The Washington Forest Protection Association (WFPA) was established in 1908, and for its first 50 years was known as the Washington Forest Fire Association (WFFA). The WFFA grew quickly in its early years, particularly in 1917, the year of the enactment of Washington state’s Forest Patrol Law. The WFFA was originally a fire-prevention and fire-fighting organization, and fire was considered the enemy. But not long after the WFFA reincorporated as the Washington Forest Protection Association (WFPA) in 1958, that began to change. By the 1960s it was becoming known that aggressive fire protection could be detrimental to forest health and that some controlled fires were actually beneficial to the forest ecosystem. At the same time, more public awareness of environmental issues resulted in an increasing number of laws and forest regulations affecting forest use. In order to meet these changes, the WFPA evolved into more of a political organization to better respond to its members needs. In 1986 and 1987 the WFPA helped create the Timber Fish Wildlife (TFW) Agreement, which has since been an effective tool in resolving forest management issues in the state. The Washington Forest Protection Association celebrated its 100th anniversary on April 6, 2008.

Washington Forest Fire Association

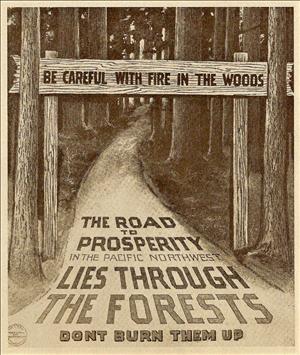

Fire has always been a natural part of the Northwest’s environment, but when non-Indian settlers began arriving in the last half of the nineteenth century in what became Washington state, fire danger increased. Logging and milling soon became the backbone of Washington’s economy, and when fires struck it was often catastrophic for business. In the state’s early years, there was little that could be done to effectively fight a large fire.

In September 1902 the Yacolt Burn, the largest forest fire in recorded state history to that point (and for more than a century thereafter), burned more than 370 square miles of timber worth up to $30 million in 1902 dollars (more than $600 million in 2008 dollars). This was the spark that galvanized people into action and led to the first organized efforts to establish fire protection in the state. In 1905 the Legislature established a State Board of Fire Commissioners, which appointed a State Forest Fire Warden and deputies. $7,500 was appropriated to fight fires for the biennium of 1905-1907, but funds ran out during the summer of 1905. The commission appealed for assistance to private timber interests, which owned vast tracts of land, and raised a total of $10,300 to fight fires in 1906.

In 1907 and 1908, major timberland owners in Western Washington met to discuss organizing a fire protection association. Early in 1908 leaders in the timber business, including George S. Long (1853-1930), General Manager of Weyerhaeuser Timber Company, mailed 800 letters to timberland owners inviting them to form a voluntary association to suppress forest fires. Twenty-two companies responded and incorporated the Washington Forest Fire Association (WFFA) on April 6, 1908. The life of the association was set at 50 years, a common custom in 1908. The five incorporators of the WFFA were George Long of the Weyerhaeuser Timber Company, E.G. Ames of the Puget Mill Company (now Pope and Talbot), Michael Earles of Puget Sound Mills and Timber Company, T. Jerome of the Merrill & Ring Lumber Company, and D.P. Simons Jr., who became the first chief fire warden of the WFFA. George Long was the WFFA’s first president, and served in this position until March 1930.

The WFFA’s first office was located in the Colman building on 1st Avenue in Seattle. The association recruited 126 members in its first year, and assessed its members one-half cent per acre of land patrolled. Chief Fire Warden Simons organized a force of 75 men, each of whom was equipped with an axe, a planter's hoe, and a 10-quart water bag (for the fire crew). Seven fire districts were established, stretching east from the coast to the Cascades, and north from the Columbia River to the Canadian border.

The Enemy Is Fire!

