On June 9, 1948, President Harry S. Truman (1884-1972) begins a whirlwind tour across Washington from Spokane to Puget Sound that will last two days. Although the visit is described as a "non-political" tour, the president nevertheless campaigns for the upcoming fall elections.

Unfinished Business

Harry S. Truman was chosen vice-president in 1944, and had the presidency thrust upon him with the death of Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1945. Years later, Truman stated in his memoirs that he decided to run for the presidency in 1948 because “there was still ‘unfinished business’ confronting the most successful fifteen years of Democratic administration in the history of the country.” He felt that reforms and social programs brought about in the 1930s and 1940s were still vulnerable to attack by political reactionaries, especially as the world readjusted during the postwar period. In effect, Truman was now fighting two wars, the first from Communists abroad, and the second from Republicans at home.

The Congress was the first under Republican control in 16 years. Their intent, in the eyes of Democrats, was to dismantle the New Deal, lower taxes, and limit the power of labor. Truman butted heads with them over all these issues, especially in their attempts to regulate and restrict organized labor. Before leaving on his West Coast trip, Truman referred to them as “the worst Congress we have had since the first one met."

Truman’s 1948 West Coast tour by train was a precursor to the massive whistle-stop campaign he would undertake in the fall. He wanted to get out, meet the people, and let them know first-hand who he was and what he stood for. His train arrived in Spokane on the morning of June 9, 1948. Accompanying him were his wife Bess, his daughter Margaret, and a throng of reporters and staff.

At 9:20 a.m., President Truman’s first talk was at the Spokane Club, where he was introduced by Governor Mon Wallgren and Senator Warren Magnuson. He began his short speech with comments about recent flooding in the Columbia Valley, where he was headed next. Then he told of the problems he was having with Congress. He told the crowd that in the last election, many believed the lies that he felt were published about him. “And two thirds of you didn’t go out and vote. Look what the other third gave you! You deserve it.” He warned the audience that if they didn’t vote again, they would get even more of “just what you deserve."

Before leaving, Truman had a harsh exchange with Ray Felknor, a reporter from the Spokane Spokesman-Review, who asked him how it felt to be in a Republican stronghold. Noticing which newspaper he worked for, the president reiterated his comment that the newspapers were responsible for the last election, and that, “The Chicago Tribune and this paper are the worst in the United States."

The Cross-Statesman

The president then made an unscheduled appearance at the national convention of Communication Workers. He assured them that he was fighting for their best interests, but that it was a hard battle. Truman had vetoed the Taft-Hartley Act (which banned closed shops and restricted other labor activities) the previous year, but Congress had overruled his veto.

Next, the president traveled by car caravan to Grand Coulee Dam. His train left for Ephrata, where he met up with it later. One person who missed the train was the president’s chef, who had run out of butter and detrained to find some in Spokane. When he returned, the train had left, and he had to take a cab 90 miles until he caught up with it.

Truman’s caravan slowed through each town they passed so that waiting crowds could get a glimpse of the President. At Coulee Dam, the largest runoff of water in the short history of the project was tumbling over the top, making for good press photos. Truman enjoyed a quick tour of the facilities, and returned back to his train in Ephrata. He gave a quick talk from the train’s rear platform, and spoke of the power of the Columbia River. He noted that he would talk of flood control and electric power in a major speech he would be giving in Seattle the next day. From there, he left for a quick stop in Wenatchee, and viewed flood damage along the way.

Arrival at Puget Sound

The train left Wenatchee at 5:00 p.m., 90 minutes behind schedule. The trip over Stevens pass was the first chance that Truman had to chat with Senator Magnuson and with Governor Wallgren, who was facing a close race in the upcoming state elections. The train arrived in Everett at 8:45. Smiling at the crowd of 5,000, Truman said he was not fooled one bit. “This crowd turned out for the hometown boy who is governor of Washington.” He went on to say that he came to the Northwest at the urging of Governor Wallgren to see what could be done about work on the Columbia. He speech was short, and the train left for Olympia at 9:10.

Although the train arrived in the state capitol at 2:10 a.m., there were 200 people waiting at the station. The tired president greeted them and left for the governor’s mansion, where he and his family spent the night.

What Did That Man Say?

Truman woke up early for a pre-breakfast stroll. Accompanied by one secret service agent, the president walked through the gardens at the governor’s mansions and the Capitol grounds. Police kept onlookers a block away. After breakfast with the governor, the party left for Bremerton by automobile for an outdoor talk in front of the Elk’s club. They arrived just after 11:00 a.m., and Truman began speaking at 11:40. He told of his cross-state trip the day before, and the beautiful sights he saw. He talked about the Columbia River, and its awesome power.

And then he lit into the 80th Congress. "You know, this Congress is interested in the welfare of the better classes. They are not interested in the welfare of the common everyday man. They said if we lifted price controls, and things of that sort, business would take care of prices. Well, business has taken care of prices, for the welfare and the benefit of the fellows at the top. The poor man is having to pay out all his money for rent and for clothing and for food at prices that are certainly outrageous."

