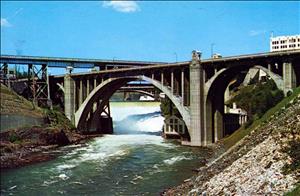

On November 23, 1911, Spokane's third Monroe Street Bridge opens. Considered a marvel of beauty and functionality, it is the largest concrete-arch bridge in the United States. A major transportation link, the bridge becomes a "revered symbol" of Spokane ("Bridging the Past ...," Spokesman-Review), and “Spokane’s premier character-defining landmark” (Holstine and Hobbs). The bridge is designed and constructed by Spokane city engineers, and the elaborate ornamentation is provided by the Spokane firm of Kirtland Cutter and Karl Malmgren.

The first bridge to span the Spokane River Gorge was a rickety wooden affair completed in 1889 by the Spokane Cable Railway Company in a partnership with the city and private interests. It burned down in 1890 and was replaced with a steel bridge able to accommodate power wires for streetcars and overhead lighting. This bridge vibrated badly, and in 1905 a National Good Roads Association consultant declared it unsafe, although it continued to be used. Even Ringling Brothers Circus elephants were said to have balked at crossing it. The second Monroe Street Bridge was in use for barely 20 years.

In 1909 Spokane City Engineer John Chester Ralston completed the design and specifications for the replacement bridge. The new bridge was a 281-foot monolithic concrete span with main piers met by graceful arches at either end. Its continued location at Monroe Street required crossing a gorge 140 feet deep and 1,500 wide, no easy task. High water flow of enormous speed presented additional construction problems. Furthermore, on July 21, 1910, a severe windstorm destroyed the temporary wooden falsework, adding cost and delay.

Possibly unjustly, the City Council removed Ralston for alleged incompetence and promoted his assistant, Morton Macartney, to his position. To complicate matters further, officials in Cuyahoga County, Ohio, asserted that Ralston “essentially stole the bridge design, which is nearly identical to that of the Rocky River Bridge in Cleveland” (Spokesman-Review, September 17, 2005), and sued the City of Spokane, unsuccessfully.

A most beloved feature of the Monroe Street Bridge was the ornamentation provided by the firm of Kirtland Cutter and Karl Malmgren. Its exact conception and evolution are “steeped in legend” (Holstine, Nomination, Item no. 8, p. 5). The original design for the four pedestrian lookout pavilions included an Indian and canoe motif. The only portion of the design to be implement included eight life-sized bas-relief concrete bison (or bovine) skulls, four facing out and four facing in, on the covered wagon-shaped lookout pavilions. Ralston, the original engineer, referred to them as ox skulls. Spokane architectural historian Nancy Gale Compau says Cutter and Malmgren “used a real skull to sculpt the pavilions’ buffalo skulls symbolizing the West” (Compau, 1), and most published accounts refer to them as bison or buffalo skulls.

Regardless of their exact nature, “The wagon pavilions and skulls are among the most distinctive of any bridge ornamentation in the Northwest” (Holstine and Hobbs). Cutter and Malmgren also designed guardrails with a chain motif “that gave a feeling of strength and continuity. From the bridge, people could stop and admire not only the spectacular falls but also Cutter’s power station [Washington Water Power] standing confidently beside it.” (Matthews, 259) In 1920 a jury of West Coast architects listed the Monroe Street Bridge as one of the ten most notable examples of Spokane architecture.

Unlike many large civil engineering projects, the spectacular and functional 1911 Monroe Street Bridge was truly a home grown achievement: City engineers designed it and supervised its construction, a local architectural firm provided ornamentation, and Spokane day labor crews built it. More than 3,000 people attended the opening on November 23 of that year.

However, Spokane had little time to enjoy the aesthetics of the new bridge, for in 1914, the Union Pacific Railroad built a steel viaduct diagonally across it. Not until 1973, in preparation for Spokane’s environmental world’s fair, Expo ’74, was it removed. The Monroe Street Bridge was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1976 and on the Spokane Register in 1990.

By the 1990s the venerable bridge was deteriorating so badly that frequent repairs would no longer suffice to keep it viable. A new bridge was needed, but “saving [the original] wasn’t always the idea; in fact, for quite some years the idea was to replace the current bridge” (Compau, 1).

Fortunately, community consensus eventually favored a replica or rehabilitation rather than a new design. In January 2003, the bridge was closed for restoration under the engineering and construction management firm of David Evans and Associates. Spokane watched, fascinated, as the old bridge was dismantled and the new rose in its place, to open in September 2005. The new bridge looks like the old, with the same overall design and the Cutter and Malmgren ornaments faithfully replicated. The improved pedestrian walkways still provide unsurpassed viewing points for the spectacular falls of the Spokane River.