In August 1910 more than 1,000 fires struck Idaho and Montana, destroying three million acres and killing 85 people. Large fires also struck Washington state that summer. This resulted in a policy of aggressive fire protection. Fire became the enemy. In 1911 the Legislature enacted a new fire law making prevention of forest fires a first priority and full suppression of fires next in priority, and increased the biennial appropriation to fight fires to $30,000 for the 1911-1913 biennium. The WFFA put more men in the field, and began issuing permits for slash burning (disposal of wood remnants left over after logging). In May 1913 the WFFA began a system of logging camp inspections designed to educate loggers and owners on how to reduce the risk of fire (this was not popular with the loggers), and also to identify and map where logging operations were being conducted, which enabled rangers to more effectively patrol for fires.

In 1917 the Legislature enacted the Forest Patrol Law, which required forest landowners to provide fire protection against the spread of fire. Owners unable or unwilling to do so received protection from the WFFA and were assessed 2 cents an acre by the State Forester for such protection. Under an agreement between the WFFA and the State Board of Forest Commissioners, the WFFA patrolled some 600,000 acres belonging to non-members that first year. But as a result of the new law, membership jumped in the WFFA by nearly 75 percent in 1917, from 198 to 346 members during the year. The new law also led to more organized field operations, and in 1918 the WFFA patrol force passed 100 for the first time.

The WFFA’s patrol force continued to grow rapidly during the early 1920s. But large fires continued to plague Western Washington, destroying hundreds of thousands of acres and in some cases entire communities, such as Lindberg (Lewis County) in 1918, and Monohon (King County) in 1925. The WFFA responded with a variety of techniques to meet the challenge. In 1923 the association began using portable gasoline pumps to fight fires, and later in the decade bought its first truck and tractor to fight fires. Also in 1923, writers for the U.S. Forest Service published papers showing the relationship between low relative humidity (under 35 percent) and fires, a correlation that had not previously been understood, but one that would a decade later lead to logging operations being suspended in periods of particularly hot or dry weather. And by the late 1920s, fire lookout houses and lookout towers were being built and staffed by rangers atop various mountain peaks throughout western Washington. In addition to providing great views for looky loos, the houses and towers enabled rangers to spot fires early in more remote locations and thus to alert firefighters to the threat more quickly, helping to curb fires before they got out of hand.

CCC Camps and Tree Farms

The Great Depression struck in the autumn of 1929, and the Depression directly impacted the WFFA during the early 1930s. Homeless and otherwise displaced people began deliberately setting fires and then gallantly offering to help firefighters put it out -- providing they were paid for their services. This problem continued for several years. Then, in 1933, President Franklin Roosevelt (1882-1945) established the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), a work relief program designed to combat unemployment. CCC camps sprang up throughout Western Washington, staffed by young men (usually age 18 to 25) who augmented the WFFA’s staff for firefighting, thereby eliminating the financial incentive for an arsonist to start a fire. But the “CCC boys” (as they were known) also built thousands of new miles of road and trails into the woods, built new lookout towers and lookout houses, planted trees, and provided other services to the WFFA during the decade. The CCC program ended in 1942 with the coming of World War II.

The value of reforestation -- planting new trees to replace ones logged -- had been recognized as far back as the early 1920s, and some efforts were made at reforestation in the 1920s and 1930s. But it was the 1940s that saw the first large steps taken toward reforestation. In June 1941, Weyerhaeuser Timber Company dedicated the nation’s first tree farm near Montesano (Grays Harbor County). The 130,000-acre farm was named the Clemons Tree Farm after local logger Charles Clemons. And in January 1946, Washington state’s first forest practices act took effect, which required the state’s loggers to plant trees to replace the ones they had harvested. The law also applied to private landowners.

In April 1947 the State Division of Forestry notified the WFFA that after the 1947 fire season it would no longer renew the annual patrol contract to protect state-assessed lands as it had since 1917. In 1948 the WFFA entered into a contract with the State in which the State provided the patrols on WFFA membership lands. This was a big change, but it did not impact the WFFA as much as it might have a few years earlier, because by this time local fire-fighting associations (such as Rue Creek and Trap Creek) were developing. These smaller associations were interested in having fire-fighting protection directly available within their immediate boundaries in the event of fire rather than having to risk waiting hours for it to arrive from another location, and the WFFA provided this protection through agreements negotiated with these associations.

