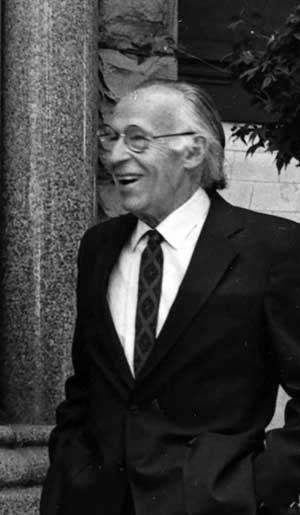

Victor Steinbrueck (1911-1985) was one of Seattle's most outspoken proponents of preservation, conscientious urban planning, and labor. Best known today [1999] for his pen and ink sketchbooks of the city and his work protecting Pike Place Market, his life reflects a number of currents shaping the city's ethos, public policy, and cultural identity. In this orginal essay by Heather MacIntosh, Victor's son Peter Steinbrueck (b. 1957), then a Seattle City Councilmember, recalls his father's life and work.

An Artist at Heart

"He came from a working class background, for one thing," Peter Steinbrueck said of his father. "People think my father was rich. Often fame is associated with wealth. My father broke ranks with the family background ... getting a professional degree. He was well educated, well read and fairly worldly, and always, throughout his life, read and expanded his understanding of a wide range of issues."

When the Great Northern Railroad advanced west in the late nineteenth century, John Steinbrueck followed, bringing his family to the Pacific Northwest from their North Dakota home. John was Victor's father, and one of the many railroad men who migrated from the Midwest. He was an engineer for the railroads, then worked in Seattle's shipyards and participated in the General Strike of 1919, one of the area's and the nation's most influential labor efforts. John then became an auto mechanic, and co-owned a business on Broadway near other car dealerships and repair shops.

John's experience with his business partner, who fronted the money for the business, provided a lesson for future generations of Steinbruecks. John provided the labor for a business with a partner who was only a profiteer, and would prove to be unscrupulous. He made off with the business's funds, leaving John Steinbrueck broke. John taught Victor the value of working and effort through this tough life lesson, and a lifetime of hard work. Conversely, those people who exploited labor and accumulated profits were reviled.

During Victor's education and experiences, his father's life would provide valuable fodder for a well-formed and often articulated morality, based in somewhat socialist beliefs. As his father believed in the value of work and workers, so did Victor. But Victor was an artist at heart, and brought a vibrant and nuanced view of people and society toward his work and family. Over the course of his life, he used many different media to record the environment around him -- mostly Seattle and King County. Peter has a drawing made by his father in 1917. It was his first drawing of Seattle, made during a trip to Pike Place Market from Auburn.

In the 1930s, Victor worked professionally as an artist, with the Works Progress Administration and the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). He generated a series of watercolors illustrating life in the CCC camps. These paintings are now scattered throughout the country -- with at least one in the White House.

Steinbrueck's household was always full of artists -- poets, writers, painters, sculptors. Well known artists of what would become known as the Northwest School of painters -- Morris Graves, Bill Ivey, Mark Tobey among others -- were all family friends. As Peter recalled, "it was the world he loved the most. Architecture gave him a livelihood and provided a way for him to express his art. For years he did wonderful watercolors. There's one right there (hanging on Peter's office wall), 1934 Yesler Terrace before the housing project was built. He won a Northwest Artist Award for that. That was about the time he graduated from Architecture School at UW. He went through several stages. Charcoal renderings, and then the pen and ink when he did books on the city. He did the AIA guide to Seattle, more of a pamphlet. He used pen and ink because it was obviously more portable. Later on he used pastels and made beautiful drawings of still lifes, flower arrangements, and landscapes. He loved the natural landscape around Seattle, and turned us (Victor's four children) all on to parks."

"While he focused on built environment and preservation, and design of the city, his motivation was more about people than about things and objects, about how we live and what we valued," Peter Steinbrueck said of his father. "When you look at saving the Market, it wasn't so much about saving the buildings but about preserving a way of life, especially the presence of local farmers. He valued the relationship between the consumer and producer, which in modern society has been all but lost, enormously.

"Progress wasn't a good thing for him in terms of these traditional relationships, owner-operated mom-and-pop operations and the meaning they had. The culture of the Market, the opportunities availed through that kind of environment, and preserving a place for people with low incomes was very important. The Market was always associated with produce and services catering to these people. Only 30 years ago, the downtown was mostly low-income people. Subsequently more people lived downtown. Only about half as many people live downtown today. He valued the Market's role and wanted to see the it continue to provide its historic function. The social role of the Market was written into regulations protecting it."

According to his son, Victor was an eternal optimist and believed in the good and potential of humankind. He spent his life teaching others by example how to get involved and make a difference in the community. His outspoken beliefs were distinctly anti-capitalist. "Building one's wealth was a selfish and wasted life. This was amoral -- just accumulating money."

Father Figure

Victor Steinbrueck had four children with his wife, Elaine Pearl Worden (b. 1931) -- three boys (Matthew, b. 1953; David, b. 1956; and Peter) and a girl (Lisa, b. 1954). Peter is the youngest. All of Victor's children had limited career choices. Given their father's beliefs, anything smacking of money-making was ruled out. Said Peter: "My brother is a merchant in the market. My sister collects and sells Northwest Indian art and has a gallery, my other brother is a stonemason. All of us work for ourselves, always have. All independent, independently minded, fairly driven but not for wealth."

Victor's principles came through in the way he raised his children. Peter recounts a telling story. When he was a teenager, there was a Safeway in the neighborhood. Safeway workers went on strike, and management posted a sign on the store's windows advertising $6 an hour positions for replacements. "I did a lot of odd jobs, carpentry and such, this sounded appealing, easy good pay, so I got an application form and told dad. He threw a fit. 'You know what that is, you would be a scab! Not on your life are you going to take a job as a scab worker! I knew something about labor history, but not a lot."

Steinbrueck brought to Seattle a kind of preservation mentality that was just starting to grow in other cities around the country in the 1950s and 1960s. His version of historic preservation celebrated the relationships between people and their environment -- both natural and cultural. His drawings and life's work celebrated the working class and the every day, positive interactions between people and spaces.