From 1931 through 1935, Seattle was terrorized by its first serial arsonist, and during that time more than 150 of the city's warehouses, factories, and buildings were destroyed by fire. Set amid the backdrop of the Great Depression, this non-stop series of arsons became an exhausting nightmare for the Seattle Fire Department during which it would often respond to one fire when an alarm would be sounded for another. Top investigators were assigned to the case, though no amount of police work seemed to turn up any solid leads, putting the entire city on edge. There would be a high-profile arrest, but not before some of Seattle's most prized landmarks were destroyed by an unfettered pyromaniac who tormented locals for four long years.

The Firebug Strikes

On the evening of March 19, 1931, a fire broke out inside a three-story building occupied by the Art Woodworking Company, near what is now T-Mobile Park. A total of 15 fire companies responded to the scene and valiantly fought the three-alarm blaze for several hours. Their efforts proved to be futile, as the wood building was packed full of flammable varnish and paint. Described as a "spectacular fire of undetermined origin" ("Blaze Menaces …"), it would prove to be the first confirmed target of an anonymous arsonist who would later be dubbed the "Seattle Firebug."

A month later, on April 14, 1931, nine different fire stations would find themselves urgently responding to an early-morning alarm at the Luna Park Natatorium. Described as a "swimming palace," the West Seattle landmark was the last remaining structure from the famous Luna Park amusement park. The building, which stood on a broad wooden pier, featured two heated pools and was one of the city's most popular attractions. The fire alarm at the natatorium was sounded at 3:46 a.m., and within an hour the blaze could be seen from the other side of Elliott Bay. Many watched the historic fire from Queen Anne and Beacon Hill. In addition to the battalion of firetrucks, two fire boats were deployed to help douse the flames. Despite the large-scale response, the building – including the pier it was housed on – was completely destroyed. The structure would be declared a total loss, and after rebuilding costs were deemed too expensive, the city would condemn the property in 1933.

Over the next several months, many other buildings met the same fiery fate, including factories, docks, warehouses, lumber yards, and railroad boxcars. One of the more notable of these fires took place on June 9, 1931, when a blaze swept through several south-end industrial plants on the waterfront, destroying the Albers Flour Mill (which made the city's favorite brand of pancake mix), Puget Sound Machinery, and the Carman Furniture Manufacturing Company. The bright flames could be seen for miles, and "the reddened sky and the scream of engines brought hundreds of spectators" ("Industrial Tract Razed …").

It became apparent to most residents what investigators already knew – Seattle was dealing with a dangerous arsonist. Seattle Fire Marshal Robert L. Laing (1891-1958) was assigned the task of capturing the person responsible. Laing had been a Seattle firefighter since 1914 and had quickly risen through the ranks, becoming a commissioned fire marshal in 1923, the youngest fire marshal in the country. By the 1930s, Laing had earned a reputation as a seasoned sleuth and was described by colleagues as "a shrewd investigator of fires" ("Gets Medal"). He had a track record for hunting down and prosecuting arsonists, but this case would prove to be one of the most difficult of his career.

On January 22, 1932, the Reliance Iron Works building in the Georgetown neighborhood was destroyed by a late-night fire. By spring of that year, the fires had started to become almost a nightly occurrence, with the Blackstock Lumber Company, the Stewart Electric Company, and the Bayside Garage all meeting their fiery fates at the hands of this unknown firebug. These were followed by an enormous blaze on March 22 in which an entire city block of buildings, including Washington Iron Works, was gutted by fire. It was one of the largest fires in Seattle history, second only to the Great Seattle Fire of 1889. As The Seattle Star described the frightening situation, "Night after night, the sky was lighted by the orange tongues of flame. Clouds of billowing smoke marked each new destruction, and in the industrial district the charred walls of the buildings were a grim record book of the mounting fires" ("'Burning Genius' Sets …").

Fire inspector Laing – who had been at every one of these fires – determined that they were all the work of one arsonist, and he began working with a group of Seattle police detectives in a concerted effort to capture the person responsible. Special police units aggressively patrolled the streets, and watchmen were secretly stationed throughout the city. Anyone looking suspicious or caught walking alone at night was stopped and asked to explain their business. Hundreds of people were questioned, but to no avail.

The Burning of Dugdale Park

Despite the constant threat of fire, local residents attempted to lead as normal lives as possible. This included the cherished pastime of baseball. On July 4, 1932, a packed house at Dugdale Park watched the Seattle Indians play a doubleheader, followed by a traditional Independence Day fireworks show. Dugdale Park – the first double-decked baseball stadium on the West Coast – was named after its builder, Daniel E. Dugdale (1864-1934), the so-called "father of Seattle baseball." Both Babe Ruth and Ty Cobb had played at Dugdale, and it was considered by many to be one of the finest ballparks in the West. Shortly after midnight, when the 15,000-seat stadium was empty of fans and all gates had been securely locked, urgent calls started pouring in that the 19-year-old ballpark was on fire.

