Beginning about 7,000 years ago, the climate become more like the modern era, relatively wetter and cooler than in the previous 3,000 years. With this change the ecosystems of the Puget lowland began to look more like their modern counterparts, with western red cedar, Douglas fir, and western hemlock as the dominant, large conifer trees.

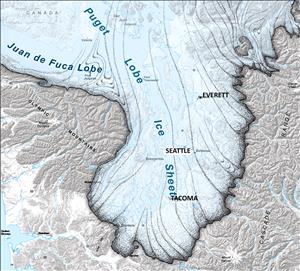

The Puget Lobe

During the last ice age a great glacier, known as the Puget lobe of the Cordilleran Ice Sheet, spread across the land. The 3,000-foot-thick ice slab slid out of Canada between the Cascade and Olympic Mountains and passed through what is now Seattle about 17,600 years ago. The ice continued south, advancing about a mile every three years, and reached the latitude of Olympia, where it stalled for a few hundred years, then began to retreat, or melt, back to the north. By about 16,500 years ago, the area around Seattle was ice-free and by 14,900 years ago the glacier had retreated out of the Puget lowland.

Although the Puget lobe persisted in this region for a relatively short geologic time span, it had a profound influence on the landscape and the plants that returned. As the ice advanced across the land, it deposited layers of sediment, leaving behind an area mostly devoid of hard rock. Instead, relatively soft sediments covered the ground. In addition, the ice and the rivers of water that flowed beneath it sculpted the sediments, leaving behind the complex topography of the Puget lowland.

When the Puget lobe was present the landscape was mostly devoid of life. Microscopic and some larger life forms could have survived on the icy surface, but otherwise there were none of the plants or animals that dominate the modern environment. After the ice retreated to the north, the landscape began a slow change. The land itself was mostly barren, having been wiped clean of life during the ice age.

Life Returns

Several studies have been conducted that explore the return of plants to the landscape. All of them rely on the analysis of pollen, spores, and microfossils collected from layers of mud. Plants produce pollen and spores for sexual reproduction. Production can be copious, as anyone who suffers in the spring when yellow "dust" descends from the abundant trees around us can attest. Not only is pollen abundant and spread widely by wind and water, but the grains are very resistant and thus persist in the fossil record. The local studies were conducted at Battle Ground Lake, Orcas Island, and Lake Washington.

Battle Ground Lake is the southernmost site studied, and although located out of the Puget lowland, it still provides insight into climatic change. During the time the ice was in the north, grasses, pine, and spruce characterized the Battle Ground landscape. The spruce were most likely Engelmann spruce (Picea engelmannii), a species now more often found on drier sites at higher elevations. Needles indicate the pines were lodgepoles (Pinus contorta), also a tree of drier sites. At the opposite extreme is Orcas Island, which was completely stripped of all vegetation during the glacial period, as was the rest of the ice- covered region.

Spruce, either P. engelmannii or Sitka (P. sitchensis), mountain hemlock (Tsuga mertensiana), red alder (Alnus rubra), and pine (lodgepole and ponderosa (Pinus ponderosa) moved into parkland or open forest around Battle Ground as the Puget lobe began to retreat. Pines were also one of the dominant, early- post-glacier plants on Orcas Island, where the climate was cool and dry. The mean July temperature was 57 degrees (modern average range in Seattle is 54 to 72 degrees) and annual rainfall was less than 8 inches (modern average in Seattle is 34 inches). Around Lake Washington was a similar environment of pine, spruce, and mountain hemlock, along with grasses.

Pine remained an abundant species at Lake Washington until about 11,000 years ago, though the percentage of pine, as well as spruce and mountain hemlock, declined at Orcas Island. This was a period known as the Younger Dryas (12,900 to 11,500 years ago) and was cooler than at present. To the south, the habitat was more open and savannah-like. Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) and Garry oaks (Quercus garryana) were common, with meadows of camas (Camassia quamash) and bracken fern (Pteridium sp.).

For the next few thousand years, the climate was drier and warmer than at present, with widespread, open, prairie-like ecosystems. One unusual plant that grew as far north as Orcas was chinquapin (Chrysolepis chrysophylla), a fire-adapted, evergreen, broadleaf tree now rare north of the Columbia River. Orcas also saw the further decline of pine, as well as spruce and mountain hemlock, and an increase in oaks, which were very prevalent on the island from 7,800 to 6,000 years ago. Around Lake Washington, pollen counts indicate an open forest of Douglas fir (more prominent than at present), red alder (in riparian settings and possibly as a successional species), and bracken fern (as ground cover in forest clearings).

Changing Flora

Beginning about 7,000 years ago, the climate started to become wetter and cooler. At Lake Washington, western red cedar (Thuja plicata) showed a sharp increase, with a decrease of alder and to some extent of Douglas fir, which is more or less the modern plant community. In somewhat of a contrast, Douglas fir became the dominant conifer on Orcas Island around 6,000 years ago; it is still dominant today, in a rain-shadow-influenced environment that is warmer and drier than that to the south. Over the last 1,750 years, Orcas has become wetter, with an increase in pine, fir, and spruce, though not necessarily at the expense of Douglas fir. To the south at Battle Ground, western red cedar began to be more abundant, occupying riparian and poorly drained habitat along with red alder. At the same time, oak declined, and by about 4,500 years ago the community looked more or less like the modern one, dominated by Douglas fir, red alder, and western red cedar.

Throughout most of the post-glacial time, people have lived in the Puget lowland. The most detailed evidence of human habitation (including more than 1,000 stone flakes, hammerstones, scrapers, and projectile points) comes from a site in Redmond, where the artifacts date to 12,000 years ago. On Orcas, the remains of a bison dated as 14,000 years old has signs that indicate butchering and possible impact blows by humans, though there is some debate about the human connection.

Other archaeological sites in the Puget lowlands show that Native people did alter the environment, but the changes they wrought were dwarfed by those made by European settlers. The main tool of change used by Native people was fire, which they used to keep open the prairies found in drier part of the sound country. They did this to prevent the encroachment of Douglas fir on the habitat of oak and camas, both important food sources. Native people also burned small forest remnants to create open areas good for hunting and the growth of berries.