The North Cascades Conservation Council has, since 1957, been an unchanging agent of change. Turning out members for hearings, going to court, deploying hiking guides and picture books, it has helped preserve 2.21 million acres in Washington state between Stevens Pass and the Canadian border as parks, recreation areas, and wilderness area. It is, however, never satisfied and always wants more land set aside. The outfit is hard to love, impossible not to admire.

Small But Hard-Hitting

The North Cascades Conservation Council, founded in 1957, had already pushed successfully to create a national park by the time the environmental movement burst into America’s national consciousness more than a decade later.

The N3C, as it is popularly known, is with us still -- headed by some of the same directors present at its creation -- and lately embarked on a new campaign to push out boundaries of the 43-year-old North Cascades National Park in Northwest Washington. The original Board of Directors included these founders:

-

Polly Dyer, Seattle

-

Patrick Goldsworthy, Seattle

-

Phil Zalesky, Everett

-

David Brower, Berkeley, Calif.

-

Grant McConnell, Stehekin

-

Emily Haig, Seattle

-

Charles Hessey, Naches

-

Joseph Collins, Spokane

-

John Warth, Seattle

-

Una Davies, Oregon

-

Jack Stevens, Manson

-

Chester Powell, Seattle

-

Yvonne Prater, Ellensburg

-

Dave Simons, Oregon

-

Ray Courtney, Stehekin

-

Rod O’Connor, Bellingham

-

Rick Mack, Sunnyside

-

Jack Wilson, Cashmere

-

Art Winder, Seattle

-

Leo Gallagher, Tacoma

-

Ned Graves, California

-

Philip Hyde, California

-

Neva Kerrick, Seattle

-

Paul Gerhardt

The group has been an unchanging agent of change. It is insular, never bothering to put election of its board of directors to a membership vote. (The initial fear was of a stealth takeover by timber companies.) It has parted company with some supporters who wouldn’t toe the line on such issues as closing the upper part of the Stehekin River road, which starts at Lake Chelan and extends into the park.

In a half-century, the N3C has scrapped with government agencies at all levels. It has litigated against the National Park Service, after fighting to have the NPS put in charge administering 694,000 acres of national park and two national recreation areas in America’s “Wilderness Alps.”

“The North Cascades Conservation Council, as most of us know, is a small but hard-hitting group with a reputation for mixing it up with politicians and bureaucrats that threaten the values we hold dear,” N3C President Marc Bardsley wrote a few years back in its feisty journal The Wild Cascades (Winter 2003-2004, p. 3)

If you want a sense of how far conservation has come in the Evergreen State, take a mental trip back to the late 1950s.

Just What Do You People Want?

The state’s national forests were treated as tree farms for the timber industry. The U.S. Forest Service was mapping out logging roads into remote, pristine valleys. The hostile supervisor of the Wenatchee National Forest greeted a delegation from outdoor clubs with the words: “Just what do you people want?” A Seattle Times editorial mocked opponents of a proposed tramway at Mount Rainier as “birdwatchers and mountain climbers” (Harvey Manning, Wilderness Alps, p. 126).

“I so well remember in the mid-1960s, when I was climbing a lot and just becoming aware of what was out there -- and what was being lost ... and it all seemed so hopeless then,” Brock Evans, a longtime conservation lobbyist in both Washingtons, reflected recently. “That’s when I first heard about N3C, and I joined up. They were then the fightingest and scrappiest outfit around, on behalf of places I loved and cared about. To me, then and since, on the issues I know about, N3C has always been of the finest exponents of ‘endless pressure endlessly applied’ anywhere” (Brock Evans, e-mail, February 1, 2011).

Glacier Peak Wilderness

As a Fairhaven Junior High student in Bellingham, Washington, this writer witnessed in his school auditorium one of the N3C’s first battles. The U.S. Forest Service proposed an octopus-shaped “rock and ice” Glacier Peak Wilderness Area, extending out ridges but opening to logging the great valley of the Suiattle River that curls around Washington’s “hidden” volcano, 10,541-foot Glacier Peak.

A surprise was in store at the first hearing. The N3C mobilized conservationists -- where did these people come from? -- and they proved a contentious lot. The executive director of the Bellingham Chamber of Commerce was questioned from the floor and forced to acknowledge that his anti-wilderness statement was ghostwritten by the Puget Sound Pulp & Timber Company.

