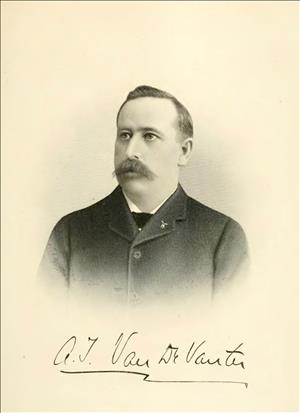

Aaron T. Van de Vanter came to King County from Indiana in January 1885, age 26. Within five years of his arrival, he helped establish the city of Kent and served as its first mayor. He was deeply involved in Republican politics and would hold political offices over the years, including two terms as King County's sheriff and two in the state Senate. An astute businessman, Van de Vanter accumulated a wide range of holdings, interests, and influence, but breeding and racing thoroughbred horses was his passion. He was the moving force behind the 1902 creation of The Meadows racetrack south of Seattle. After surviving a serious illness in 1905, Van de Vanter was badly injured in a motor-vehicle accident while on the way to the last race day of The Meadows 1907 season. Still weakened by his earlier illness, he died at home on the evening of the next day.

One Name, Many Spellings

Tracing the lineage of Aaron T. Van de Vanter is difficult. Different generations of his family (and some within the same generation) spelled their last name in different ways – Van Deventer, Vandevender, Vandevanter, and other variations. This much seems clear. Aaron Van de Vanter was born on a farm near Hillsdale, Michigan, on February 25, 1859. His paternal forebears emigrated from Holland to America before the Revolutionary War and engaged mostly in farming. His paternal great-grandfather, Peter (1742-1820), who spelled his last name Vandeventer, appeared in the first census of Huntington County, Pennsylvania, in 1790. He and his wife, Margaret (nee Miller) Vandeventer (1745-1826), had either seven or 11 children, depending on the source.

One of those children was Jacob VanDevanter (1787-1840), who adopted a different spelling. He devoted his life to farming and civic involvement. A pioneer in Indiana in what was then called the Northwest Territory, he moved there in 1831 (one source says 1821) and was a member of Lagrange County's first board of commissioners. He and his wife, Lydia (nee Fee) VanDevanter (1788-1845), had seven children, one of whom would become Aaron T. Van de Vanter's father.

This was John Fee Van de Vanter (1819-1908), born in Delaware County, Ohio. After graduating from a branch of the University of Michigan, he taught school for two or three years before returning to farming. Upon the death of his father in 1840 he purchased the interests of the other heirs to the family's 400-acre farm in English Prairie, Indiana. Two years later he married Elizabeth (nee Thompson) Van de Vanter (d. 1898) in Lagrange. According to most sources, they had three sons, including Aaron Van de Vanter, and one daughter, Elizabeth.

John Van de Vanter carried on the civic involvement that his father had practiced. His vigorous advocacy for the abolition of slavery led to a role in the creation of the Republican Party in 1854. He was an ally to and shared speaking platforms with famed abolitionists Charles Sumner (1811-1874) and William Lloyd Garrison (1805-1879). He also served in the Indiana legislature before relocating to Michigan in 1857 (again to farm), and was a delegate to the convention that nominated Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) for president in 1860. Van de Vanter would live in Michigan for the next 30 years, serving as a justice of the peace and as state superintendent of the poor.

In 1887 he and his wife moved to the Pacific Northwest, where two of their sons, Edward (1854-1938) and Aaron, and daughter Lizzie Watson were living. They settled on a farm in the White River Valley, but two years later retired from active farming and moved to a home in Kent in south King County. When Elizabeth died in 1898, John moved in with his son Aaron. As will be seen, Aaron met an untimely death in 1907, and John then moved to Chicago, where his son William lived. He died there in 1908.

Aaron T. Van de Vanter

Little is known of Aaron Van de Vanter's childhood other than that he spent it on his father's farm in Michigan and attended the public schools there. In 1882 he moved to Lagrange, Indiana, where his grandfather Jacob had pioneered, and tried his hand at a commercial enterprise for the first time, at age 23. He and a partner named Carl Berger opened an agricultural-implements business, but it was an unhappy experience. The business failed in 1884, leaving Van de Vanter almost penniless and in debt.

Van de Vanter began looking for other opportunities. From his older brother, Edward, a graduate of the Atlanta Medical College who had moved to the White River Valley in 1883 or 1884, he learned of the boom in hop farming in the Northwest, particularly in and around Kent, Auburn, and the Puyallup Valley. Pioneer Ezra Meeker (1830-1928) had planted the region's first commercial crop in the spring of 1865, to be followed by many others. Many if not most of the hop pickers were Native Americans.The British hop crop failed in 1882 and the price of Northwest hops soared. Seizing the opportunity, Van de Vanter arrived in King County in January 1885 and bought a farm on credit in the White River Valley on which to grow hops. He did well, and in 1889 purchased a second farm near Kent.

