned the land and could see that much of what had been unusable marshland was being filled to grade and could, with some adaptation, be put to more productive use. In 1964, the City closed the landfill to the public, hoping to extend its life to accommodate garbage trucked from the city's north end. By early 1965, the university had the City on a very short leash, asserting the right to totally prohibit further dumping with just 30-days' notice. It gave the landfill one more year, but in 1966 almost all dumping there came to an end.

First Steps to Reclamation

The university had begun putting the newly created land in the Montlake Landfill to other use as early as 1946, when the school built housing for married students on the far northeast portion of the tract, within yards of where dumping had started 20 years earlier. Ten years after that, in 1956, the first Montlake parking lot was constructed directly over landfill on the western edge of the dumpsite. One year later, a golf driving range and athletic fields were put in place over the northwest portion of the fill, which remain in place today. But the area posed some unique problems -- in 1957, flammable gases rising through the decaying fill forced the City to put in 15 vent pipes for burning it off as it emerged from the depths, with plans to add 100 more.

Despite the presence of the dump, it is important to note that, certainly as late as 1951, there was still thriving marshland in Union Bay, and its attractions were detailed in a book. In Union Bay: The Life of a City Marsh, by Harry W. Higman and Earl J. Larrison, the authors fill 315 pages with the glories of Union Bay and its wildlife, with only one or two isolated mentions of the massive garbage dump that by that time occupied most of the bay's northern reaches. But one or two passages in the book warn of what the future might bring:

"It is a unique place, this marsh. Man, by building the ship canal, lowered the water of the bay until its margins became a series of exposed flats. Man is therefore responsible for the marsh. If the present trend continues, man, by continual filling, drainage, and building, will some day destroy it. In the past few years the city has nibbled at corners and filled low spots so that the acreage has been slowly but steadily shrinking" (Union Bay: The Life of a City Marsh, 5).

Planning Ahead

Although the Montlake Landfill didn't officially close until 1966, the question of how best to utilize the remainder of the reclaimed land was being examined years earlier. One who tackled the issue was Walter L. Dunn, a professor of engineering at the University of Washington, who wrote of the reclamation efforts as early as 1959. In a later study, from 1966, Dunn described both the promise and the limitations of the old dump site:

"Swamp land that has been reclaimed by filling with refuse placed over peat will never become entirely stable. However, it is quite suitable for automobile parking, open storage, athletic fields, open playfields, and certain types of structures. The value of the reclaimed land is unknown, but this swamp is the only location anywhere near the campus where such large land areas could be obtained at any price" (Dunn, 11).

Dunn also provided a precise breakdown of just what existed on Union Bay's reclaimed areas in 1966: three acres of equipment storage, 13 acres of open playfields, a 12-acre golf driving range, a 15-acre baseball field, 39 acres of general-use athletic fields, 22 acres of automobile parking capable of holding 2,000 vehicles. But what would prove of much greater interest than parking lots and playfields was Dunn's last entry --"Partially filled area (central portion of swamp): 62 acres" (Dunn, 27)

Reclamation efforts got a boost in 1971, when expansion of the university's health sciences complex provided massive amounts of rubble and earth that was spread across the Union Bay site, then graded and seeded with grasses. What had been a major eyesore was soon undulating fields of grass dotted with a few trees and bushes and, together with the shoreside marshlands, it quickly became habitat for a wide variety of flora and fauna. By 1980, a study found more than 200 species of wildlife inhabiting the area, including birds ranging from the common goldfinch (the state's official bird) to much rarer snowy owls.

What to Do?

The closure of the Montlake Landfill in 1966 came at a time of growing environmental awareness. The federal Clean Air Act was passed in 1963, the Water Quality and Motor Vehicle Air Pollution Control acts in 1965, and the first Endangered Species legislation came the year the dumping ended. The passage of the state's Shoreline Management Act in 1971 would protect Union Bay from unregulated development, but for the time being the university was content to let the unused portion of landfill lie fallow and untouched. But not ignored -- as early as 1967, just a year after its closure, the University Arboretum Committee started sketching out plans for a "research arboretum" on the site (1995 Management Plan). Other studies followed, including one in 1972 by the school's Ad Hoc Study Committee for East Campus Development that suggested the area eventually could be used for a greenhouse complex, an ecological demonstration area, and open space.

