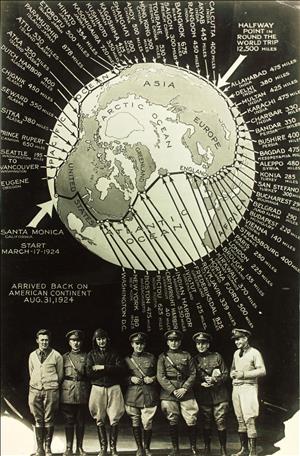

On April 6, 1924, four airplanes lifted off from Seattle's Sand Point Aerodrome in a quest to be the first to fly around the world. The adventure-filled saga was closely followed by many across the globe, especially those who were on the planes' flight path. One aircraft crashed in Alaska and another sank in the Atlantic Ocean, but almost miraculously, there were no serious injuries. The airmen battled bad weather, illness, exhaustion, and mechanical problems, but after a nearly six-month journey, they prevailed. Two of the original planes returned to Seattle on September 28, joined by a replacement plane for the one that sank. The world rejoiced.

Sunburned Knees

In Part 1, the fliers overcome a series of mishaps to reach the midway point of their journey.

After landing in Calcutta on June 26, the world fliers spent the next five days there. It was their main supply and repair base in Southern Asia, and here they switched the planes' pontoons to wheels and did other work on the machines. The men spent some of their evenings at receptions and dinners, and it was at one of these dinners on June 29 that Lowell Smith fell and broke a rib. By then the planes were nearly ready to go, and he insisted that he could continue. There was one task outstanding: There were plans to change the motors in the planes, but this would delay the departure another two days. The fliers decided to change them in Karachi (then still part of India, now in Pakistan).

This decision nearly cost the New Orleans. The planes left Calcutta on July 1, and most of the 1,700-plus mile flight west to Karachi was uneventful, though the aviators grappled with temperatures exceeding 110 degrees. There was some excitement on July 3 when they encountered a sandstorm and were forced to fly just above the ground and follow a railroad track west; it was reminiscent of the snowstorms in Alaska when the pilots dropped below 100 feet to follow the shoreline. The next day they were over uninhabited desert roughly 60 miles east of Karachi when a valve broke in the New Orleans's motor, causing one of its 12 cylinders to fail and briefly spewing parts out of the engine, much to the consternation of Nelson and Harding. Landing in the desert likely would have seriously damaged the plane, but it was able to keep flying to Karachi on slightly reduced power, though it touched down covered with oil.

The men left Karachi on July 7 and enjoyed a mostly-problem free flight to Europe. With pontoons now replaced by wheels, they flew faster and farther between stops. There was one unanticipated problem. Because of the heat, the crews had begun wearing lightweight shorts on their flights, and by the time they reached Iraq, most had sunburned knees. Making excellent time, they reached Baghdad on July 8 and Constantinople (now Istanbul) on the 10th. Continuing northwest, the fliers crossed into Europe and reached Vienna – and cooler weather – on the 13th. The next day they flew to Paris, taking a short detour to pass over the battlefields of the Great War (later known as World War I) in eastern France. Though the conflict had ended nearly six years earlier, the airmen noticed how little many of the battlefields had changed, and at least two of them remarked on it in their daily reports. They were met by an escort of French planes as they approached Paris, where the Americans made a celebratory run over the Arc de Triomphe before landing at the Le Bourget Airdrome.

France and England

It was Bastille Day in France, and a large, enthusiastic throng was on hand to greet them. All the men were exhausted, and Smith was visibly ill. Reporters noticed he was covered in sweat, and when congratulated, he responded only in monosyllables. His broken rib was painful, and he continued to be plagued by dysentery. "Smith is a sick man. Any doctor examining him now would forbid him to fly for weeks, but he refuses to see a doctor," reported the Seattle Post-Intelligencer ("Get Welcome …"). Yet the men dutifully accepted invitations from their hosts to see the city that evening, where one report claimed they were so tired that each of them fell asleep during a vaudeville performance. (Though this particular account may have been exaggerated, there are other stories of individual airmen nodding off during the official functions they were expected to attend at their stops.)

The next day they lunched with U.S. General John Pershing (1860-1948), a hero from the Great War, and flew to England on the 16th. After overnighting in London the men flew to Brough, about 160 miles north of London, where they remained for the next 13 days. They spent much of the time working on their planes, including removing the wheels and reinstalling the pontoons for the upcoming trip across the North Atlantic. They also fielded friendly questions and ribbing from their hosts about their British competitor, Archibald Stuart Charles Stuart-MacLaren (1892-1943), in the race to be the first around the world.