Birdwatchers v. Birdwatchers

The “birdwatcher” moniker became a rallying cry. Harvey Manning (1924-2006) started writing a column for “The Wild Cascades” under a pseudonym “The Irate Birdwatcher.” At the Glacier Peak hearing, one industry speaker applied the label, and was on the receiving end of an unforgettable retort: “You’re the birdwatcher, mister. The bird you’re watching is the eagle on the dollar bill” (Connelly, personal obvservation).

What difference can citizens make? The answer, with imagination and persistence, is a heckuva lot. “They (N3C) were the model, I know, when we -- living in Corvallis at the time -- set out to create an Oregon Cascades Conservation Council,” said former U.S. Rep. Jolene Unsoeld, D-Wash (Unsoeld, interview, January 28, 2011).

Words and Pictures

The written word and the camera lens were the N3C’s weapons in early wilderness wars.

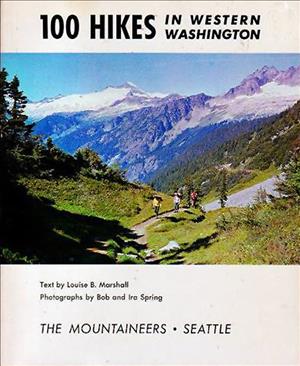

The “Wilderness Alps” were introduced to the nation in an exhibit-format book The North Cascades, written by Harvey Manning and Tom Miller, both N3C activists. The Sierra Club went national with a book The Wild Cascades: Forgotten Parkland. Manning wrote the text, and the subsequent 100 Hikes books. Dr. Fred Darvill (1927-2007), a sometime N3C board member, penned a Sierra Club pocket guide to the North Cascades and later a beautiful guidebook to the Stehekin Valley.

The Sierra Club’s executive director and N3C board member David Brower (1912-2000) took his family on a horseback trip to remote Park Creek Pass, and produced a film, The Wilderness Alps of Stehekin.

North Cascades National Park

U.S. Interior Secretary Stewart Udall (1920-2010) came West for the 1962 Seattle World’s Fair, later adjourning to a beach party at the Bainbridge Island home of Seattle attorney Irving Clark Jr. N3C President Dr. Pat Goldsworthy (1919-2013) was invited. “I told him beforehand, ‘Stuart Udall is a busy man.’ Let him relax,’” Clark later told a reporter. Goldsworthy, however, positioned himself just inside the door, collared Udall, spread out maps, and produced stunning photos.

The North Cascades National Park would be one of four parks created during Udall’s tenure at Interior. President Lyndon Johnson (1908-1973) signed the North Cascades Act, creating the park complex as well as setting aside nearly one million acres in the adjoining Glacier Peak and Pasayten Wilderness Areas.

The N3C, of course, was not satisfied. It wanted more land preserved. It set to work knocking down proposals for “industrial tourism” in the park complex, such as a tramway up Ruby Mountain and a big car campground at Roland Point, both in the Ross Lake National Recreation Area.

Raising a Ruckus

Manning was M3C’s contentious, confrontational public voice, applying labels with abandon. He took out after “the Confederacy of Chelan County,” attacked motorcyclists use of the backcountry and mocked national forest supervisors as “Logger Larry” and “Dandy Andy.” (Manning, Wilderness Alps, p. 266)

He stirred up a ruckus by proposing that Washington’s State Route 20, the North Cascades Highway -- or “North Gollydarn Highway” in Manning prose -- be kept open for a time but then permanently closed. It was the ultimate example of what some N3C activists have called “re-wilding” of land now reached by roads.

Not Raising "High Ross" Dam

The N3C also produced quiet heroes, none greater than Joe (1915-2008) and Margaret Miller. The Millers worked for two decades, using native species, to re-vegetate trampled and denuded meadows at Cascade Pass, a scenic high point of the North Cascades National Park.

The couple’s greatest service, however, came during debate over whether to let Seattle City Light raise the height of Ross Dam on the Skagit River by 125 feet. The project would have pushed the reservoir farther over the Canadian border and inundated 10 square miles of river bottom in British Columbia. On the U.S. side, “High Ross” would have inundated six miles of the Big Beaver Valley in the Ross Lake National Recreation Area.