In January 1974, James S. Bethel (1915-1999), dean of the university's College of Forestry, suggested that the areas of the landfill not already in use be dedicated to "arboretum purposes" (Jones & Jones, 2). By December of that year, the University Advisory Committee on Arboreta had prepared a preliminary concept plan expanding on Bethel's ideas, and it had been approved by the university's architectural commission. In early 1975 the idea received a huge boost when the Northwest Ornamental Horticultural Society provided a $35,000 grant to be used to prepare a master plan for a "Union Bay Teaching and Research Arboretum." Jones & Jones, a Seattle landscape architecture and design firm, was hired to carry out the requisite studies and prepare the plan, which was issued in October 1976.

Jones & Jones described the proposed site as:

"surrounded by parking lots and playing fields, penetrated by housing, parking, and equipment storage yards. The gentle rolling surface supports a grassy cover bordered by cattails and occasional trees. All that remains of the extensive marshlands that once covered the area are the peat island and the small marsh at the eastern edge of the site" (Jones & Jones, 4).

Four broad goals were identified for the proposed arboretum -- teaching, research, public service/display, and stewardship -- and the study highlighted the significance of the site and the project:

"Certain of the unique resources at Union Bay require enhancement, protection, and management; while the opportunity exists to resurrect and convert the site into a facility of international significance — a laboratory on a landfill. To have such an asset owned by a university, for conducting research and monitoring change over the years, is not just feasible to attain; it already exists, a great potential to our ability to re-make a healthy urban environment for man" (Jones & Jones, 1, emphasis in original).

The Center for Urban Horticulture

By 1980, the long-brewing plans for at least part of the reclaimed land were beginning to come to fruition. Ugly and outdated housing along the eastern side of Union Bay, which dated to World War II and was called Union Bay Village, was demolished. Some of the housing was replaced, but adjacent to the landfill on its southeast end, just off NE 41st Street, the university announced tentative plans to build a $5.4 million Center for Urban Horticulture. As explained in The Seattle Times, the proposed center would "become the headquarters for all university arboretum programs and ... focus its activities on the study of plants as functional units to maintain and enhance the urban and suburban environment" and would include "a nursery, display areas, greenhouses, equipment house, teaching and research collections, as well as about 45 acres of the present open grasslands" (Lane, The Seattle Times).

But a slowing economy stymied the university's plans; the legislature cut $2.5 million from its budget, and it was soon determined that if a horticultural center was to be built, it would have to be done largely through private funding. The university would provide the land, however, and by mid-August of 1983 work had begun on the first phase of the proposed center, financed by $1.2 million in donations. Within a month, the university's Board of Regents announced that additional donations received would allow a second phase of construction to begin soon. Contributions came from individuals and from such organizations as the Northwest Ornamental Horticultural Society, the Arboretum Foundation, and the Seattle Garden Club.

Although there never seemed any doubt that the landfill to the west of the horticulture center would be a part of the new program, it received scant attention during the center's early development. The area was to remain largely undisturbed, but much studied, for years.

The Union Bay Natural Area

From the beginning, it was clear that the Montlake Landfill was not a viable site for building construction due to its instability and the continued settling of fill material. Almost without exception, the few structures that had been erected along its edges starting in the 1940s suffered structural damage, and the athletic fields, parking lots, and driving range were in perpetual need of remedial filling and leveling. Almost by default, it seemed, it was recognized that the only productive use for the filled portions of Union Bay was as a natural laboratory.

