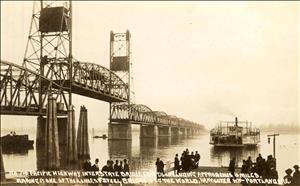

On February 14, 1917, the Interstate Bridge opens across the Columbia River between Portland, Oregon, and Vancouver, Washington. The 3,531-foot-long bridge stretches from Hayden Island in Portland to near the foot of Washington Street in Vancouver. Construction has taken less than two years, and the entire project is completed with money to spare from its $1.75 million budget. The weather cooperates on opening day with fair skies, and after the requisite ceremonies thousands happily vie for the bragging rights of being among the first to cross the bridge.

A Long-Held Dream

As far back as the 1870s, when regular ferry service was just getting underway across the Columbia River between Portland and Vancouver, there were dreams and talk of building a bridge between the two cities. High water during the spring and fall months and occasional ice buildup in the river during winter months could impede travel, and even when the weather wasn't an issue, crossing the river could be treacherous.

As the population grew in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and railroads spread through the Northwest, talk of a bridge grew louder. A railroad bridge across the Columbia opened in 1908 about a mile downriver from where the Interstate Bridge would later be built, but this didn't solve the problem for people wanting to cross the river on foot or horseback, by wagon, or in a recent but increasingly common mode of transportation, by automobile.

In 1912 the commercial clubs of Portland and Vancouver began aggressively advocating for a vehicular bridge. Money was raised to hire a surveyor, and in 1913 both Multnomah County, Oregon, and Clark County, Washington, approved bond measures to finance the project. Once the final bond measure was approved by Multnomah County in November 1913, construction plans moved forward swiftly. By the end of the year the engineering firm of Waddell & Harrington had been selected to design the bridge, and during 1914 plans were drawn up and land was purchased for the project. The engineers presented their final construction plans in January 1915, and within six weeks 24 contractors had submitted bids on the project.

The entire project comprised three bridges and the bridge approaches, which totaled approximately three-and-one-quarter miles in length. Going north from Portland, one would first cross a 300-foot-long bridge over the Columbia Slough. Slightly more than a mile north was the Columbia River, which is split into two channels by Hayden Island. The smaller south channel, known historically as the Oregon Slough, would be crossed by a 1,137-foot-long bridge to the southern side of Hayden Island. The southern end of the 3,500-foot Interstate Bridge would be located on the northern side of the island, and from there it would cross the main channel of the river to Vancouver.

The Interstate Bridge

Ground was broken in a well-attended ceremony on Hayden Island on March 6, 1915. The completion date set for October 31, 1916, wasn't met, but the $1.75 million project (equivalent to $385 million in 2020 dollars) was finished under budget, so much so that there was money for some improvements, most notably an additional approach on the Oregon side. Even with these improvements, there was still $56,000 ($1.2 million in 2020 dollars) left over. Work had been sufficiently completed by the end of 1916 to allow the bridge to be opened for a few hours to pedestrian traffic on December 30 when snow and a cold snap produced ice on the river that stopped the ferry from running.

When completed, the Interstate Bridge was 3,531 feet, five and seven-eighths inches long and had 14 sections. There was a small deck-girder span on the Vancouver end of the bridge, then a series of 13 through-riveted truss spans with curved top chords. Ten of the sections were 265 feet long and three were 275 feet long.

The three 275-foot sections were placed together, and the center one was a vertical-lift span that could be raised between towers on the other two spans, providing a 176-foot-high, 250-foot-wide channel for boats to pass. The lift span was not in the center of the bridge but located closer to the bridge's northern end, where the main channel of the river runs relatively close to the Vancouver shoreline. The bridge's roadway was 38 feet wide, and its concrete floor was five and one-quarter inches thick. There were two lanes for vehicles, with two sets of streetcar tracks running between them. A five-foot-wide sidewalk was on the upstream (east) side of the bridge. Though the bridge was largely complete on opening day, its lighting system still needed to be installed, and a contract for that work was let three weeks later.

An "Ardent Embrace"

On Wednesday, February 14, 1917, the bridge officially opened. Portland's Morning Oregonian crowed the next day, "With brilliant formality … Oregon extended a big, brotherly hand to Washington, and Portland welcomed with open arms her old neighbor, Vancouver. They all fell into each other's ardent embrace, happy over the final realization of an improvement that had been a dream for half a century or more" ("Columbia Span…").

The weather cooperated with mostly fair skies, and while there were a few grumbles about the chill, it wasn't unusually cold for mid-February -- the temperature for most of the day was in the 40s, though a northerly breeze made it feel somewhat colder. By noon, large crowds were gathering on both the Portland and Vancouver ends of the bridge. The Vancouver Daily Columbian estimated a total crowd of 40,000 to 50,000, and the Morning Oregonian confirmed that there were many thousands on each side of the river.

As the official opening time of 12:30 p.m. approached, the dignitaries for the ceremonies caught a streetcar out to the lift span, where a temporary platform had been built. The crowds followed, but were kept 50 feet back from the platform. At 12:30, Multnomah County Commissioner Rufus Holman (1877-1959) rang the bridge bell. His 10-year-old daughter, Eleanor, joined by 7-year-old Mary Helen Kiggins of Vancouver (daughter of Clark County Commissioner John Kiggins), pulled apart a ribbon holding a rope that symbolically marked the border between the two states. The rope dropped, American flags went up, and the crowd cheered. Portland's mayor, H. Russell Albee (1867-1950), shook hands with Mayor Milton Evans of Vancouver, while Oregon's governor James Withycombe (1854-1919) shook hands with Miles Moore (1845-1919), former governor of Washington. (Moore stood in for Governor Ernest Lister [1870-1919], who was expected at the ceremony but did not attend.) The band played "The Star-Spangled Banner," horns honked, bells rang, ships tooted their horns and whistles, and a nearby howitzer boomed.

From Canada to Mexico

Samuel Hill (1857-1931) gave the only speech during the ceremony on the bridge. Hill, a tireless campaigner during the early twentieth century for good roads in the Northwest, proclaimed: "Today the last link is forged in the chain which binds together the whole Pacific Coast from British Columbia to Mexico and now one can pass dry-shod over an uninterrupted highway from Vancouver, B.C., to the Mexican line" ("Columbia Span …"). It would have been more accurate to say that one could pass over an uninterrupted series of roads, not all of them paved. Nevertheless, in 1917 the bridge was a singular achievement, representing a quantum leap in transportation that would be built upon in the coming decades.

At 2 p.m. that day there was another ceremony at Vancouver Park in Vancouver, with plenty of additional speeches. One speaker grudgingly acknowledged that bridge tolls, scheduled to start at midnight, were "temporarily" necessary, but assured the crowd that the "petty tribute" would not last long ("Vancouver Elated…"). The tolls included three-and-a-half cents for streetcar passengers (about 75 cents in 2020) and five cents for one person in an automobile or on a bicycle or horse (the horse cost an extra nickel). Light trucks were charged a 10-cent toll while heavy trucks (more than two tons) were charged 50 cents. Children under age 7 crossed free. The so-called temporary tolls lasted for nearly 12 years before ending in 1929.

In 1940 the streetcar made its last run across the bridge, and its tracks were soon paved over. A second bridge, built immediately to the west of the original, opened in 1958 to accommodate increased traffic. The 1917 bridge was then closed for approximately 18 months for remodeling to more closely match the configuration of the new bridge. When it reopened in 1960, each span became one-way, with the 1917 bridge carrying northbound traffic across the river and the 1958 bridge carrying southbound traffic.