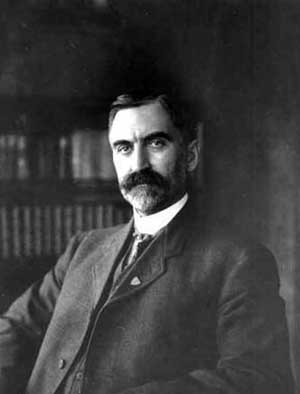

Hiram Martin Chittenden (1858-1917) spent most of his working life with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, where he was involved in the early development of Yellowstone National Park and in navigation, irrigation, and flood-control projects on a number of the nation's inland waterways. In 1906 he became the corps' district engineer in Seattle, where he played a key role in determining the final configuration of the Lake Washington Ship Canal and supervised myriad projects around the state. After retirement from the army in 1910, Chittenden served as the first president of the Port of Seattle Commission, and his efforts to ensure that the Port became a truly public entity did much to shape the future of his adopted city. He and his wife, Nettie Parker Chittenden (1856-1947), had three children, and all three were in attendance in 1956 when the Lake Washington Ship Canal locks at Salmon Bay were named in his honor.

Early Life and Education

Hiram Martin Chittenden was born on October 25, 1858, in Yorkshire Township, New York, about 35 miles southeast of Buffalo, the first child of a farming couple, William Fletcher Chittenden (1835-1923) and Mary Jane Wheeler Chittenden (1836-1924). He was soon joined by two siblings, Clyde (1860-1953) and Ida (1864-1954).

Chittenden was a farm boy and had to shoulder his share of the work, but he excelled in his studies and at age 16 was admitted to the Ten Broeck Free Academy, a training center for future teachers that offered a college-preparation curriculum. While there he formed an ambition to become an attorney and met his future wife, Nettie M. Parker.

In the summer of 1878 Chittenden accepted both a scholarship to Cornell University and an appointment by his congressman to the United States Military Academy at West Point. He studied at Cornell for two terms before transferring to West Point in the late spring of 1880. Academy life did not at first agree with him; his letters home complained of the seeming pettiness of military discipline, the silliness of hazing, even his classmates' profanity. But he soon fit in and once again excelled academically.

Chittenden graduated from West Point on June 15, 1884, ranking first in his class in discipline and third overall. Now a second lieutenant in the Army Corps of Engineers, in September 1884 he began a three-year course of study at Willets Point, the corps' engineering school in what is now the borough of Queens in New York City. On December 30 that year he and Nettie were married at Arcade, her home town. They would go on to raise two sons and a daughter.

While studying engineering at Willets Point, Chittenden also arranged to read law with an attorney in nearby Flushing. In December 1886 he was promoted to first lieutenant, and by March 1887 was admitted to the New York state bar. He never practiced law, but the training would prove useful in a career that often involved reconciling competing interests -- financial, legal, and political -- with the dictates of sound engineering practice.

Embarking on a Career

From July 1887 to September 1888, Chittenden served with the army's Department of the Platte, doing primarily surveying and mapping work. One year later he was assigned to the Missouri River Commission, formed in 1884 to improve navigation and control flooding on the nation's longest river. He spent most of this assignment on the government steamer Josephine damming, dredging, and surveying the upper portions of the Missouri.

The growth of railroads had brought river commerce to a near halt, and Chittenden found the work dispiriting. Improving navigation was cited as the justification for much of what he was doing, but he believed the efforts to be largely pork-barrel. He strongly favored irrigation projects, which would both help with flood control and open up vast, previously arid areas to agriculture. In an 1890 essay in the Magazine of American History, Chittenden wrote, with excessive alliteration:

"But the dwellers of the valley being periodically pacified by these paltry pittances from the public purse, the paramount problem of making the river build up that country and convert these arid and barren wastes into productive farm-lands will go unsolved" ("The Ancient Town of Fort Benson...," 425).

Chittenden's opinions contradicted decades of government policy, and it would not be the last time his beliefs put him in opposition to powerful forces.