It took many years, many studies, and a bevy of committees to finally end up with the Union Bay Natural Area as it exists today. Some early efforts to intervene in its natural evolution proved ill advised. An initial attempt in 1986 to rid the land of invasive Himalayan blackberries resulted in the disruption of nesting birds, leading to complaints by local birdwatchers. In response, the university appointed yet another committee, this time to formulate management guidelines for what was then called the Union Bay Research Natural Area. These guidelines were updated in 1995 and 2010 and are valuable in tracing the convoluted history of the site.

The Union Bay Natural Area that has developed over the Montlake Landfill is today composed of "open grasslands, wetlands, woodland, shoreline, and riparian corridor" (Union Bay Natural Area and Shoreline Management Guidelines, 2010). Along with the Washington Park Arboretum and the Center for Urban Horticulture, it is part of the University of Washington's Botanic Gardens and under the overall direction of the university's School of Environmental and Forest Sciences. It is the second largest natural area reserved on Lake Washington, second only to the 320-acre Mercer Slough Nature Park in Bellevue. The 2010 study concisely describes the site's current state and the goals of the UBNA:

"The plan for restoring UBNA is based on working with nature. The land is dynamic and the surface contours have been changing since the landfill days. Ravenna Creek has been reconnected to University Slough, creating a now-living stream. For decades, students have pulled blackberries and planted native plants; woodlands, wetlands, and grasslands currently support diverse plant and animal populations. The overall management guidelines have been, and remain, to plant native plants and increase the site’s natural diversity by creating complex habitat for as many creatures as can be supported" (Union Bay Natural Area and Shoreline Management Guidelines, 2010).

A 1986 study found more than 150 species of flowering plants on the site, most of which were non-native. In 1990, efforts began to control the spread of purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria), which then covered a large portion of the area's wetlands. After tons of it were removed by hand, making barely a dent, in the mid-1990s UBNA's management turned to biological control, releasing Gallerucella beetles that feed on that specific plant to the exclusion of others. The effort was largely successful, leaving just isolated pockets of the invader, kept in check by a permanent population of the useful insects. Another invasive loosestrife, Lysimachia vulgaris, which the beetles eschew, is controlled with herbicides.

Non-native Himalayan blackberries have been another persistent challenge. An aerial survey in 1986 showed that just 5 percent of the natural area was covered with the hardy invader; 10 years later, that had grown to 40 percent. Eradication efforts have been unsuccessful, and management's response has been annual mowing of the UBNA's open grasslands, a practice that is repeated every year in late summer, after most nesting birds have fledged their young.

The greater part of the UBNA is simply observed and largely left alone. The natural area and the university's Union Bay shoreline total nearly 74 acres, and most of what has not been used for parking lots, athletic fields, and other development remains in a natural state. The UBNA takes up about 50 acres, of which 14.5 acres have been fully restored. About half of the restored area, if left untouched, is in danger of reverting to a weed-dominated state and requires continuing attention.

Most visitors today (2012) enter the UBNA from the grounds of the Center for Urban Horticulture at 3501 NE 41st Street. To the east, a trail circles Yesler Swamp, where Henry Yesler in 1888 established a mill and founded the short-lived town of Yesler. The overgrown remains of his Waterway 2, where logs were pulled from the lake for milling, are still visible.

Directly to the west on the other side of the horticultural center lies the larger portion of the natural area, where the Montlake Landfill was located. Two gravel-topped walkways, the Loop and Wahkiakum trails, provide access to both shoreland and the interior of the site. Branching off from the main trails are dozens of grass pathways, loosely maintained but easily traversed, that bring visitors closer to features such as Central Pond, South Pond, and Shoveler's Pond.

Although there are places within the natural area where, visually, the surrounding city does not exist, the audible hum of urban life is always present, but it does not drown out the sounds of nature -- birdsong, the chirruping of frogs, the buzz of insects. There are places, however, where the outside world still rudely intrudes; on the far west side of the natural area, well within its boundaries, sits the university's parking lot E-5, a bleak, graveled rectangle that is slated eventually to be absorbed into the UBNA. Just a few yards west of that, Ravenna Creek, once connected to the city's sewer system but "daylighted" in 2006, now flows freely into Union Slough (sometimes called University Slough), which marks the western boundary of the natural area.