Washington Forest Protection Association

In January 1958 the WFFA reincorporated as the Washington Forest Protection Association (WFPA). By coincidence, a year earlier the Legislature had created the Department of Natural Resources (DNR), which consolidated several existing state agencies responsible for the state’s forest practices into the DNR, with the goal of more effectively managing state land. The DNR also took control of forest fire prevention and suppression on public and private lands. These changes were a harbinger for a series of sweeping changes that would transform the newly minted WFPA into a far different organization than the WFFA had been. The new WFPA would evolve from a fire protection organization into one that would be far more involved in legislative matters and public information projects than its predecessor.

The changes were relatively subtle during much of the 1960s, and during the decade the WFPA continued to devote a large amount of its effort toward fire prevention. The 1970 WFPA Annual Report noted that the 20-year average between 1950 and 1969 of total number of acres burned in fires on association land was 4,480 acres burned per year. This was a 96 percent decrease from the 15-year period of 1920 to 1935, when the annual average of acres burned exceeded 120,000. Yet the average of total number of fires per year remained largely unchanged at nearly 800, providing solid proof of the association’s success in fire prevention and firefighting techniques as well as advances made in firefighting technology over the course of half a century.

But by the 1960s a shift was starting to occur in foresters’ attitude toward fires. Foresters were beginning to realize -- and were able to establish -- that policies of aggressive fire suppression were actually detrimental to forest health and productivity. By the end of the twentieth century, federal land managers would be employing prescribed burning to replicate the historic role of fire in forest ecosystems and to reduce the amount of fuel that had built up over decades of preventing forest fires.

Transition

Meanwhile the Washington Forest Protection Association's transition from a fire prevention organization to more of a political organization was accelerating. One of the first major changes took place in 1966 when the WFPA reorganized and became a statewide organization. With this change, the WFPA at the end of 1966 represented 61 percent of private forestland in Western Washington, and 33 percent in Eastern Washington. The reorganization was the result of requests by forest landowners in the state for the WFPA to take on the additional job of determining the consequences of public policies which during the 1960s were beginning to have an impact on forestlands, and to provide a liaison between WFPA members and the public and governmental agencies in Washington state. This was a prescient step by the WFPA, because a rapid increase in court decisions and environmental laws passed in the 1970s would have an enormous impact on the state’s forest landowners and necessitate a far more activist role by the WFPA in addressing these laws.

In 1971 the State Environmental Policy Act (SEPA) was enacted. SEPA sought to maintain and improve environmental quality by requiring governmental agencies to give proper consideration of environmental issues when making decisions on actions that might affect the environment. Additional federal regulations such as the Clean Water Act and the Endangered Species Act of 1973 soon followed. The result was “a bewildering array of fractionated, uncoordinated regulations administered by ... many governmental entities” (1973 WFPA Annual Report, p. 8). As a result, the Washington Legislature passed a new Forest Practices Act in September 1973, designed to regulate all forest practices on state and private land, including logging and its impact on the environment. The new act also established an 11-member Forest Practices Board. Final regulations took effect on July 1, 1976. Later rules were added to cover scenic vistas, archeological resources, and threatened and endangered species.

But the new regulations did not solve the problem. Competing interests fought for attention and influence before the Forest Practices Board, resulting in an adversarial and contentious environment. Unhappy stakeholders often simply filed a lawsuit. Even when the board issued a decision, it was often challenged and sometimes overruled by a court.

Stewart Bledsoe and TFW

It was during this period that Stewart "Stu" Bledsoe (1922-1988) became the WFPA’s executive director in 1977. This was a time of considerable change in the WFPA: The association had again reorganized in November 1975 and had created five committees -- Forest Management, Forest Taxation, Governmental Affairs, Land Use, and Public Information -- to handle the issues facing the WFPA. And in 1978 the WFPA moved its main offices from Seattle to Olympia in order to be closer to the state capital and more effectively deal with its increasingly political role in forestland issues. Bledsoe was a strong leader in managing the WFPA through these changes, and also in confronting the challenges facing the WFPA and its forest landowners in the 1970s and 1980s that resulted from a multitude of environmental regulations and court actions.

