KJR-AM was the pioneering radio station in the Pacific Northwest, and its history mirrors the rise of the radio industry in general. Its origins trace to a tiny "dot-and-dash" Morse Code transmitter, before founder Vincent I. Kraft (1893-1971) received a formal broadcast license in 1922. But its core story is that of becoming the region's powerhouse broadcaster, one that dominated the marketplace for decades. In the 1950s, Wally Nelskog (1919-2012) reportedly garnered an astounding 50 percent of area listenership with his Wally's Music Makers show. In the 1960s, DJ and Program Manager Pat O'Day (1934-2020) led the way and KJR scored 37 percent at times. KJR earned a nationwide reputation for breaking hits by introducing new records that went on to widespread hit status. KJR nurtured scores of on-air talents -- singers, musicians, announcers, and DJs alike -- who became stars. Although KJR enjoyed an outsized impact on the community for decades, it gradually lost ground to emerging FM stations. Transforming itself, KJR earned a huge and loyal new audience for sports programming.

Arts and Kraft

KJR-AM's century-long history is a complicated and magnificently tangled saga. Detailing every technological advance (it grew from a 5-watt baby to a 50,000-watt giant over the decades); every change of call letters and/or frequencies on the radio dial (a half-dozen times); every occasion that its offices, studios, or transmission facilities moved locations (a good dozen); or the many owners it had (another dozen or so) is beyond the scope of this feature. Instead it focuses mainly on the station's contributions to the community, the most notable stars it nurtured, and its cultural impact.

The earliest years of radio experimentation saw significant activity across America and Europe. In Seattle, Vincent Kraft began serving as the director of Seattle's YMCA School of Radio Telegraphy in 1917, and ran his first "dot-and-dash" Morse Code transmitter under the call letters 7AC. In early 1920, Kraft and O. A. Dodson opened the Northwest Radio Service Company. With a Wonderphone brand microphone and a 5-watt de Forest transmitter, Kraft set up an experimental station above the Groceteria store at 5503 University Way NE in Seattle's University District. That August it broadcast a musical program to most of the 200 local owners of wireless radio receivers -- people who, The Seattle Times noted, "for the first time heard the human voice and music coming in" ("Three Broadcasters Busy").

Over the year broadcasts continued. Kraft moved the operation into the tiny garage next to his Ravenna home (6838 19th Avenue NE). Having installed a 90-foot antenna wire, and hauled a phonograph and piano out there, Kraft applied for a license to operate an experimental station and was awarded the identity of 7XC at 1110 on the radio dial.

"He played phonograph records, coaxed a local piano teacher into performing, and asked a neighbor boy to play the violin. There was no regular schedule. Every so often he would get a call from one of the few people that had a crystal radio set in Seattle, and he would turn on the transmitter and broadcast so they could demonstrate the new 'wireless' to their friends" (Schneider, "Seattle Radio History ...").

Kraft and Dodson proved to be astute businessmen and their downtown shop began offering clients, far and wide, broadcasting gear and expert advice. The ongoing explosion of interest in radio soon caused them to upgrade locations, moving the firm into the sixth floor of the Terminal Sales Building at 1932 1st Avenue in the Belltown neighborhood.

Then in 1921 the rules changed. The Department of Commerce -- which regulated the radio industry prior to formation of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) -- banned experimental stations from broadcasting music and created a new "broadcast service" category. With these changes, the floodgates burst open nationwide. Kraft, among the earliest to apply for a license, was assigned the randomly chosen call letters KJR.

Each new station that applied needed to be inspected by the Commerce Department, and KJR passed its inspection on August 16, 1921. Another station -- KFC, a collaborative project between the Seattle Post-Intelligencer and the Northern Radio and Electric Company -- was inspected on September 12. For unknown reasons, KFC received its license on December 8, while KJR didn't get a license until March 9, 1922. This wrinkle in the history aside, KJR is widely considered to be Seattle's original radio station.

The Big Time

By this point a full-on radio craze was well underway. Kraft relocated his station to a nearby house at 7025 18th Avenue NE, and in 1923 transferred ownership of KJR to the Northwest Radio Service Company. By January 1925 KJR moved again, this time to headquarters in the Terminal Sales Building, where the Northwest Radio Service Company had built a powerful 1,000-watt transmitter from scratch, doubling the station's power. KJR began broadcasting from there on the evening of January 21. The breakthrough brought full-page coverage in that morning's Seattle Post-Intelligencer under the banner headline "New Station Marks Epoch in Seattle Radio."