At this point, a voice boomed from the audience. What was said is still under debate. The newspapers stated that a man yelled, “Lay it on, Harry!” Presidential notes claim that the voice said, “Pour it on, Harry!” But there are those in Bremerton who insist that what was said was “Give ‘em Hell, Harry!” -- to which Truman responded, “I’m going to! I’m going to!" A plaque in Bremerton notes that this was the first occurrence of the phrase that would become forever tied to President Harry S. Truman.

Howdy-Do

The President ended his speech by paying tribute to Secretary of Labor Lewis Schwellenbach, who had passed away during the night in Washington D.C. after a short illness. After a tour of the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard at Bremerton, the president and his family boarded the governor’s yacht Olympus and headed for Seattle. When the Olympus reached Seattle, she hovered off shore for 15 minutes, while the rest of the party arrived on board the Kalakala. Once on shore at 2:00 p.m., the president made some brief remarks. Saying he was late for his talk at Memorial Stadium, he apologized for bidding the crowd “a howdy-do and goodbye.”

His talk began at 2:30 p.m., and the stadium was only half-filled. Nevertheless, the audience of 7,000 cheered when Truman took to the stage. After thanking Seattle Mayor William Devin and Governor Wallgren, he began his talk.

Power to the People

Truman’s address at the stadium was carried on a nationwide radio broadcast. In it, he called for the Northwest to arm for “the toughest kind of fight” in Congress to develop its river basins and to provide public power to benefit all. The president noted that prior to 1933, the Reclamation Act had been on the books for 30 years, but that the private power lobby had fought against it. The lobby, Truman pointed out, was against public use of the land and rivers because they claimed that there wasn’t enough industry to make it worthwhile. He noted that the growing number of new industries attracted by the Bonneville and Grand Coulee projects’ low-cost power proved their claims absurd.

Truman told the audience that Congress had already scaled back his appropriation for more funding to the Columbia Basin projects by more than two thirds, indicating that the private power lobby was still fighting progress. He urged everyone to make their voices heard in Congress, and to let them know that tying up the development of the nation’s resources would not be tolerated.

The Roaring Crowd

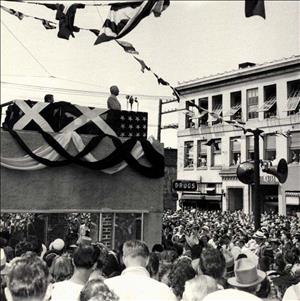

After the president’s speech, Secretary of the Interior J. A. Krug spoke briefly, and reiterated many of Truman’s points. Mayor Devin (1898-1982), Governor Wallgren, Senator Magnuson, and Emil Sick, chairman of the Washington State Press Club, also gave short statements. Mayor Devin attributed the small turnout to the speech due to many people being at work. By the time the talk was over, the workday was done, and one of the largest crowds in the city’s history lined the streets as the President and his entourage traveled through downtown Seattle. It was estimated that nearly 100,000 people gathered for over a mile to see the president.

The largest grouping was at the corner of 4th Avenue and Pike Street, where 5,000 spectators jostled for a better view. The sun was shining, and a brisk wind snapped hundreds of flags draped along the streets. Confetti flew from office windows above.

Punching Out

Before leaving the city, Truman made a brief stop at the newly opened Washington State Rehabilitation Center, near 4th Avenue and Cherry Street. Earl Anderson, director of the state department of labor and industries, presented Truman with a set of boxing gloves, and pointed out that the press had been noting how the president was handling Congress without kid gloves. “Keep on punching Congress and Republicans generally, right on the button,” said Anderson, “The do-nothing 80th Congress has stuck its chin out. Well, you know what boxing gloves are for.” Truman then met some of the men in the center who had been injured in industrial accidents.

From there, the caravan traveled to Tacoma, arriving there at just after 5:00 p.m. Truman gave a brief speech, and once again lashed out at Congress. Truman told the crowd that he wished to pay off national debts, but the Congress had just passed a tax relief package, “for the rich.” He stated that the nation, “had a surplus last year for the first time in a long time, and they are transferring part of that surplus into 1949 so far as to cover up the deficit which will be caused by this rich man's tax law.”

Not His Funeral

Once finished, the caravan sped to Olympia, for Truman’s last speech of the day. At 6:50 p.m., he spoke in Sylvester Park, and touched on many of the points he had made in speeches throughout the state. He finished by warning people that if they, “want to continue the policies of the 80th Congress, that will be your funeral.” Truman and his family spent another night at the Governor’s mansion. The next morning, they left by plane from McChord Field for Portland, Oregon. On the way, they viewed further flood damage in southwestern Washington.

Truman and his staff learned much from their western visit that they applied to his whistle-stop tour in the fall. They noted that crowd response was tremendous, although press coverage was lackluster. With less than five months to re-election, they planned their campaign.

Going into the election, Truman faced a fractured party. He had alienated southerners by supporting civil rights, and many southern Democrats supported Strom Thurmond, who ran as an Independent. But Truman’s attacks on the 80th Congress, his strong stance against Communism, and support of labor and working-class Americans resonated well with the public. In the end, Truman won the election in one of the most surprising upsets in America’s history.