Working and Writing

Chittenden, never of robust health, caught typhoid fever in the fall of 1890. He was given a six-month leave, and he and Nettie took a delayed honeymoon trip to Europe. Upon their return he was assigned to the first of two tours of duty at Yellowstone. For the next two years, until the spring of 1893, Chittenden supervised as many as 130 men in building new roads and repairing older ones in America's first national park. He also fought efforts by the Northern Pacific Railway to run tracks through the park and contributed (anonymously) a letter on the subject to Harpers Weekly titled "Legalized Vandalism" (Dodds, 17).

In spring 1893 Chittenden was sent to Louisville, Kentucky, to help with maintenance and operation of the Louisville and Portland Canal, and in late 1894 he was transferred to Columbus, Ohio, for similar duties. The work was unchallenging, and Chittenden, by now a captain, put his spare time to good use, authoring his first major work of history, The Yellowstone National Park: Historical and Descriptive. Chittenden later described the book as "somewhat amateurish and freakish" (Dodds, 20-21), but it was well-reviewed and remained in print for decades.

More river and canal work followed, but in 1898 at the start of the short Spanish American War Chittenden was appointed chief engineer of the Fourth Army Corps, with the rank of lieutenant colonel of the U.S. Volunteers. He saw no action during the conflict and at its end returned to the Regular Army at his previous rank.

Between 1899 and 1906 Chittenden held several posts simultaneously: at Yellowstone Park again, where during five summer seasons he supervised construction of additional tourist roads and other improvements; working once more for the Missouri River Commission and managing navigation and flood-control work on the Osage and Gasconade rivers; serving on a commission studying Yosemite National Park; and consulting on loan to the state of California to address flooding issues on the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers.

This would seem enough work to keep several engineers busy, but somehow Chittenden also found time to write volumes of densely researched history. In 1902 what is recognized as his greatest work, The American Fur Trade of the Far West, was published. The three-volume set can accurately be characterized as magisterial and is still considered authoritative more than a century after its publication. The next year saw the release of his two-volume History of Early Steamboat Navigation on the Missouri River, perhaps the only thing that came from his frustrating work on the Missouri River Commission of which he was justifiably proud. It also received glowing reviews.

Chittenden's final substantial piece of historical scholarship, Life, Letters and Travels of Father Pierre-Jean DeSmet, S.J., 1801-1873, a four-volume opus co-edited with Alfred Talbot Richardson (1864-1952) and published in 1905, was less successful. The two labored mightily, but their work was not much embraced by scholars of the Church or of the West.

Interlude

By the spring of 1905 Chittenden was worn out in body and spirit, even questioning his career choice. In March he wrote of railroading, "It all had a life and business air about it that interested me greatly and I wished that my lot had fallen in similar places" (Dodds, 127). He finally sought medical advice; the doctor declared him "a physical wreck" and suffering from nervous exhaustion. With a self-pity often evidenced in his diary but rarely displayed in public, he wrote of his poor health, "I often ask if, in view of the hard and I judge useful work I have done, I deserve it" (Dodds, 127).

By November 1905 Chittenden could not go on. He was given a leave of absence from the Corps of Engineers, and in December he entered a sanitarium in Wauwatosa, Wisconsin. He remained there until discharged in February 1906 "greatly strengthened mentally and physically" (Dodds, 127). That strength would be soon tested -- he was about to become a key player in a long-running and often contentious debate about building a canal linking Lake Washington to Puget Sound.

Coming to Seattle

Chittenden was appointed to head the Seattle District of the Corps of Engineers in early 1906. His jurisdiction encompassed Washington, Alaska, northern Idaho, and northwestern Montana, but his primary duty was to "be in charge of river and harbor works and fortifications of Puget Sound and tributary waters" (Biographical Register..., 854). It was in these waters that he would forge his lasting legacy

When he and his family arrived in Seattle in April 1906, Chittenden noted in his diary that although it was "a crude and ugly place," there was a "spirit that animates this rising community" and it was "surely a city of destiny" (Dodds, 128). Soon he came to believe that much of that destiny hinged on forging navigable links connecting the city's two primary lakes and the salt water of Puget Sound.