By the mid-1980s frustration with the constant friction and legal battles between natural resource agencies, tribes, environmental groups, and forest landowners seemed destined to continue on into infinity like a madly spinning hamster wheel to nowhere. Then, in the spring of 1986, Billy Frank of the Nisqually Tribe made a proposal that would change everything: an alternative dispute resolution for forest practices. This would lead to the Timber Fish Wildlife (TFW) Agreement in 1987.

Timber Fish Wildlife, or TFW, changed everything when it came to resolving forest management issues. Changes in forest practices rules were now negotiated among parties in a more neutral setting, one designed to encourage mutual respect and cooperation, rather than being argued in an adversarial proceeding before a commission or court. Yet the goals of any TFW proceeding were complementary in that they provided for both the environment and a healthy forest industry. Bledsoe was a leader in the six-month long, 60-meeting effort that resulted in the TFW Agreement. The agreement was announced on February 17, 1987, and it received unanimous approval from both the Legislature and the Forest Practices Board. In 1988 state and private natural resource managers began working with Indian tribes and environmental groups to implement TFW, and in the 20 years since it has proven to be a successful method for dispute resolutions involving natural resources.

Bears, Owls, Fish, and Forests

The WFPA’s efforts at forest protection at the forest level (as opposed to the political level) also continued. In 1985 the WFPA developed its Supplemental Bear Feeding Program. The program was created under the direction of WFPA Animal Damage Control Program Supervisor Ralph Flowers in order to curb bear damage to trees. Black bears, in particular, strip the bark off of maturing trees in the early spring in search of nourishment before berries and other food becomes available. The Supplemental Bear Feeding Program minimized bear damage to trees by providing special food pellets to these animals, and enabled forest owners to control bear damage without having to remove the animals from the area. The program grew rapidly: In its 10th year (1994), more than 310,000 pounds of pellets were used to feed the bears at nearly 600 feeding stations scattered throughout Western Washington.

The WFPA had its hands full in the early 1990s with the spotted owl. The U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service listed the spotted owl as an endangered species in 1990, and the following year the Department of Natural Resources set aside large areas of land for owl habitat. This resulted in a large reduction of Washington state’s timber harvest, and the WFPA spent considerable time for the next several years hammering out forest practice rules to provide protected habitat for the spotted owl while at the same time providing for timber harvesting in areas that did not threaten the owl. New forest practices rules for the spotted owl took effect in Washington in July 1996.

The WFPA’s focus shifted from land to water in 1997 when formal negotiations began in the TFW forum to develop a state-based plan for improving fish habitat and water quality protection on private forestland. This resulted in the Forests & Fish Agreement, which was signed into law by Governor Gary Locke (b. 1950) on June 7, 1999. A particularly significant achievement, the law increased buffers of trees along 60,000 miles of streams on state and private forestland, improved road maintenance standards, and increased protection for steep and unstable slopes. The Forest Practices Board adopted permanent rules to implement this agreement in 2001.

On June 5, 2006, Washington Governor Christine Gregoire (b. 1947) signed the Forests Practices Habitat Conservation Plan (FPHCP) into law. This plan is a 50-year contract between the state and federal government that assures private forestry landowners in Washington state that their forest practices meet the requirements for aquatic species that are set forth in the Endangered Species Act passed by the U.S. Congress in 1973. With the passage of this law, the WFPA was finally achieving its long-sought goal of regulatory predictability.

To the Future

In March 2008 Governor Gregoire issued a proclamation declaring March 11, 2008, as “Washington Forest Protection Association’s 100th Anniversary Celebration,” and on April 6, 2008, the WFPA celebrated its 100th anniversary.

Perhaps the biggest (and in some ways ironic) lesson learned in the association’s first 100 years was that fire is not always the enemy, and actually plays an important role in a healthy ecosystem. We now know that active forest management -- thinning small trees and clearing brush, followed by controlled burning -- not only reduces the risk of a major fire but also restores ecosystem health and improves habitat quality.