On Sunday, May 19, 1912, the gangplank from Colman Dock to the Black Ball Line steamer Flyer collapses under the weight of boarding passengers, plunging more than 60 persons into Elliott Bay. Everyone is brought out of the water within 10 minutes, but 58 passengers are injured and two, a woman and child, cannot be resuscitated.

A Fast Steamer

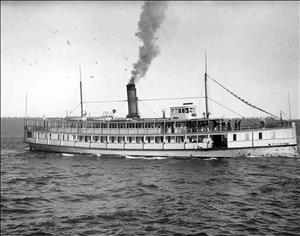

The SS Flyer was a 170-foot, wooden-hulled, inland passenger steamer built at the Johnson Shipyard at Portland, Oregon, in 1892. For years, she was the fastest Mosquito Fleet steamer on Puget Sound. At a cruising speed of 16 knots, the Flyer made the 28-mile voyage between Seattle and Tacoma in 85 minutes, four times a day. The steamer, licensed to carry 250 passengers plus freight, had an unprecedented safety record and had never known a fatality.

On Sunday, May 19, 1912, the Flyer arrived at Seattle's Colman Dock (now pier 52, the Washington State Ferry Terminal) on time at 10:30 a.m., discharging her passengers and freight. Operations there had been chaotic since April 25, 1912, when the 320-foot, steel-hulled steamship Alameda sliced 150 feet off the end of Colman Dock, toppling the 100-foot clock tower into Elliott Bay and exposing the passenger waiting room beneath the dock's dome. In the interim, Mosquito Fleet steamers had to make do until the wrecked portion of the dock could be completely repaired.

An Unusual Docking Situation

The Flyer had been moved up the pier to a gangplank ordinarily used to load and unload freight and livestock. Passengers usually boarded the steamer's boat deck across a gangway from the waiting room on the upper level of the dock. Now, because of the damage, passengers were directed downstairs to board at a former freight slip.

The freight gangplank, 80-feet-long and eight-feet wide, was permanently attached inside the dock with large iron hinges. The outer end was supported by chains and could be raised and lowered according to the tide by a worm gear mechanism. Due to a minus tide on Elliott Bay, the gangplank, positioned at a low downward angle, would not reach the Flyer's deck, so a smaller gangplank was used to bridge the gap between the steamer and the larger gangplank. On this morning, the distance from the dock to the water was nearly 20 feet.

At about 11:00 a.m. the Flyer began loading for Tacoma. More than half the passengers had crowded onto the gangplank and then onto the steamer when suddenly the outer end collapsed, plunging more than 60 persons headlong into the polluted water of Elliott Bay.

The Accident

Captain Everett. B. Coffin, seeing the mishap, immediately sounded the emergency signal, four blasts of the Flyer's steam whistle. Then he ordered all hands to throw overboard life preservers, wooden deck chairs and anything that would float giving the victims something to cling to until rescued. Several of the Flyer's crew donned life preservers and jumped into the water to assist struggling victims. Meanwhile, help was arriving from all over the waterfront. Within minutes, Railroad Avenue (now Alaskan Way) was crowded with ambulances, police cars, taxicabs and automobiles.

The steamers Puget and Rosalie lowered lifeboats and began picking up survivors. The fireboat Snoqualmie, moored nearby, raced to the rescue as did the motor launch Skeeter and several other small craft. Newton Johns, bootblack at the Colman Dock shoeshine stand, jumped into the water and was credited with saving 10 lives. Bystanders on Colman Dock threw lifelines into the water and dragged survivors toward the end of the collapsed gangplank, enabling them to climb to safety. Several passengers clung to pilings while others held onto floating objects or tread water until rescued by the boats. Within 10 minutes, everyone had been fished out of the bay and rushed to nearby hospitals.

Immediately after the accident, Bruce F. Morgan, manager of Colman Dock, contracted with the Heffernan Dry Dock Company on the East Waterway at Hanford Street, to dispatch a scow with a deep-sea diver to search the bottom of the harbor for bodies near the scene of the accident. The diver, Otto C. Peterson, searched the murky water for two hours and covered more than 100 square feet, sometimes on his hands and knees, but was unable to find more victims. The authorities were confident that all the passengers involved in the accident had been accounted for.

Lost: a Young Mother and a Little Boy

The official toll from the tragedy was 58 passengers injured and two drowned, Florence E. Learnerd, age 30, and George Bruder, age 3. The majority of the injuries were cuts and bruises. However several survivors arrived at City Hospital unconscious and had to be revived. A pulmotor (or resuscitator) had been rushed to the hospital from the mine rescue station at the University of Washington. This new device, the only one of its kind in Seattle, was responsible for saving at least four lives including Jack Learnerd, the 3-year-old son of victim Florence Learnerd. But efforts to revive Bruder and Learnerd with the pulmotor proved unsuccessful.

On May 21, 1912, a coroner's inquest was convened to investigate the accident. The inquest found the direct cause of the gangplank's collapse was faulty equipment. The gears used to raise and lower the gangplank disengaged allowing the outer end to fall. The reason for the failure was that the worm gear and cogwheel had become misaligned and did not properly mesh. The following day, the corner's jury declared that the accident leading to the deaths of two people, was "due to the carelessness and negligence of the Colman Dock Company and its employees." The evidence, however, was insufficient to warrant criminal prosecution.

The tragedy seemed to be the result of a series of unfortunate circumstances inadvertently caused by the Alameda's collision with the dock three weeks earlier. The dock had been widened so it was necessary to make the gangplank about eight feet longer to reach the ships. The increased length placed additional stress on a poorly designed mechanism whose gears, instead of being held in place by a steel frame, were attached to large wooden supports fastened to the outer edge of the pier with spikes. Increased leverage and torque twisted the supports out of position causing the gears to disengage and the gangplank to fall.

New Regulations

As a result, new regulations were established requiring the overhaul of all dock machinery, the installation of steel supports and braces, and break mechanisms for the gears. In addition, all dock machinery would be subject to weekly inspections by the Engineer of Public Service Commission and the dock managers were instructed to revise their loading procedures, prohibiting passengers from crowding the gangways.

One week after the accident, the Flyer was removed from the Seattle-Tacoma run she had dominated for 30 years, replaced by the Black Ball Line's 206-foot, steel-hulled steamer Chippewa. The Flyer, rebuilt and renamed the Washington in 1918, continued in service around Puget Sound until 1929 when she was stripped and burned on Richmond Beach for scrap metal.