The first responders found much of the grandstands already engulfed in flames, and the blaze was immediately declared a three-alarm fire. It was a colossal firefighting effort, made especially difficult by a brisk wind that blew across the playing field, fanning the flames and sending hot embers up into the air. Hundreds of nearby residents, alerted by the inferno's massive glow and the continuous wail of sirens, packed into nearby streets to watch the incineration of their beloved ballpark. By sunrise, all that remained was a charred tower of outdoor lighting that was somehow still in working order. The rest of the park had burned into a smoldering pile of rubble. It would later be described as one of the most spectacular blazes in the city's history. Initially, the previous night's fireworks show was thought to be the likely culprit. It would not be until three years later, in a police interrogation room, that a late-night confession would reveal that it was another act of arson.

The Fires Continue

More fires followed the devastating loss of the ballpark, including the Puget Sound Machinery Shop, Pacific Waste Paper, and Interbay School. On October 7, 1932, a fire was reported at the A. F. Ghiglione and Sons macaroni factory after nearby South Seattle residents saw a red glow emanating from the three-story building. More than 125 firemen from several different battalions battled the blaze for hours, but were handicapped by a dense fog and ultimately unable to save the plant. At this point, fire investigators were tight-lipped about the ongoing fires, but Frank Ghiglione – the president of the company – acknowledged that "the fire was started by an incendiarist" ("Macaroni Plant …").

Throughout most of 1933, the number of fires considerably slowed, leading some to speculate that the arsonist may have moved on. Such speculation ended on October 1, 1933, when several businesses were burned in a single night, including the Georgetown Presbyterian Church, the Miller Lumber Company, and the White River Lumber Company. A week later, the Marine Products Company, City Deck, and Smarts Auto Freight Company were destroyed by fire. Investigators confirmed that the methods used in this batch of fires matched all the previous ones.

The arsons continued well into the summer of 1934, with the Globe Feed Mill being lost to fire on July 1, followed by the Ehrlich-Harrison Lumber Yard and the Brace Lumber Company. Soon after, the fires suddenly stopped. Days of no arsons turned into weeks, which then turned into several months. Officials grew cautiously optimistic that the firebug had left town. All special patrols were slowly withdrawn from the streets.

Six months later, starting in January 1935, the fires suddenly returned. Inspectors immediately knew it was their guy, and the previous investigation resumed where it had left off. Things took a curious turn on February 11, 1935, when a small fleet of fire engines responded to yet another alarm. Expecting to find a blazing fire, they were somewhat relieved to discover that it had been a false alarm. However, a hand-written note had been attached to the alarm box, intentionally left for the firemen to discover. It read in part:

"LOOK OUT! So long as I am blackballed for not being in the last war I will continue many fires in industrial plants. FIREBUG ALL OVER COAST."

Other notes soon followed, some of which contained racist language and identified the author as being a "white citizen." The first world war was once again referenced:

"You blackballed me since

1917 war–wrongfully.

Give me decent living

Or I fire big" ("Fire Department Central Files").

At first glance, the grammar and handwriting appeared to be rather crude and from someone with a low level of education. Right away, though, Inspector Laing suspected subterfuge. He consulted with a local detective – a handwriting expert – who examined the letter and affirmed Laing's theory. Much of the writing was cramped and unnatural looking, but some of the letters were nicely formed, as though the person had accidentally revealed their true writing in certain parts. "It's a disguise," the detective told Laing, "You're dealing with a smart man. I would guess that the man who wrote this was a bookkeeper or stenographer at one point" ("The 'Burning Genius' Returns").

On April 17, 1935, two major fires took place on the same night: the Eastlake Lumber Company and the Yeaman Brothers Mill. On April 26, the Emanuel Lutheran Church was torched, followed by the Northern Pacific Fuel Company. It once again became a nightly routine, with building after building being lost to fire. Laing dutifully attended each one of these fires, hoping to gather evidence that would finally break the case.

Captured

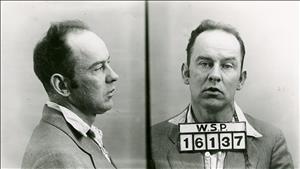

Everything would finally come to an end on the evening of May 4, 1935, when someone set fire to the Saint Spiridon Russian Orthodox Church on Lakeview Boulevard. Nearby cafe workers, alerted by the frantic barking of a dog, spotted a shadowy figure fleeing from the scene and gave chase. They managed to detain the person, who was described as dirty and unkempt. When police arrived, the suspect identified himself as Robert Bruce Driscoll (1893-1970).