Broadcasting at 780 kilocycles on the dial, and with a much-larger listening audience, KJR needed more and better content. The Post-Intelligencer stepped in to sponsor live performances by various popular local dance bands, including Vic Meyers's Recording Orchestra. In 1926 KJR built a new transmitter facility at 15th Avenue NE and NE 185th north of Seattle. The upgrade increased its power to 2,500 watts. The station also moved. The offices went to the Liggett Building at 1424 4th Avenue and the studios to the Home Savings and Loan Building at 1520 Westlake Avenue. Later that year Kraft sold KJR to the well-heeled directors of Puget Sound Savings and Loan, Adolph Linden (1889-1969) and Edmund Campbell.

For a spell Linden and Campbell's money "flowed freely, and KJR became among the most popular and best-financed stations in the Northwest. In 1928 KJR boosted its power to 5,000 Watts. It also had a large program staff with announcers, singers, a dance band, and a symphony orchestra" (Schneider, Seattle Radio, 8). All sorts of touring stars passed through KJR's studios, including Marian Anderson, Tito Schipa, Paul Whiteman, and Meredith Wilson. Among KJR's talented crew were singer Sally Jo Walker; staff writer Tom Griffith (later a senior editor at Time magazine); and announcer Ken Niles (who hosted a drama series called Theater of the Mind before making his way to Hollywood, where he served for years as Bing Crosby's on-air foil and also worked in film).

But in August 1929 -- two months before the great stock market crash -- the savings and loan filed for bankruptcy and KJR was suddenly without funding. The power and telephone lines were cut, and staff walked away. Linden and Campbell were soon found guilty of embezzling $2 million from their bank and sentenced to prison.

Depression and World War II Years

During the decade-long Great Depression that followed the economic crash, the entertainment industry suffered greatly. But as free public entertainment, radio remained a popular distraction from the financial gloom as it presented live music by locals, including Owen Sweeten's Band of Bands, Claude Tucker's Orchestra, Paul Tutmarc, and the Bursett Bros. Quartet.

KJR was briefly tangled up in bankruptcy proceedings, but those issues were resolved when Ahira Pierce, owner of Home Savings and Loan, bought it. But he too would soon be found guilty of misappropriation of funds and imprisoned. In late 1930 KJR changed hands again, acquired by the National Broadcasting Company (NBC), which in 1933 leased it to Seattle's Fisher Flouring Mills. The company, which already owned KOMO at 950 kHz, ran both stations as NBC affiliates out of the downtown Skinner Building (1326 5th Avenue).

During the early 1930s listeners enjoyed varied performances by KJR's Mardi Gras Gang, a crew of assorted goofballs, musicians, singers, and more including two calling themselves Gorgonzola Swivelface and Oogie Awful, guitarist Cowboy Joe, tenor Elmore Vincent, music director Henri Damski, band leader Abe Brashen, master of ceremonies Al Shuss, and chief announcer (and "Scottish baritone") Thomas Freebairn Smith. Shuss went on to work as KJR sports director, as later did popular radio singer Bob Nichols. In time, legendary Seattle baseball announcer Leo Lassen broadcast Rainiers games on KJR.

In 1936 the Fisher Broadcasting Company constructed a new transmitter building with a massive 573-foot-tall broadcast tower for KOMO and KJR at 2600 26th Avenue SW near the Duwamish Waterway. In 1941 it bought KJR, which throughout the World War II period played a patriotic role, dispensing vital information to a war-weary public and offering comfort through entertainment. Dick Keplinger hosted KJR's "So Goes the World" daily news program and his stellar work won him an award as "America's top announcer" in 1943. Among KJR's other on-air talents at the time were Seattle organists Eddie Clifford and Tubby Clark; restaurateur and folk singer Ivar Haglund (1905-1985); and singer Martha Wright (1923-2016), who went on to a prominent Broadway and TV career.

In 1944 new FCC regulations prohibited ownership of multiple stations in any one market. So in November 1945, after swapping the two stations' broadcast frequencies -- KOMO got KJR's superior 1000 kHz frequency, and KJR was stuck with KOMO's less desirable 950 kHz -- the Fisher company transferred KJR to Birt F. Fisher (unrelated to Fisher Broadcasting, but an experienced radio man who had owned KTCL, the predecessor to KOMO) in a stock transaction. In 1947 Birt Fisher sold KJR to Marshall Field Enterprises in Chicago.

Wally's Music Makers

Over the next few years, ownership of KJR shifted to a series of short-termers. Then in 1954 former radio-advertising salesman Lester Smith (1919-2012) and his partner John Malloy acquired KJR for $150,000. Soon after, they cut a deal with the Port of Seattle: The Port would buy the station's broadcast tower for $220,000 and provide KJR a 50-year lease to continue using it. In 1955 KJR moved into that KOMO-KJR transmitter building.