The Millers carried out a pioneering survey of ecosystems and the 800-year-old Western red cedar forests of the Big Beaver. A City Light-sponsored study claimed to have found “whole valleys of Western red cedars in other drainages” (The Wild Cascades, Winter 2005-2006. p. 11)

The Millers correctly analyzed the valley as unique and non-replicated. They identified 240 plant species native to the area, 21 not previously known to exist in the park complex. Ross Dam was not raised. In 1982, the city of Seattle and British Columbia hammered out an 80-year agreement under which the province supplies an equivalent of the electricity that would have been generated by the higher dam.

Opposing the Open Pit

“High Ross” was a big battle. So was a lengthy struggle against Kennecott Copper’s proposed half-mile-wide open-pit mine on Miner’s Ridge, deep in the Glacier Peak Wilderness and renowned for vistas of its namesake peak.

“An Open Pit Visible From the Moon” blared a Sierra Club-sponsored ad masterminded by David Brower, which ran in The New York Times and the Los Angeles Times. U.S. Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas (1898-1980), a longtime N3C friend, traveled to the Suiattle River to lead a protest hike.

One image endures from the open-pit battle. Dr. Fred Darvill bought a share of Kennecott Copper Co., and traveled to the company’s stockholder meeting in New York. Jaunty in an Errol Flynn mustache, he held loft a photo of Glacier Peak reflected in Image Lake (just west of the mine site). The picture made news wires across the country.

Keeping Up the Pressure

N3C kept up the pressure, decade after decade. The million-acre 1984 Washington Wilderness bill created five new wilderness areas between Stevens Pass and the Canadian border, embracing wild lands from low-level forests of the Boulder River to lofty 10,778-foot Mt. Baker.

The private wilderness in-holding where Kennecott planned to build its mine was finally acquired by the U.S. Forest Service as part of legislation that created the Wild Sky Wilderness Area.

Back in 1963, the N3C put its dreams to paper with a map and proposed boundaries for a future North Cascades National Park, a Chelan National Recreation Area, and an Alpine Lakes Wilderness area in the “land of 600 lakes” between Washington’s U.S. 2 Stevens Pass and I-90 Snoqualmie Pass (Manning, Wilderness Alps, p. 164). It is fascinating to compare this wish list with what’s actually been achieved in the years since. The 393,000-acre Alpine Lakes Wilderness (created in 1976) is, for instance, considerably larger than what the N3C was proposing.

The transformation of land management is most striking between Stevens Pass and the Canadian border. The new 103,000-acre Wild Sky Wilderness in Snohomish County, created in 2007, is the 12th large parcel of mountain wild land to be protected since 1968. The total acreage comes to 2.4 million acres.

Fighting the Good Fight

The N3C remains at work on multiple fronts. Its fight to close the upper Stehekin Road pits the group against a longtime ally, ex-Gov. Dan Evans (1925-2024), a key architect of the Washington Wilderness bill.

N3C is also is fighting to prevent (or at least minimize) logging on Blanchard Mountain, where mountains reach the sound. It has pressured the state Department of Natural Resources to rein in off-road vehicle use in the Reiter Forest above the Stevens Pass Highway. It is trying to kill legislation that would green light the killing of wolves: Canis lupus has recently reappeared, along with wolverines, in the North Cascades.

N3C is revisiting the achievement that caused its creation: 2.3 million acres are by no means enough.

Indestructible and Still Going

In 2009, The Seattle Times ran a front-page story showing two 1957-vintage N3C board members, 89-year-old Polly Dyer (1920-2016) and 90-year-old Pat Goldsworthy (1919-2013), beside the Baker River at the North Cascades National Park boundary. They were part of the N3C's American Alps Legacy Project: Its aim, naturally, increase the national park by 300,000 acres -- and bring the political park boundaries of 1968 in line with contours of the land.

The N3C seemed indestructible. A recent edition (Summer/Fall 2010) of The Wild Cascades showed an 88-year-old Margaret Miller, now legally blind, on a hike up to Cascade Pass in the company of Polly Dyer.

The outfit that helped pioneer exhibit-format books and hiking guides continued working to keep up with the times. Another heading in a recent journal: “Saving the Cascades with Social Media” (The Wild Cascades, Summer-Fall 2010, p. 4).