Driscoll was driven to police headquarters for further questioning. At first, he was steadfast in his denial about setting any fires. After a couple of days of interrogation, though, certain biographical details began to emerge. It was revealed that he was a 43-year-old vagrant who frequented the city's breadlines and soup kitchens, and usually found shelter in abandoned railroad cars. As far as his background, he confirmed that he was college educated and had previously worked as an accountant. He certainly matched the profile, though police were still unable to obtain a confession.

When Laing finally had his turn in the interrogation room, the first thing he did was obtain a handwriting sample from Driscoll. As suspected, it closely matched the writing from the notes. When confronted about this, Driscoll eventually broke down and confessed to being the arsonist, motivated by a deep disdain for society, which he felt had failed him. As his signed confession explained, "I done this because of my destitute circumstances and because I was sore at the world in general" (Fire Department Central Files).

Other key details about his life also began emerging. He was born in Spokane in 1893 and was one of seven children. His father was a musician and played in various orchestras, which caused the family to move around quite a bit. They eventually settled in Portland, Oregon. After graduating from high school, Driscoll attended business school, where he trained to become a bookkeeper. He worked for a number of years as a stenographer for the Northern Pacific Railroad, as well as for the Tillamook Fire Department in Oregon. In 1917, when the United States entered World War I, Driscoll attempted to avoid military service by filing as a conscientious objector. However, draft officials reportedly began harassing him and tried to involuntarily enlist him. At the same time, his wife divorced him and he subsequently lost his house. He found himself indignant, bitter, and homeless. He drifted around various logging camps in Oregon and Washington before finally arriving in Seattle in 1918.

At that time, the city had been swept up in various labor protests, most of which were organized by the Industrial Workers of the World (otherwise known as The Wobblies). They were known for delivering soapbox sermons out on the streets as well as their popular newsletters. Their underlying message of a suppressed and exploited working class resonated with Driscoll. He began participating in their protests and was reportedly present during the Seattle General Strike of 1919. As he explained to detectives, "I didn't really get going on setting fires 'til I came to Seattle and heard those communists making speeches in the Skid Road. They get you all riled up. I'd go in the parades, and then, when I felt mean, I'd set a fire … I was just waking them up, to do something for us" ("The 'Burning Genius' Returns …").

At first, empty railroad cars were the targets of his fires, but he eventually graduated to small buildings. By that time, following the stock market crash in 1929, he was living with hundreds of other homeless and jobless people in the "Hooverville" shanty town that had emerged on the Seattle tide flats. He told police that he hated the "bosses and capitalists" and "wanted to show them they couldn't push me around" ("Started 90 Files"). Summarizing his bitter and resentful outlook on life, he stated, "I set the fires – sure. Plenty of them. Why did I do it? Well, I was feeling mean. I set those fires to show the industrialists that they ought to do something for me and the men like me" ("Church Firebug Admits …").

On May 28, 1935, Driscoll appeared before a King County Superior Court judge and was sentenced to 10 years at the Walla Walla State Penitentiary. Inspector Laing, who would later serve as the city's fire chief, visited Driscoll a few times at the prison, perhaps to gain some useful psychological insights into what motivated such a person. Driscoll was said to be unremorseful and promised more arsons if they ever let him out. "I'm crazy about fires," he said, "I guess if I was out tomorrow I'd start some more fires. It's better that I'm here" ("The Burning Genius …"). Driscoll was incarcerated at Walla Walla until 1941, then was transferred to Eastern State Mental Hospital until 1945, when his 10-year sentence expired. He was then involuntarily committed to the hospital, where he stayed for an unknown period of time.

After that, Driscoll dropped from sight, but he lived for many years. On September 2, 1970, he died while a resident of the Buena Vista Nursing Home in Auburn, age 78. His death certificate lists his occupations as "musician and secy" and cause of death as "Cerebro Vascular Hemorrhage" (Certficate of Death). There is no mention of his infamous past.

Driscoll's story is somewhat emblematic of Depression-era Seattle. Current estimates hold him responsible for more than 175 fires. It should be noted that while he never admitted to lighting the Luna Park Natatorium fire, he is widely considered to be the prime suspect given the time frame and the particular style of arson that was employed. Amazingly, nobody was killed or even seriously injured during his four-year arson spree.

Driscoll's rampage provides a rather interesting footnote to local sports history. After the torching of Dugdale Park in 1932, the Seattle Indians were forced to relocate to a lesser-quality field in lower Queen Anne. This new venue never worked for the Indians, especially during the height of the Great Depression. By 1937 the team was on the verge of bankruptcy and ended up being sold to local brewery magnate Emil Sick. He rebuilt Dugdale Park into a concrete and steel ballpark known as Sicks' Stadium and introduced the city to its new minor league baseball team, the Seattle Rainiers. The stadium put Seattle in position to acquire its first major-league franchise, the Seattle Pilots, later replaced by the Mariners. It has often been surmised that the trajectory and outcome of Seattle baseball history would have looked a lot different if Dugdale Park had not burned down.