The Americans weren't the only ones trying to circle the globe in 1924 – Argentina, France, Great Britain, and Italy also sent fliers aloft that year – but the most serious competition came from the British. However, this was a gentlemens' race. MacLaren and two crewmen took off from southern England in late March, flying east in a Vickers Vulture amphibious biplane. When the plane crashed on takeoff from Aykab (now Sittwe) Island in present-day Myanmar in late May, the American government arranged to ship the Englishmen a replacement Vulture that the English had in Tokyo. The British effort ended for good on August 4 when heavy fog caused the aircraft to make a forced landing in the Bering Strait off the Soviet Union's Kamchatka Peninsula. Though the passengers were rescued, the plane was damaged beyond repair.

The Boston Is Lost

The American airmen left England on July 30 and flew north to the Orkney Islands off Scotland's north coast. The New Orleans flew on to Iceland on August 2, and the Boston and the Chicago left the Orkneys the next day. Optimism abounded. On August 3 The Seattle Times predicted that the three planes would be back in Seattle on August 19 and in time for Fleet Week. But the paper was wrong. That same day, as the Boston flew between the Orkney and Faroe islands, its oil pressure suddenly dropped to zero. Soon Wade and Ogden could hear the unlubricated engine parts grinding. Knowing that an engine failure was imminent, the men were forced to land in rough seas. The plane was not seriously damaged, and the fliers were rescued by a U.S. cruiser, the Richmond, several hours later. The ship attempted to hoist the craft aboard, but the stormy seas caused the vessel to roll, and the ship's boom dropped on the plane. It damaged the left pontoon, punched holes in the machine's center section and left wing, and broke the propeller.

At first the men tried to repair the plane, but worsening weather made this impossible. They decided to tow it to the Faroes, but the 12-hour ride was too much for the damaged craft. It became waterlogged and sank the following morning, and the crew of the Boston continued to Reykjavik, Iceland, where they rejoined the men of the Chicago and the New Orleans on August 5. There they got some good news. The prototype of the airplane was still available for use as a replacement, and on August 7, the plane – already christened the Boston II – took off from Langley Field (now Langley Air Force Base) in Virginia, for Pictou, Nova Scotia, where Wade and Ogden later rejoined the flight.

Meanwhile, the remaining airmen were stuck in Reykjavik, working on their planes and enjoying the 24-hour summer daylight of the Far North. There was still considerable ice in the harbors at their next destination in Greenland, which delayed the departure and eventually forced the fliers to pick a new landing area. A week passed, then 10 days, and they were still in Iceland. On August 17, they received a surprise when the Italian aviator, Antonio Locatelli (1895-1936), landed in Reykjavik on a stopover in the Italian global quest. Flying in a Dornier Do J Wal flying boat, Locatelli and his three-man crew joined the Chicago and the New Orleans when they took off for Greenland on the morning of August 21, bound for Fredriksdal (now Narsarmijit), 800 miles distant on the country's southern tip.

There was the usual convoy of prestationed supply ships along the route, partly to provide help in case of an emergency, partly to serve as locators to help the fliers confirm their position, and partly as spotters to confirm the planes' passage. The weather was flawless for more than half the flight, but then a thick fog and rain descended. The men were forced to fly just above the water and head due west until they reached Greenland, where they followed the coast to Fredriksdal. Dodging icebergs of all sizes, the planes became separated. Locatelli ran out of gas and was forced down off the coast. He and his crew were rescued three days later by an American supply ship (once again the Richmond), but their plane was heavily damaged and left to sink in the ocean. The Chicago and New Orleans successfully landed in Fredriksdal and flew on to Ivigtut (now Ivittuut) three days later, where they spent a week tuning their planes and changing the motors.

The Boston II Joins the Flight

On August 31, they struck out for the North American continent. Less than halfway into the flight the fuel pump failed on the Chicago, and Smith and Arnold quickly discovered that the backup pump didn't work. Arnold was forced to use an emergency hand pump to feed fuel to the engine for the next four hours until they landed in Ice Tickle (now Black Tickle), Labrador. They quickly made repairs, and on September 3 the Chicago and New Orleans arrived in Pictou, Nova Scotia, where the Boston II and its crew awaited them. The team resumed its journey on September 5, bound for Boston, but heavy fog forced the planes to land offshore near Mere Point in southeastern Maine. Still, they were back in the United States. They arrived in Boston the next day, changed their pontoons for wheels, and continued south along the East Coast. They reached New York on September 8 and Washington, D.C., on September 9, where President Calvin Coolidge (1872-1933) and members of his cabinet met the men at Bolling Field. The president asked Smith to show him the Chicago, and the pilot was happy to oblige.

From there it was a victory cruise across the country, with stops in more than a dozen cities at places as diverse as Chicago and Muskogee, Oklahoma. In the larger cities, the aviators were alarmed by the ever-increasing crowds on hand to greet them. In some places there were so many people that they could not be controlled. After having survived so many scares on the flight, the men worried that the overly enthusiastic masses would damage their planes just when they were almost in sight of their goal. But the crowds behaved, and the victory lap continued across the Midwest and then to California. On September 23 the airmen reached Clover Field in Santa Monica. A rowdy throng estimated at 175,000 was on hand to welcome them, and crowded around the airplanes to such an extent that the fliers were unable to refuel them. After a short delay in San Francisco to replace the engine in the Boston II, they reached Seattle on Sunday, September 28.