Big Plans, Little Progress

As long ago as July 4, 1854, Seattle pioneer Thomas Mercer (1813-1898) had suggested that what local Indians called "little lake" should thenceforth be "called Union because it would one day connect the larger adjacent lake [Washington] with Puget Sound" (Meany, 140). The name stuck and Mercer's prediction eventually came true: The opening of the Lake Washington Ship Canal was celebrated exactly 63 years later on July 4, 1917.

The long saga of fits, starts, and disputes associated with the canal has been amply documented elsewhere. There were disagreements over what route it should follow, how deep it should be, what sort of locks it should have and how many, where they should be placed, and, inevitably, how it would all be paid for. Various plans were proposed over the years, but by 1906 the only thing resembling a ship canal was a 16-foot-wide cut through the Montlake isthmus with two rickety wooden locks to keep Lake Washington from rushing into Lake Union. The two lakes were tentatively linked, but a passage to Puget Sound was more than a decade away.

The Engineer

Coincidental with Chittenden's move to Seattle, in the spring of 1906 developer James A. Moore (1861-1929) offered to complete the canal at a cost of $500,000. Moore would do the necessary work to link Lake Washington, Lake Union, and Salmon Bay, which was then a tidal inlet extending from Puget Sound inland about half the distance to Lake Union, and would build a timber lock at the head, or eastern end, of Salmon Bay. Moore proposed that three years after completion, ownership would be turned over to the federal government. King County voters approved a $500,000 bond issue to finance the project.

Federal jurisdiction over the nation's navigable waters made congressional approval necessary and Chittenden's involvement inevitable. In early May 1906 he was instructed to review and critique Moore's plan. He found fault with it, which he duly reported on May 26, but on June 11 President William Howard Taft (1857-1930) signed a bill accepting Moore's proposal. The very next day, Washington Governor John McGraw (1850-1910) admitted to the Seattle Chamber of Commerce that it was the boosters' hope that Moore's canal, however inadequate, would prove so valuable to commerce that the federal government would be forced to step in and pay for necessary improvements.

Chittenden was disappointed, but his duty now was to prepare a full report on how to accomplish the task. He made suggestions for alterations to Moore's plan, the most controversial having to do with the number, placement, and type of locks. Chittenden proposed that there be both a large and small lock, constructed of masonry and placed side by side at the narrow foot (western end) of Salmon Bay, rather than Moore's single wooden lock at the head of the bay.

Chittenden agreed that the timber locks at Montlake should be removed and the Montlake Cut widened and deepened, which would lower the level of Lake Washington by several feet. That water would flow unimpeded through Lake Union into Salmon Bay. Herein lay the rub -- if the locks were located at the foot rather than the head of Salmon Bay, the water level of the bay would rise and the prosperous shingle mills that lined its shores would be inundated and need to be elevated at great expense. Mill owners, to say the least, were not pleased, nor were they without political influence.

Chittenden was in an uncomfortable position, one in which he could urge but could not command. The Salmon Bay mill owners had endorsed Moore's proposal only after receiving assurances that their interests would not be harmed, and Chittenden's proposal would violate that understanding. Reluctantly, he punted, and acknowledged that the decision should be made by local interests who (at that time) were committed to fund the work.

Chittenden had many more matters under his jurisdiction. In 1906 alone these included the evaluation or implementation of projects to deepen the Willapa River, cut a channel between Cosmopolis and Hoquiam, remove obstructive rocks in Roche Harbor and Bellingham Bay, survey and straighten the Duwamish River, survey the harbor at Olympia, build a dike on the Snohomish River, dredge Whatcom Creek, remove a wrecked ship from Willapa Harbor, and several other assignments. In his report to headquarters that year he also noted that Congress had approved "the construction of the Lake Washington canal by private capital under government supervision" ("Tells of Year's Work").