It is obvious to visitors that they are in both an urban natural area and an outdoor laboratory. Certain plots within the site are staked off and signed with explanations of what is being studied. Signs warn walkers where herbicides are in use; grasslands are often dotted with vertical blue plastic pipes to protect young plants, and small, makeshift greenhouses. Adjacent to Yesler Swamp is the Douglas Research Conservatory, where a fenced and locked area is scattered with beehives. It is also visually apparent in places that one is still in the middle of a city -- Husky Stadium looms to the southwest in many views, and the SR 520 floating bridge and its ramps are clearly visible from along the shoreline.

The UBNA offers five distinct habitats, designated "management areas" -- woodland, shrubland, shorebird areas, wetlands, and an "unmanaged wildlife site" ("History @ UBNA"). Since its earliest days it has been a particular paradise for bird watchers, and on many days it seems that every visitor is carrying binoculars. As one "birder" website crows:

"Some 200 species have been seen here over the years, including such delights as American Bittern, Yellow-headed Blackbird, Peregrine Falcon, Merlin, Green Heron, American Pipit, and Rufous and Anna's Hummingbird. The ponds attract migrating shorebirds such as Wilson's Phalarope, Stilt Sandpiper, Semipalmated Sandpiper, Pectoral Sandpiper, Baird's Sandpiper, and Solitary Sandpiper, along with the more common Leasts, Westerns, and dowitchers. Rarities can turn up at any time and include Black-headed Gull, Clay-colored Sparrow, Black Tern, Barn Owl, Sage Thrasher, Chestnut-collared Longspur, and Lapland Longspur. Waterfowl such as Cackling Canada Geese, Wood Duck, Hooded Merganser, and wigeons (both species) are common" ("Seattle — Union Bay Natural Area [Montlake Fill"])

What the Future Holds

The Union Bay Natural Area's most recent Shoreline Management Guidelines were approved by the faculty of the School of Forest Resources in February 2010 and map out future plans for the site. In large part, the guidelines call for the continuation and refinement of activities and methods that have been developed over the previous three or four decades:

- Remove invasive non-native plants and animals.

- Add native plants.

- Maximize habitat diversity and native biodiversity.

- Control human impacts.

- Monitor physical and biological conditions.

- Increase and coordinate teaching and research.

- Enhance personal safety.

- Ensure public accessibility.

- Provide educational interpretation.

The SR 520 bridge replacement project now (2012) underway will result in significant improvement to several elements of the Union Bay Natural Area as one of the project’s mitigation sites. Portions of the shoreline at the site of the new bridge will be damaged by the new construction. Compensation for that loss will be achieved through environmental mitigation projects in the Union Bay Natural Area that will establish new wetlands, improve existing wetlands, and implement other enhancements.

"Mitigation activities at this site will provide shoreline and riparian vegetation to reduce erosion, provide refugia, cover and foraging habitat for diverse species, and maintain and improve connections between the existing wetland and on-site upland habitats and aquatic habitats in Lake Washington. The enhanced native upland grassland and upland forest will serve as buffers for the UBNA site. The proposed mitigation will be developed in consultation with the University of Washington, and is intended to be maintained site as an outdoor laboratory for wetland science" (City of Seattle Analysis and Decision of the Director).

Almost all the work in the Union Bay Natural Area over the years has been performed by students and volunteers, and the mitigation that the State has pledged to make as part of the SR 520 bridge replacement project will be a substantial and welcome addition to those efforts. The Union Bay Natural Area has become a more valuable resource year by year, and the opportunity to mend and monitor different discrete habitats, study them over the long term, and compare the results with adjacent areas that have been left untouched, is perhaps unique. Researchers are gathering a valuable store of knowledge about how urban sites damaged by ill-advised human activity can be returned to a natural state, for the benefit of plants, animals, and people. It is a happy irony that what was once a garbage-filled swamp has now become a perpetual scientific laboratory dedicated to helping urban dwellers live in harmony with the natural environment.