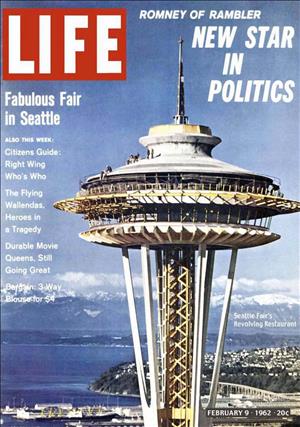

The Space Needle, a modernistic totem of the Seattle World's Fair, was conceived by Eddie Carlson (1911-1990) as a doodle in 1959 and given form by architects John Graham Jr. (1908-1991), Victor Steinbrueck (1911-1985), and John Ridley. When King County declined to fund the project, five private investors, Bagley Wright (1924-2011), Ned Skinner (1920-1988), Norton Clapp (1906-1995), John Graham Jr. (1908-1991), and Howard S. Wright (1927-1996), took over and built the 605-foot tower in less than a year.

The Needle opened shortly before the Century 21 Exposition on March 24, 1962. Owners added a second restaurant-reception room at the 100-foot level in 1982. It was designated as an official historic landmark on April 19, 1999.

The concept for the Space Needle was born in Stuttgart, Germany, when in 1959 Seattle World’s Fair Commission chair Edward E. "Eddie" Carlson dined in a restaurant atop that city’s broadcast tower. Convinced that the World’s Fair needed a similar “restaurant in the sky” as an attraction and symbol, Carlson sketched his idea on postcards to Fair officials, including Ewen Dingwall, Joseph Gandy, and James Douglas. Douglas suggested that Carlson engage the services of architect John Graham Jr., who had recently completed a revolving restaurant in Honolulu.

From Doodle to Reality

Graham was excited by the challenge, and assembled a large team of associates including Art Edwards, Manson Bennett, Erle Duff, Al Miller, Nate Wilkinson, Victor Steinbrueck, and John Ridley. In working to translate Carlson’s doodle into blueprints, they explored a variety of ideas ranging from a single saucer-capped spire to a structure resembling a tethered balloon. Steinbrueck hit on a wasp-waisted tripod for the Space Needle’s legs and Ridley perfected the double-decked “top house” crown.

Fair promoters tried to interest King County in funding the Needle’s construction, but the County declined. Five major Northwest business leaders -- Bagley Wright, Ned Skinner, Norton Clapp, John Graham Jr., and Howard S. Wright -- then formed the Pentagram Corporation to take over the project. Wright Construction was named contractor and Eddie Carlson committed Western Hotels, of which he was then vice president, to run the facility and its main revolving restaurant. The developers purchased the site of an obsolete Fire Department alarm center for $75,000 (the Needle and the 14,400-square-foot plot of land it rises from remain in private ownership).

Erected in Record Time

Construction began on April 17, 1961. Laying the foundation entailed the largest continuous concrete pour yet attempted on the West Coast -- 5,850 tons delivered by 467 trucks over 12 hours. The steel tower itself weighs 3,700 tons and its legs are anchored to the earth by 74 32-foot-long bolts. Eight hundred thirty-two steps lead from the base to the top house, but most people prefer to take one of the three elevators.

Workers topped off the structure on December 8, 1961, and the restaurant hosted a special gala on March 24, 1962, a little less than a month before the Fair opened. Total development and construction cost $4.5 million.

The Space Needle’s scale and novel shape were originally accented with a garish paint scheme, including “Orbital Olive,” “Re-entry Red,” and “Galaxy Gold.” During the Fair, the tower’s base housed an exhibit devoted to “Dentistry Through the Ages of Man,” and the top house peak blazed at night with a giant natural gas torch. The original restaurant was dubbed “The Eye of the Needle.” Its dining floor to this day (1999) completes a full revolution every 58 minutes, powered by a 1.5 h.p. electric motor.

Movies, Stunts, and a Streaker

Initially, this polychrome pylon had its critics, but Seattle -- and the world -- quickly adopted it as the city’s unofficial symbol. Besides gracing countless snapshots and home videos, the Needle has been featured in three major commercial motion pictures: It Happened at the World’s Fair, (1964) with Elvis Presley; The Parallax View, (1974) with Warren Beatty; and Austin Powers, The Spy Who Shagged Me, (1999) with Mike Myers.

Seattle’s village lingam has provided a prop for numerous stunts, including high wire acts and parachute jumps. Students from Tolt High School chewed $150 worth of gum to create a chain of 14,986 wrappers, which they dangled from the Needle on November 20, 1965. Artist-historian Paul Dorpat suspended a 250-foot “Universal Worm” from the tower in October 1971, and artist Alan Lande lit it up as a flying saucer for a science fiction festival in 1978. On June 14, 1974, at the height of the “streaking” craze, a naked man dangled from a small plane as it circled the Space Needle’s restaurant level.

The Needle withstood without damage the Columbus Day windstorm of 1962 and the 1965 earthquake. Except for three suicides who leapt to their deaths from the Needle’s Observation Level, to date (1999) no worker or visitor has been killed or seriously injured in the tower.

An Official Landmark At Last

During the World’s Fair, the Needle attracted 2.3 million visitors and diners, but in the 1970s attendance began to wane. In 1978, the Needle’s owners proposed to add a new restaurant and banquet facility at the tower’s 100-foot level, to serve the throngs expected for Seattle Center’s display of King Tut treasures. Victor Steinbrueck led a spirited public opposition, but the Seattle City Council ultimately approved the addition, which opened four years late on May 19, 1982, as “The Wheedle in the Needle.”

On April 15, 1998, the Seattle Landmarks Preservation Board approved the designation of the Space Needle as a "historic landmark." The designation was made official on April 19, 1999, by the Seattle City Council. It was the first structure approved on the basis of all six designation criteria, ranging from architectural merit to historical and physical prominence. Thus, this symbol of “Century 21” greeted the real twenty-first century as a monument to the past -- and as an artifact of a future that didn’t turn out quite as planned.