Arguments over the details of the canal project went on for years. At one point Chittenden switched positions and endorsed putting the locks at the eastern end of Salmon Bay, apparently an effort to just get things off dead center. Moore eventually demanded conditions that were deemed unacceptable, then withdrew his proposal, leaving matters in limbo. The issues were finally resolved in June 1910, when Congress passed a statute that provided up to $2,275,000 to build "a double lock ... to be located at 'The Narrows,' at the entrance to Salmon Bay" (36 Stat. 666). After nearly four years of debate, almost everything Chittenden had recommended in 1906 was adopted, but by this time he had retired from the Corps of Engineers and would have no further formal involvement with the canal, still more than six years from completion.

The Invalid

Chittenden's health had been deteriorating almost since his arrival in Seattle, and the decline was hastened and exacerbated by an unwise decision in 1907 to comply with the dictate of the famously energetic president, Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919), that all non-infantry army officers undertake a 50-mile horseback ride as part of their annual physical. Chittenden could have, and should have, sought exemption. He did not, and after completing the ordeal he suffered a major physical collapse that included partial paralysis in his legs. Before the year was out he managed to complete his annual report on the Lake Washington Ship Canal project, then entered into a long period of disability and inactivity. He finally was hospitalized in December 1907 and his useful work for the corps effectively came to an end.

Trouble of a different sort soon followed. Chittenden valued his reputation for probity, and he was mortified in early 1908 when the U.S. attorney in Seattle filed a civil suit and a criminal complaint against Chittenden and his brother, Clyde, alleging that in 1906 they had defrauded the government of some valuable coal-bearing land in Snohomish County. The allegations were without merit, and Chittenden was held in such high regard that influential people at all levels of government rose to his defense. The criminal case was soon dropped, and on May 15, 1908, Federal District Court Judge Cornelius H. Hanford (1849-1926) dismissed the civil case as well, fully vindicating Chittenden's reputation.

In February 1908 Chittenden had learned that his life insurance, for which he had been paying premiums since graduation from West Point, had become worthless upon the failure of the insurance company, and that his ill health disqualified him for a replacement policy. The insurance was meant to provide some security for his family after his death, which did not seem to be too far in the future. Two weeks after that news, Chittenden was told that the Robert Clarke Company, publisher of his 1895 volume on Yellowstone, had gone into bankruptcy, threatening the small income he still enjoyed from the royalties.

In July 1908 Chittenden was given a four-month leave of absence, followed by an additional six-month leave in January 1909. When that ended in June, still wracked by ill health, he requested retirement. Because there was talk of a promotion to brigadier general, bypassing the rank of colonel and increasing his pension, he was persuaded to take further leave instead. In July 1909 he had unsuccessful back surgery in Chicago that left him essentially paralyzed from the waist down. Helped by the aggressive lobbying of high-ranking politicians and bureaucrats, his promotion came through in February 1910, and Chittenden's retirement after 36 years of service with the Corps of Engineers became final.

Remarkably, what may have been his greatest contribution to the city he now called home lay ahead.

The Port Commissioner

On March 14, 1911, Washington governor Marion Hay (1865-1933) signed the Port District Act. The law authorized local voters to create public port districts, independent government bodies having the power to levy taxes and issue bonds to acquire land and construct harbor improvements and terminal facilities. King County citizens were to vote on September 5, 1911, on a proposal to establish a county-wide public port district and, if approved, to elect the first three port commissioners, each representing a different portion of the county. Chittenden, although in constant pain, still had an active intellect, and was urged by friends to seek the seat for the central district. When the votes were counted, the creation of the port was approved and Chittenden received more than twice as many votes as his nearest opponent. Also elected commissioners were Robert Bridges (1861-1921) and Charles Remsberg. At its first meeting, on September 12, 1911, Chittenden was made the first president of the Port of Seattle Commission.

The Port Commission's primary responsibility was to develop a comprehensive plan for port financing and development that would be presented to voters in an election to be held barely a year later. On January 21, 1912, the commission presented its recommendations in a full-page article in The Seattle Times. It called for piers, grain elevators, cold-storage plants, and moorage for the city's fishing fleet, and it seemed sure to receive public approval.