That year KJR made a key hiring: Everett's Wally Nelskog, who'd launched his popular Wally's Music Makers on Seattle's KRSC around 1949. Nelskog had also helped pioneer promotion of citywide youth dances in 1950 -- the first act he hired was a combo led by a young Quincy Jones (b. 1933). After Nelskog jumped to KJR in 1955 his program increased the station's listenership dramatically -- he later boasted it drew a 50 percent share of the audience.

In 1957 KJR was sold to actor Danny Kaye (1911-1987) and singer Frank Sinatra (1915-1998), with Les Smith remaining as general manager. Rock 'n' roll was on the rise and Smith responded by hiring fresh on-air talents including Dick Stokke, Jay Ward, Chris Lane, and Lee Perkins. During this period scads of early rock stars including Phil Everly, Clyde McPhatter, and Frankie Lymon stopped by the studios. Another DJ, Ron Bailie, came aboard in 1959 and went on to found the Ron Bailie School of Broadcasting in his garage in 1963. Bailie trained several generations of radio talents before being imprisoned on charges of embezzlement in 1996.

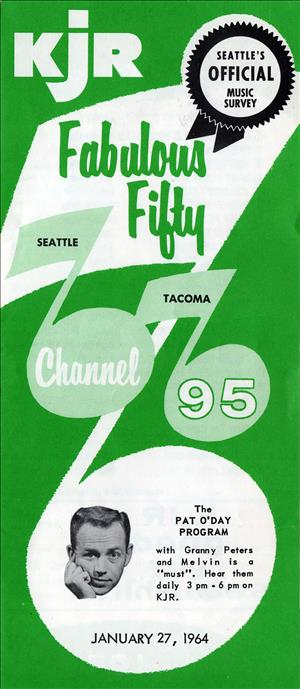

The Fabulous Fifties

In 1959 KJR's Program Director/DJ "Jockey John" Stone made what was the station's most impactful hiring ever: a young DJ from KAYO, Pat O'Day. Born Paul Berg, son of a KMO radio preacher from Bremerton, he was a motor-mouth ham from day one. In 1956 Berg had begun working at KVAS in Astoria, Oregon, where he discovered that he could operate a profitable side hustle as a teen-dance promoter. From there he'd moved to KLOG in Vancouver, Clark County, where one day in 1958 a stranger stepped inside the tiny radio outpost saying he'd been driving along and heard Berg on his car radio.

That man was Nelskog, who by now had built up his own small "cutie" chain of stations: KQTY (Everett), KQDE (Renton), KUDI (Great Falls, Montana), KQDY (Minot, North Dakota), KUDE (Oceanside, California), and KUTI in Yakima. Nelskog instantly offered the kid a job -- but by the time Berg arrived in Yakima, KUTI had been sold and the new owner wanted to switch from Top 40 and rock to an easy listening format. Berg rebelled and was fired. Then, in 1959, an opportunity arose to work at Seattle's KAYO. This was a promising start in a big-city radio market, but the management announced a new Irish marketing theme and each DJ was expected to take on a new Irish-sounding on-air identity. Berg decided to co-opt the name of Seattle's O'Dea High School, and he reemerged as Pat O'Day. He came to prefer the name and eventually adopted it legally.

That year 1959 was a watershed moment for Northwest rock bands, and O'Day played a role in their success. The first band to have national/international hit records was Olympia's Fleetwoods, followed by Seattle's Frantics, then Tacoma's Little Bill and the Bluenotes and the Wailers. In July the Wailers took their "Tall Cool One" single to KAYO's studios and O'Day immediately aired it, helping launch the song as an international hit. O'Day did on-air shifts broadcasting live from a glassed-in "fishbowl" studio in the downtown Seattle Warehouse of Music shop at 419 Pike Street. In October he began airing another new local record, the ballad "Love You So" by Ron Holden (1940-1997), and it rose steadily to the No. 1 chart slot, ultimately becoming a Top-10 international hit.

That November, O'Day instigated an event that must be considered a turning point in Northwest rock history: his first big dance event at the Spanish Castle Ballroom south of Seattle, this one featuring the Wailers. It would be the beginning of the golden years of O'Day's teen dances there by up-and-coming Northwest stars such as Paul Revere and the Raiders, the Kingsmen, Merrilee Rush, and the Sonics.

