On June 25, 1901, former Seattle police chief William L. Meredith (1869-1901) is gunned down by theater owner John Considine (1863-1943) inside the G. O. Guy drugstore in Pioneer Square after Meredith tries unsuccessfully to kill Considine. It's a sensational shooting that's Seattle's lead story in 1901, and people come to Guy's drugstore for years afterward to see holes left in the ceiling by a shotgun blast.

Blood Feud

The two men first met in Seattle in 1889 and became fast friends. In 1894 Considine moved to Spokane and Meredith went with him to work in one of Considine's "box houses." (A box house was a live theater that had gambling and served liquor; many of its waitresses offered more personal services on the side that were frequently provided in small rooms that lined the interior walls of the theater.) They returned to Seattle in 1897. Meredith went to work for the Seattle Police Department as a detective; Considine resumed his operations at the People's Theater downtown. Relations between the two men cooled and by 1900 they were avowed enemies.

Considine knew trouble lay ahead when Meredith was made acting police chief in November 1900. (It became official 60 days later.) He was right: There was a law in Seattle that prohibited women in box houses from serving liquor, and police began enforcing the law -- but only on Considine's block. However, it wasn't long before a "Law and Order League" formed to investigate allegations of vice and corruption against public officials in Seattle. Soon the league submitted a list of charges against Meredith to Seattle's city council. This prompted the council to conduct its own investigation. During the hearings Considine alleged that one of Meredith's cronies had approached him and demanded $500 in protection money, which he'd paid and then seen delivered to Meredith. Meredith retaliated by falsely accusing Considine of impregnating one of his performers, 17-year-old Mamie Jenkins.

On June 21, 1901, the council reported to Mayor Thomas Humes (1847-1904) that Meredith had accepted bribes and allowed illegal gambling in the city, and was unfit to remain as police chief. Humes told Meredith to resign or be fired. Meredith quit the following day. Two days later, on June 24, Considine sent word to Meredith to publicly retract the claim that he'd impregnated Jenkins or he'd sue Meredith for defamation. Meredith acted the next day.

June 25, 1901

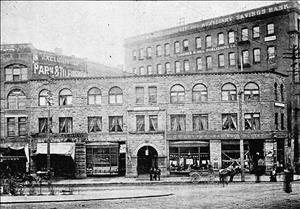

Tuesday, June 25, 1901, dawned cool and clear, but by late afternoon clouds had rolled in and a chilly wind was blowing. The now-former chief armed himself with a cache of weapons: a sawed-off 12-gauge shotgun, a .32 Colt revolver, a .38 bulldog revolver (a gun with a very short barrel), and a dirk (a short knife). He set out looking for Considine. He knew that Considine often caught a streetcar at Occidental Avenue and Yesler Way at the end of the day, and he walked to this intersection. But Considine had a sore throat and wanted to get a gargle for it before heading home on the streetcar. Accompanied by his brother Tom (1857-1933), he stopped by the G. O. Guy drugstore on the southwest corner of 2nd Avenue and Yesler Way. Just as John Considine opened the store's wooden screen door they came upon Patrolman A. H. Mefford, who grinned and stopped to chat. Mefford had his own grudge against Meredith, and he shook hands with the brothers and congratulated John for his role in Meredith's resignation.

It was approximately 5:20 p.m. Meredith, standing a block west on Yesler, saw the brothers approaching the drugstore. He hustled up the street to confront them, carrying his shotgun wrapped in brown butcher paper. The Considines, talking and laughing with Mefford, didn't see him coming. Meredith strode up behind them, aimed his weapon over Tom's shoulder, and fired at John Considine from a range of about 2 feet.

He missed -- barely. The shotgun pellets went through the top of Considine's hat and slammed into the drugstore's ceiling. Unhurt but shocked by the blast, Considine ran into the drugstore. Meredith followed him, stopped just beyond the screen door and fired again. Just as he pulled the trigger the swinging door smacked his arm, skewing his aim. Considine was nicked in the neck by a pellet, but most of them struck G. W. Houston, a train dispatcher, in his left forearm as he sat at the drugstore's fountain counter enjoying a glass of sarsaparilla. (Though he was still dealing with complications from the injury months later, he wasn't seriously injured.)