But almost immediately the Port Commission was faced with a competing plan, spawned on the East Coast in collaboration with the local owners of Harbor Island, the artificial land mass built on fill at the mouth of the Duwamish River on Elliott Bay. Their plan had the aggressive support of the city's two leading newspapers and the Chamber of Commerce and was relentlessly touted as the better alternative.

The Harbor Island plan was suspiciously complex. The owners of the land proposed that the Port of Seattle sell $5 million in bonds to buy 147 acres on the island, and a private company they would form would then build terminal facilities there. The port would lease the land to the company, but with the rent deferred for 30 years, and with the company having an option to extend the lease for an additional 30 years beyond that. Much was left unsaid, and the proposal was vague and tentative in many of its material terms.

The Port commissioners unanimously opposed it, but agreed to let the voters decide, and they took advantage of the ballot amendment to increase the amount sought for their own plans. Voters were given the options of voting for the original commission plan, the Harbor Island plan, neither, or both. They chose both, leaving Chittenden and his fellow commissioners to sort things out

Chittenden knew that the financing behind the Harbor Island plan was shaky, and he and his fellow commissioners demanded changes to the proposal that eventually led its backers to default. With the voters having given the Port more borrowing power than initially contemplated, the commission was set to put into place its comprehensive plan for port development. The first public harbor facilities completed included Fishermen's Terminal on Salmon Bay, two huge piers at Smith Cove, and the original Bell Street Pier. For the time being, Harbor Island remained in private hands, but as Chittenden predicted, it would later become the site of major Port terminals -- publicly and not privately owned. Today Seattle has one of the finest public ports in the world, and much credit is due Hiram Chittenden.

The Man

Almost all of the Port's initial comprehensive plan was completed by the fall of 1915 and Chittenden, his engineering expertise no longer required, resigned from the commission effective October 15 that year. He served on the advisory board to the Department of Civil Engineering at the University of Washington, wrote occasional articles for engineering journals, advocated for world peace, proposed a 30-mile-long tunnel through the Cascade Mountains that was never built, and did what little consulting work, primarily on flood control, that his tenuous physical condition allowed.

Throughout his career Chittenden had demonstrated an enormous capacity for hard work, despite his frequent bouts of illness and disability. He was opinionated and he was punctilious, but he was far more often right than wrong on matters within his professional expertise. He could seem austere and at times self-righteous, but he was a loving and loyal husband and a devoted father, and he could boast of many close friends from all walks of life.

He was also essentially a nineteenth-century man, steeped in the now-discredited tenets of Social Darwinism, particularly a belief in the superiority of "the Anglo-Saxon race" and a view that Native Americans were "a weaker race" and bound to disappear, something that he felt "sentimental humanists" did not understand (Dodds, 98). Nonetheless, he was openly critical of the federal government's brutal treatment of Indians, believing that, though doomed, they should be treated with "simple justice" (Dodds, 99).

Chittenden's more distasteful opinions were widely shared among his peers and throughout the dominant society. The Corps of Engineers at that time seldom acknowledged, much less advanced, the interests of Native Americans while it reshaped the nation's waterways. Much of Chittenden's own work, including on the Lake Washington Ship Canal, evinced little or no regard for the protection or preservation of local Indians' traditional lands and practices. But the benefits brought by his engineering accomplishments can be acknowledged without implying absolution for the unjust consequential harm that often resulted.

Chittenden's health continued to worsen after retirement from the Port. The formal dedication of the Lake Washington Ship Canal on July 4, 1917, was a gala affair, but the man who for four years had patiently pushed and prodded the project to its eventual form was too ill to attend. Seated in a wheelchair, shrouded in blankets, he watched largely in silence from the porch of his home on the western slope of Capitol Hill as a parade of gaily decorated boats passed by. He was heard to whisper, "It is done, it is done" (Dodds, 204). Three months and five days later he was dead, at the age of 58. After a lifetime of hard work, he predeceased both his parents and his two siblings.

On November 19, 1956, a little less than 40 years after Chittenden's death, his contributions to Seattle were at last formally memorialized when the locks at the narrows of Salmon Bay were named in his honor at a ceremony attended by his three children.