A plague of hop lice in 1892 pretty much destroyed the local industry, but Van de Vanter had diversified. He became the largest exporter on Puget Sound of another valuable crop, asparagus, and eventually owned a dairy business with 100 head of well-producing cattle. He was also active in property development, buying and platting land on Kent's Knob Hill (now known as Scenic Hill), which still has a Van de Vanter Avenue. He later became a partner with James F. McElroy in purchasing and subdividing 300 acres into five-acre tracts at Black River Junction, and later, among several other enterprises, became co-owner of Seattle's Tourist Hotel.

Politics, Never Easy

A lifelong Republican, Aaron Van de Vanter would carry the family legacy of civic involvement farther than his forebears. In 1889, after just four years in King County, he ran for a seat in the state House of Representatives but placed third. He was the president of the Washington Central Improvement Company, which laid out the town of Kent. On May 28, 1890, it became the first city in the county other than Seattle to incorporate, and Van de Vanter was elected its first mayor. On June 24, 1890, he married Martha May Triplett. They would have no children. He served a single year as mayor before being elected in 1891 as state senator for District 24, and in 1893 he served on the Kent town council while also holding his senate seat.

In 1894, with the nation reeling from the financial meltdown following the Panic of 1893, Van de Vanter put his name forward as the Republican candidate for King County sheriff. It was during this election that his business failure of a decade earlier was weaponized by a newspaper, The Seattle Weekly Telegraph, which on October 30 accused him of fleeing to the Northwest to avoid his indebtedness and characterized him as "a fugitive from justice" ("A Blundering Lie"). The strongly Republican Seattle Post-Intelligencer came to his defense the next day in a sprawling report that included a rebuttal by Van de Vanter himself and supporting affidavits by several people familiar with the facts. It established that Van de Vanter had been steadily paying off the debts incurred by the former business, even those that were legally time-barred. Some affiants claimed that his former partner, Berger, disabled by drink and chronically absent, was largely at fault for the failure but had done nothing to help repay the resulting debts.

The calumny did not end there. The local Democratic Central Committee, on the day before the November 6 election, circulated a flyer with charges based on a telegram solicited by the Weekly Telegraph from Berger. Among other things, Berger accused Van de Vanter of robbing him, and claimed that "he ruined my wife, and broke up my home. He also, to my personal knowledge, ruined several young girls at LaGrange, Ind. He is a traitor to all principles of manhood. I know him to be a thief" ("The Limit Reached").

This time Van de Vanter turned to the courts, and on November 6 the chairman and secretary of King County's Democratic Central Committee, who had spread Berger's accusations, were arrested on charges of criminal libel. In the vote that same day, Van de Vander was narrowly elected. A recount showed that he had defeated his main rival, Populist William H. Moyer, by only seven votes out of nearly 9,000 cast. The result withstood a post-election legal challenge that was eventually decided by the state supreme court, which on July 24, 1895, unanimously affirmed Van de Vanter's election as sheriff.

Van de Vanter lost his reelection bid in 1896, a loss made more painful in December that year when a fire destroyed his Kent mansion and all its contents, and serious floods severely damaged his farmland. But he was nothing if not resilient. He came back to be elected county sheriff again in in 1898. In 1902, having moved to Seattle, he was again elected to the state senate, serving in 1903 and 1905 (the legislature at that time met only every two years).

Van de Vanter joined several fraternal and social organizations in his early years in King County, including the Odd Fellows, United Workmen, Knights of Pythias, Woodmen of the World, and was a life member of Seattle Lodge No. 92 of the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks. He was also a Knight Templar in the Masons and a member of the Afifi Temple of the Mystic Shrine in Tacoma. Through both his political service and his associations, Van de Vanter "was known all over the State of Washington as a politician and pioneer of King County, and a man who figured in every important political contest in the state convention or Legislature for fifteen years or more" ("Van De Vander Is Dead …").