The Death Struggle

G. O. Guy (1846-1927), owner of the drugstore, was mixing a prescription behind the prescription counter when he heard the first shot. He snuck a peek around the screen that separated the counter from the rest of the store just as Meredith fired his second shot. As Guy described it: "I looked hastily around the screen ... and as I did so, someone from near the entrance fired a second shot, which came unpleasantly close to my head and smashed a bottle on the shelf next to me. I retreated behind the screen again" ("Ex-Chief ...").

Considine ran to the back of the store but was trapped by the prescription counter. Meredith tossed the shotgun -- still wrapped in butcher paper -- to the floor and reached for his .32. At first Considine started to climb over a counter, but saw that would make him a sitting duck. Instead he made a decision that may have saved his life. He was several inches taller and as much as 60 pounds heavier than the small, wiry Meredith. As Meredith drew his gun, Considine turned, ran at him, grabbed him, and began forcing him back toward the front of the store. Meredith managed to get the gun in his hand, but Considine pushed his arm up, keeping it pointed in the air. He screamed for his brother.

Tom Considine and Patrolman Mefford were so shocked by the attack that for several seconds they just stood in the doorway. Then Tom raced up to the Meredith and grabbed him from behind. The Seattle Star described what came next: "A fierce but brief struggle ensued, in which bottles, glassware and expensive bric-a-brac were over-turned from the counter and smashed. Amid the crashing glass, and obscured by the smoke from the discharges of the shot-gun, the death struggle went on ..." ("Meredith's Skull…").

Tom Considine wrenched the revolver from Meredith's hand and slammed it at least five times into his skull, fracturing it in two places; John shouted, "Give it to him, Tom!" ("Meredith's Skull ..."). By this time others were running into the store to break up the fight. Among them were several police officers, including Sheriff Edward Cudihee and Detective A. G. Lane, who had heard the shots from the nearby police station and raced to the scene. Lane and others grabbed Tom Considine and fought him for the gun. Others grabbed John.

A Fiery End

Meredith was dazed; the coroner would later say that his two skull fractures were so serious that they would have knocked most men out at once. But he did not pass out. Head down, he sagged against a showcase, struggled to stay on his feet. Whether or not he still fully knew what was happening or intended to draw another weapon was about to become a topic of fierce debate in Seattle. At that moment John Considine pushed away from the men around him. He'd been warned that Meredith was loudly threatening revenge, and he was armed with a .38 revolver. Now he stepped up to Meredith, drew the gun, and opened fire.

The first shot hit Meredith in the left side and went through his liver. Considine fired a second shot that pierced Meredith's heart and passed through his left lung. Meredith groaned and lunged forward, his coat sparking fire from the heat of the revolver's muzzle. Considine fired again as Meredith fell toward him, striking him in the neck just above the collarbone. Meredith landed face down and died after a few gasps. It had been 90 seconds since he'd first pointed his shotgun at Considine.

Considine turned to Cudihee and handed him his gun. He and his brother were arrested and hustled out of the store. The gunshots had been clearly audible in Pioneer Square, and within seconds hundreds of people stampeded to the scene to see what was happening. Several policemen lined up to keep them out of the store, but the ever-sensational Star provided a written picture for those who missed it: "[Meredith's] face is covered with blood; the mouth is partly open; the face is ghastly" ("Ex-Chief"). Someone called the dead wagon from Butterworth's undertakers and the body was taken away; many in the crowd followed, hoping to sneak a peek at the corpse once it got to the morgue. (They were rebuffed that evening, but the next day they were let in for a look. The P-I estimated that at least 2,500 persons visited the morgue, including "many women and children and hundreds of prominent citizens" ("Few New Facts ...").)

Murder … or Self Defense?

It was a huge story by itself, and it was even bigger because it was the Considine brothers, who were both well-known in Seattle. To put it mildly, they weren't popular with many of the city's more respectable citizens; the day after the shooting, the Star published a florid front-page editorial captioned "Drive Considine Brothers Out of Seattle." But their biggest problem -- especially John's -- was that many who saw the end of the fight said Meredith appeared to have been disarmed and may have been incapacitated before Considine shot him.

Two days after the shooting, both John and Tom Considine were charged with murder in the first degree. John was tried first, in an eagerly awaited and closely followed trial in November that lasted nearly three weeks. He was acquitted, and the State subsequently dropped the charges against Tom. John went on to become successful in vaudeville.