Home At Last

It was a warm and sunny day. The anticipated arrival had been closely monitored by the press, and by early afternoon at least 40,000 persons were gathered at Sand Point, while an eager audience on hundreds of boats watched from Lake Washington. Elsewhere in the city people found time to do something outside or kept a hopeful eye out their windows, looking to catch a glimpse of the fliers. Just before 1:30 p.m. an escort of seven planes appeared, followed by the three world cruisers. The crowd erupted in a roar. The planes circled the field twice, took a celebratory lap over Lake Washington, then swooped in to land. The Chicago landed first, quickly followed by the Boston II, and a minute later, the New Orleans.

The public was forbidden from walking onto the landing field until the assembled photographers had finished their work, but the Seattle's pilot, Frederick Martin, was having none of it. He stepped over the ropes separating the crowd from the field. Several guards tried unsuccessfully to stop him but, perhaps recognizing Martin, they stepped back as he strode up to the Chicago. He swung up on a lower wing and shook Smith's hand. "No words were spoken – there was nothing to be said – but the crowd sensed the emotion behind the silent greeting of the former commander and his successor in that brief moment," recounted The Seattle Times ("Major Martin…"). He then climbed on the other two planes and repeated the handshake with the two other pilots.

It had taken the fliers 175 days to circle the globe, 66 which were spent in the air. In the process, they visited 22 countries. The total flying time was 363 hours and 7 minutes, with 76 individual flights made from location to location. They traveled a total distance of 26,345 miles with an average speed of 72 mph. The Seattle Post-Intelligencer said that the planes had consumed 22,260 gallons of gas and 1,026 gallons of oil, and the paper boasted that the pilots had set three new records: first to cross the Pacific Ocean, first to cross the South China Sea, and the first successful around-the-world flight. Of the attempts by a total of five countries to fly around the world in 1924, the American team was the only one that succeeded.

After the photographers had had their fill, the crowd was allowed to swarm the field and greet the fliers. After a few minutes the men were spirited away to the yacht Aquilo just offshore, where they were served a splendid lunch enroute to Madison Park. From there they were driven to Volunteer Park for a welcoming reception. The press commented that Wade, pilot of the Boston and Boston II, stayed in the background during the ceremony, as well as during the other ceremonies given the aviators upon their return. "He seemed to feel he had not fully earned the storm of greeting given the birdmen," explained the Seattle Post-Intelligencer ("Loss of …"). Smith presented each of his fellow travelers to the crowd as the program ended, but the crowd responded by chanting "We want Martin" ("City Gives …"). Fighting back tears, the major gave a brief speech but refused to take the spotlight from the men who had successfully completed the flight. "They did all of the repairing, overhauling and mechanical work on their planes with their own hands. They met and overcame almost insurmountable difficulties," he explained ("City Gives …"). The crowd answered with three cheers.

A Poignant Ending

The fliers were feted at a public luncheon at the Hippodrome the next day, then headed to Sand Point for a 3 p.m. ceremony marking the dedication of a monument in their honor. The granite tower was located immediately to the west of the landing field and described in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer as 15 feet high, three feet wide at its base, and tapering to two feet at its top. A pair of soaring bronze wings atop the memorial symbolized an eagle alighting, and a plaque on its base identified each of the men and the dates of the flight. It was created by Alonzo Victor Lewis (1886-1946), a Seattle painter and sculptor who created several monuments throughout Western Washington in the 1920s and 1930s. The World Flight Monument still stands a century later, now located at the main entrance to Magnuson Park.

The fliers were visibly touched by the sight. "I never thought that a monument ever would be erected to me while I was living," explained Lowell Smith ("Flyers Ordered …"). A crowd of 2,000 listened patiently through a speech or two and watched silently as Frances Cole, sister of Leslie Arnold, slowly removed a large American flag that covered the monument and read the plaque from start to finish. U.S. Senator Wesley Jones (1863-1932) then spoke, and he left the audience with a thought: "We dedicate this shaft to tell the ages of their achievement. Will we add to the glory they have brought by developing all the possibilities they have shown us?" ("Flyers Ordered…").

After the ceremony, the men walked down their field to unpack their planes. It was a poignant moment. They quietly removed their belongings and packed them away in trunks. They silently walked around their planes, clearly reluctant to leave, looking the machines up and down, and touching them here and there. Erik Nelson, pilot of the New Orleans, summed up what most of them were feeling. "This separation hurts more than anything connected with the flight so far. I think many, many thoughts as I look over these wings" ("Flyers Take …").