A Passion for the Ponies

The record is silent as to whether Aaron Van de Vanter, before moving to the Northwest, had anything more than a normal farm boy's regard for horses. What is known is that after he established roots in the Kent Valley in the mid-1880s, he began raising racehorses. In 1891, he and several like-minded friends formed the King County Fair and Agricultural Association. There had been an annual King County Fair since 1863, and it is unclear what relationship, if any, Van de Vanter's group had with it. The association's only recorded activity was to build a horse-racing track on a piece of property Van de Vanter owned in Kent. Two tracks, actually. One track was a half-mile traditional oval, for Thoroughbred racing. There was also a one-mile "kite track" that looked like a misshaped figure 8 and was used primarily for harness racing. The first track of this type had been opened in Kankakee County in Illinois the previous year and spread from there. The design featured long straightaways that led to faster times, but proved to be a short-lived phenomenon.

Van de Vanter's investment group had problems from the start, and the tracks lasted just two years. An early handicap was the failure of some of his associates to pony up their investment money. Financially weakened and able to run only short meets with low attendance, the track (which apparently had no formal name) was finally done in by the Panic of 1863 -- one of the very few Van de Vanter ventures that was not a success. The track was left in place with hopes of reopening when the economy improved, but it never would, at least in part because of damage caused by repeated flooding.

Aaron Van de Vanter was not done with the horses, and while biding his time his stable produced some impressive thoroughbreds. One biography noted: "He has always been a lover of fine horses and has bred some very valuable ones. He owns the stallion Erect, a full brother of Direct, bred by the stallion Monroe Salisbury. He also has the stallion Pathmark … This horse has been on the road for three years and has taken many prizes" (A Volume of Memoirs …).

The Panic of 1893 was a prolonged financial disaster that would only be exceeded by the Great Depression that started in the late 1920s. But on July 17, 1897, Seattle and King County got a jump on recovery over the rest of the country when the steamship Portland arrived at the city's waterfront from Alaska with more than a ton of gold from the Klondike Gold Rush. It was a timely windfall that launched the region on what would be more than a decade of prosperity. Van de Vanter and other business people of his talents thrived, and by the turn of the twentieth century he was planning to get back to racing horses on his own track.

A Stalking Horse

"Stalking horse: something used to mask a purpose" (Merriam Webster Dictionary)

Well more than a century later (2023), it is difficult to judge the motivation of the founders of the King County Fair Association, but subsequent events strongly support the conclusion that the primary and perhaps only goal of the enterprise was to build and operate a horse-racing track.

On April 16, 1901, articles of incorporation were filed with the King County Auditor's office for the "Seattle Fair Association" ("To Hold County Fair …"). Whether the name was a misprint or simply thought better of, by the time the idea was endorsed by the Seattle Chamber of Commerce six weeks later it had been changed to the "King County Fair Association" ("Fair Project Is Indorsed").

This was a profit-making enterprise, with shares held by the initial investors and members of the public One early investor was whiskey wholesaler Meyer Gottstein (1847-1917), father of Joseph Gottstein (1891-1971), later an owner of Seattle's longest-serving racetrack, Longacres (1933-1992). The articles stated that it would have capital stock of $100,000 and that 10 acres less than five miles from Seattle's then southern boundary had been purchased. The site was originally a farm owned by Seattle pioneer Charles C. Terry (1828-1867) and today (2023) is part of Boeing Field.

The stated objects of the association were described in the articles: "To develop the stock, dairy and farm interests of Western Washington; to promote good road and encourage driving thereon; to encourage the general improvement of streets, street railways and farm roads in King County." Exhibition halls were promised for all sort of exhibits – beef and dairy cattle, horses, sheep, swine, poultry, fish (canned, smoked, and pickled), machinery, cream, butter, condensed milk, all vegetables and fruit, minerals from British Columbia and Alaska, even an art gallery. All that was said about horse racing was a passing reference to "an exhibition racetrack one mile in length" ("To Hold County Fair …").

Several titans of the Seattle business community invested and were on the association's board, but it was clear from the start that Aaron Van de Vanter was first among equals. He was the secretary of the association and the manager of the fair, and he was determined to not repeat the mistakes of a decade earlier. He kept his hands firmly on the reins and made sure that those who had pledged support would honor those pledges. So unquestioned was his control that he was allowed to build a large country residence on the fairgrounds.

From the start, and despite the elaborate exhibitions described in the articles, the association was focused on the racetrack, and that was where the start-up money was spent. On June 4, 1901, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer reported:

"Work on the new fair grounds and race track of the King County Fair Association will be started within ten days on its property five miles south of the city. The association held its election of officers last week and is preparing to raise the remainder of the money needed for the construction of exposition buildings through committees which will be at work this week" ("Getting Ready for Fair").