The Good Guys

Hired in late 1959, O'Day made his KJR on-air debut on New Year's Day 1960. No one knew it yet, but his arrival was another turning point. He brought natural enthusiasm, smarts, comedic wit, a distinct voice, and incredible energy to the task. In January 1961 he was promoted to the important afternoon drive-time jock slot and quickly became the voice of Seattle. Between 1960 and 1962 KJR skyrocketed to a dominant position in the Seattle radio galaxy -- regularly garnering a massive 37 percent share of listeners. O'Day, who would move up to also become program manager and eventually general manager, played a key role in assembling a team of DJs who would be marketed as "the Good Guys."

They included morning drive-time man Lan Roberts, Dick Curtis (1933-2020), Jerry Kaye, and Larry Lujack. All were encouraged to create wacky on-air alter-ego voice characters and to coin goofy catchphrases to entertain listeners. For example, O'Day had the befuddled Granny Peters, the authoritative Mr. KJR, Melvin, and Wonder Mother, while Roberts had his zany Mr. Science, the bumpkin Phil Dirt, the snide gossip The Hollywood Reporter, and the best-forgotten "Clyde, Clyde, the Cow's Outside" shtick.

KJR was now becoming an ingrained pillar of pop culture in the Northwest. Teen R&B bands even began molding their art to catch the station's attention. Especially O'Day's, since he picked hits and booked weekly dances around the area. One band, the Exotics, was induced by O'Day's offers of dance gigs to change its name to the Good Guys.

For all the joy KJR and O'Day delivered, they had their critics. One frequent complaint was the station's failure to embrace harder R&B and Soul music. In one example of how that affected local music, a popular band called the Counts ran their new recording, a bluesy instrumental shuffle, by KJR's Lan Roberts and he told them it was just too R&B for KJR and that they should record it again, this time with a "Jerk" beat. Following that advice -- and even naming the song "Clyde, Clyde, the Cow's Outside" -- got them nowhere.

Seattle's most influential teen R&B combo, the Dave Lewis Trio, recorded one song named "Mr. Clyde" and also a second that was originally released as the "Good Guy's Theme." But then Roberts kicked off another of his silly buzzword phrases: "Little Green Thing." While doing some freeform blathering one day he improvised a contest for listeners, which featured a reward of a "little green thing." What that was no one knew. But it started a citywide craze. That's when Lewis's record company re-released the "Good Guys Theme" record with a new song title: "Little Green Thing." It became a giant regional hit, the biggest of Lewis's career. And before long KJR contest winners began receiving prizes in the mail: tiny bits of green cloth.

In April 1966 Reprise Records released a novelty single called "Wonder Mother," which was credited to "Granny Peters & Clyde." Meanwhile, O'Day continued as a master of self-promotion, along with promoting the station. In 1967 he began many years of work as the race announcer and commentator for KJR's coverage of the annual Seafair Regatta hydroplane races, in which KJR also sponsored its own KJR U-95 hydroplane.

All-American Hits

Another important factor during this period was Les Smith's adoption of a new programming format: Top 40. This was a broadcasting innovation that saw adherent stations committing to playing, in rather regular rotation, the best-selling 40 pop records in their locality. The policy varied from station to station -- KJR still allowed its top jocks to select and slip in a new song or two once in a while. Which is how KJR eventually earned a reputation as one of the leading break-out stations in America, one that debuted new releases and ultimately influenced other stations to pick up those songs, creating retail sales momentum. Just appearing on KJR's new weekly Fabulous Fifty charts, which were printed as brochures and distributed free at record shops, helped boost many a song on its path to hitdom.

This was a blessing for numerous local rock bands. For example, it was O'Day who was on air in 1960 when the Ventures came to the station and asked if he'd consider airing their new recording, "Walk -- Don't Run." O'Day slapped the disc on the turntable, hit the go button, and the record made its radio debut -- one that led to a record deal and the launching of a No. 2 international smash hit. Other local records that KJR helped break as hits included the Wailers' 1961 No. 1 "Louie Louie;" 1963's "Granny's Pad," by the Viceroys; and Merrilee Rush's 1968 Top-10 hit "Angel of the Morning."