By early in 1902, the intentions of the King County Fair Association had become much more clear. While still claiming to be raising funds for exhibition buildings, progress was being made only on a racetrack that the Post-Intelligencer characterized in a headline as "Fit for a Croesus," a reference to a king from ancient Asia Minor renowned for his wealth. Van de Vanter's King County Fair Association would never hold a King County Fair at The Meadows. Even so, the local newspapers seemed supportive of the plans for the first several years, but soured on the sport when a number of scandals were later exposed. One of the first and most vociferous critics of The Meadows and sports betting was The Seattle Star.

Difficult Years

The history of The Meadows has been well-reported elsewhere, most comprehensively in Greg Spadoni's two-part account referenced in the sources below. The track thrived for several years, running both Thoroughbred and some harness races, but a number of scandals in its later years and the anti-gambling crusade of the state's Progressive Movement led the legislature, in 1909, to ban betting on horse races.

Aaron Van de Vanter did not live to see the end of the racetrack that was largely his creation. In 1905 he had been struck by what The Seattle Times characterized as "a sickness which embraced peritonitis, brain fever and typhoid" ("Van de Vanter Is Dead …"). It was a three-month siege, with a partial recovery, then a relapse. On February 18, 1905, The Seattle Star reported "Senator A. T. Van de Vanter's condition today is very much worse, and at the time The Star goes to press very little hope is entertained for his recovery" ("Very Low").

It was a see-saw battle, closely watched. A headline in The Star on March 13 read "Van de Vanter Is Better," but four days later the paper reported that "his physician has no hope of his recovery. It was announced this afternoon that he could not live many hours" ("Van de Vanter Worse"). Somehow he pulled through, barely, and although left in a weakened state he soon was carrying on with his many business and political interests.

Well more than two years later, on September 14, 1907, Van de Vanter was riding in an open car near Georgetown with three friends and a chauffer, heading to The Meadows. At Lander Street the driver attempted to pass between two interurban streetcars on adjacent tracks, one northbound and one southbound According to an eyewitness who was riding in the southbound car, "the chauffer attempted to cross the tracks in front of (the southbound) car. A northbound car on the opposite track passed at the same time and the automobile was caught between the two coaches and demolished" ("FATAL AUTO ACCIDENT!").

That headline was a little premature, but all the occupants were injured, and Van de Vanter "was thrown, as from a catapult, from the automobile 15 fifteen feet to a pile of debris" ("Van de Vanter Is Dead …"). Nonetheless, it appeared at first that the worst injuries were sustained by Lincoln Davis (1862-1917), a state senator and longtime business partner of Van de Vanter, and another passenger. They were taken to hospital, while Van de Vanter, thought to be less seriously hurt, was taken to his home. Once there, he was tended to by Dr. F. M. Carroll (1870-1958), who had saved his life two years earlier.

On the day of the accident, bedridden at home, Van de Vanter told his closest friend, Julius Redelsheimer (1852-1914), "If I'm not injured internally, I'll pull through. I'm good for another fight" ("Van de Vanter Is Dead …"). But his doctor knew there were internal injuries, and that Van de Vanter would not survive. He share this with Mrs. Van de Vanter, but not with his patient.

The moment of his death, 9:42 p.m. on September 15, was described in The Seattle Times:

"Two broken ribs caused intense pain and difficulty in breathing. The jar caused by the fall developed peritonitis. His heart, which held him on an even keel through countless political battles, which had made him believe that nothing was too difficult for him to undertake, either in political warfare of the most savage kind, in horse racing or in business, finally tired of the struggle. It did not give even his physician, Dr. Carroll, notice of what was coming. It did not hesitate or slacken in its pulsation.

"With the sick man's eye as clear as ever and his mind perfectly conscious of all around him, the heart stopped beating without warning. He gasped just once and was dead" ("Van de Vanter Is Dead …").

The report went on, "… he had lost his ambitious strength through his illness. There was something missing that the physician could not locate … [The] old willpower that held him up and made him a powerful factor in politics and business was gone" ("Van de Vanter Is Dead …").

Van de Vanter left to his wife an estate valued at about $250,000, the equivalent of more than $8 million in 2023 dollars. Had he not been in the accident, it was likely that he would have attained the longevity enjoyed by his father John and brother Edward. It was revealed after his death that, at the urging of his wife, he had agreed to take six months, and perhaps a year, off from all of his business and political entanglements to travel and recover fully from his 1905 illness. To start, the Van de Vanters were going to take the train to California with Julius Redelsheimer and his wife for an extended stay.

But Van de Vander insisted on one concession. He would not leave until he had seen the 1907 racing season to its end. It was while he was on his way to the last racing day of the year that Aaron Van de Vanter sustained the injuries that would kill him, a tragic irony that seems to have escaped mention in the local press.