After O'Day, who was now winning national broadcasting-excellence awards, was promoted to program director, he continued to recruit talents, including Buzz Barr, Jim Martin, Mike Phillips, "Emperor" Lee Smith, Robert O. "Thorndike Pickledish" Smith, and the self-declared "World Famous" Tom Murphy. And, as ever, the KJR hype machine steamed ahead. For one thing, its jingle -- "KJR, Seattle: Channel 95!" -- was likely the single most-catchy jingle in Pacific Northwest radio history. The station also promoted itself at every opportunity. It gave away thousands of "KJR Go-Go" pin-back lapel buttons and sponsored everything from the World's First Slug Race Festival, to a KJR Water Ski Festival on Lake Washington, to the World's First Buffalo Chip Throwing Contest. The DJs accepted challenges from whichever local high-school basketball team wanted to challenge them, and they drove around town in a custom-made KJR Supercar -- a ridiculously long rocket-styled beast that finally caught fire while participating in the annual Seafair Torchlight Parade. KJR co-sponsored events such as a Halloween Haunted House attraction promoted as a fund-raiser for the Children's Orthopedic Hospital and ran the KJR All-American Race Festival at Pacific Raceways in Kent.

In 1968 O'Day was promoted to general manager, and that February an interesting album was released. Titled KJR 16 All-American Hits, it boasted liner notes credited to "The KJR Dee Jays:" "This album contains some of the Northwest's all time favorites. Over the years we've enjoyed introducing these songs to you." Included were two Seattle-recorded radio hits: "You Turn Me On" by Ian Whitcomb and "The Witch" by the Sonics. Soon KJR Sixteen All-American Hits, Vol. Two was issued. It also included two local hits: the Wailers' 1966 regional winner "It's You Alone" and Merrilee Rush's "Angel of the Morning."

Times They Are A-Changin'

In 1964 Frank Sinatra sold his share of KJR to Danny Kaye and Les Smith. That led to the formation of Kaye-Smith Enterprises in 1968 and the founding of a sister station, Spokane's KJRB. Meanwhile, O'Day was promoted to station manager in 1969. He hired more talents including Charlie Brown, Norm Gregory, Gary Lockwood, and Gary Shannon. But the radio marketplace was changing. Suddenly, freeform countercultural "underground" hippie-oriented FM stations were emerging and starting to undercut the AM pop stations.

KJR was challenged by KOL-FM, and before long by the emergence of heavier or "progressive" or "classic" rock stations including Kaye-Smith's KISW in 1971 and KZOK in 1974. In addition, Seattle saw the debut of its first pro-quality recording facility, Kaye-Smith Studios in downtown Seattle, around 1973.

By 1973 the world had changed so much since the mid-1960s that a wave of nostalgia for those long-gone days was starting to ripple. In September the Increase Records label issued the 12th compilation LP in its Cruisin' series. Each was dedicated to one particular year's hits and a regionally important DJ. Cruisin' 1966 was all about O'Day, and he gamely recreated all sorts of bits that were interspersed between "promotional jingles, sound effects, newscast simulations and even record hop announcements in addition to the original records themselves" (Jacobs). O'Day "lac[ed] his record introductions and public service announcements with corny jokes and puns, cryptic references to specific Seattle neighborhoods (puzzling unless you were living there) and sendups of fellow KJR staffers" (Hopkins).

O'Day stuck it out at KJR into 1974 before moving on, but the station still had other popular on-air talents including Ichabod Caine and Ric Hansen. In 1980 Kaye-Smith sold it to Metromedia for $10 million. In 1982 KJR dropped its Top-40 format, and in 1988 its studios were moved to 190 Queen Anne Avenue N.

Backin' the Kraken

In 1994 a new KJR-FM (93.3 MHz) station was activated with an all-1970s-hits format. That July KJR-AM and KJR-FM were both sold to New Century Media. In 1996 KJR built a new 50,000-watt transmitter along the Duwamish Waterway, but that increased power caused interference at large industrial companies nearby and KJR was forced to move it to Tacoma. In February 1998 one of the New Century Media partners -- Barry Ackerley, owner of the Seattle SuperSonics basketball team -- acquired complete control, while KJR-FM drifted into a classic-hits format.

KJR-AM -- from 1984 through 2006 home of SuperSonics game broadcasts -- was then recast as Seattle's first all-sports talk station. One of its stars, Nanci "The Fabulous Sports Babe" Donnellan, would be recognized as the first woman to have hosted a national sports-talk radio show, resulting in her induction into the Radio Hall of Fame in 2018.

In May 2002, Clear Channel Communications (later iHeartMedia) purchased Ackerley's stations. As of 2022 KJR's studios were at 645 Elliott Avenue W below Queen Anne Hill. Its transmitter is on Vashon Island, and it carries Fox Sports Radio and NBC Sports Radio. Simulcasting since March 2022 on Sports Radio 93.3 KJR-FM, Sports Radio 950 KJR-AM is the home of Seattle's National Hockey League franchise, the Kraken.