On June 20, 1859, Captain (Brevet Major) Pinkney Lugenbeel (also spelled Lougenbeel) (1819-1886) arrives in the Colville Valley and selects a site near the present town of Colville, Spokane County (later Stevens), for establishing a new fort. Initially it is called Harney’s Depot, named for Brigadier General William S. Harney (1800-1889), his commanding officer, who has authorized the fort as a means of defending miners and settlers encroaching into Indian tribal areas as yet unsecured by treaty. The establishment of Fort Colville in 1859 comes on the heels of the 1858 defeat of Colonel Edward Steptoe (1816-1865) by Indians near present Rosalia and the subsequent victories of Colonel George Wright (1803-1865) in the battles of Four Lakes and Spokane Plains during the Indian War of 1858. The fort will also serve as the headquarters and provide escorts for the American contingent of the International Boundary Commission charged with locating and marking the 49th parallel as the boundary with Canada. The name of the fort soon changes to Fort Colville (not to be confused with the earlier Hudson’s Bay Company fur trade post, Fort Colvile, spelled with one “l” in the second syllable, and located 15 miles west on the Columbia River at Kettle Falls). A civilian village, Pinkney City, named for Lugenbeel, develops just across the creek to serve as a supply and trading center for the fort and surrounding countryside. Fort Colville continues under a succession of commanders until its closure in 1882.

Founding a Fort on Mill Creek

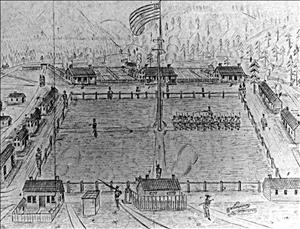

On June 1, Lugenbeel departed from Fort Walla Walla over what became known as the Colville Road or Colville Military Road to march the 210 miles north to the Colville River Valley. The site he selected for the fort was on Mill Creek, a tributary of the Colville River, three miles northeast of the present town of Colville. His orders were to build a post that would house more than 300 men. He attempted to contract with a newly built sawmill for lumber and labor to construct the buildings, but was quoted such exorbitant rates that he put in a dam on Mill Creek and built his own sawmill abut a half a mile above the fort. He was able to supply his post and then lease the mill for cutting lumber for settlers. The completed fort consisted of a hospital, three officers’ barracks, a storehouse, a guardhouse, three company kitchens, four company barracks, a bake house, a blacksmith shop, a granary, a carpentry ship, and eight laundry buildings. The buildings surrounded a large rectangular parade ground.

While some men were building the fort, others were cutting hay in the valley for company livestock. The fort grew its own vegetables and got flour from a gristmill on the Colville River. The mail was supposed to come once a week but was often delayed by severe weather, including the deep snows of several especially hard winters. Under normal circumstances, it took 10 days from Portland and 30 days from Washington, D.C. Commanders frequently complained to their superiors about the delays in pay for their men.

Throughout the history of the fort, the commanding officers kept a monthly report or “Post Returns.” These invaluable documents are housed at the National Archives and are also available on microfilm at the Colville Public Library.

An early count of enlisted soldiers showed a total of 266, with an average age of 30, only 54 of whom were born in the United States. The largest contingent by far was from Ireland, with 117. This is not surprising, as many who had fled the Irish potato famine of 1845-1849 and its aftermath found the United States military a ready source of employment. On the officers’ roster, Lugenbeel’s rank appears as Bvt. Major. The post entries always included the names of deserters. Many troops who left as they completed their time of enlistment settled in the valley. One was a Swiss immigrant, John U. Hofstetter (1829-1906), who moved first to Pinkney City and then became the “father of Colville.”

The Better-Mannered British

The British contingent of the International Boundary Commission established their headquarters near the old Hudson’s Bay Fort Colvile on the site of what would become the original town of Marcus. They were occasional guests at the U.S Fort Colville. A British officer, Lt. Samuel Anderson, describes a Christmas feast in 1860:

“The Americans at their garrison celebrated their Christmas in their usual way — one man stabbed, another shot at, several heads broken and eyes blackened, accompanied with several other incidents of a minor character, such as their military surgeon breaking his fist in some pugilistic encounter with a citizen. At dinner they have a curious fancy of heaping all kinds of miscellaneous articles on their plate at the same time and don’t seem to care for a change of plates. They all make a practice of putting their knives into their mouths, dive into the salt with their knives, for they are not aware of the existence of salt spoons ... and we had to drink sherry out of liqueur glasses!” (Graham, 14)

Civil War Years

During the summer of 1860, Lt. John Mullan (1830-1909), of Mullan Road fame, visited the fort to ascertain improvements to the Colville Military Road, which would connect with his Mullan Military Road, then under construction between Fort Benton, Montana, and Walla Walla, Washington Territory.

The Civil War brought changes to the fort. Officers who swore allegiance to the Union were transferred to Civil War duty. Southern sympathizers were discharged. The unruly 2nd California Voluntary Infantry, said to be “largely criminals from the streets of San Francisco” (Peltier, 64), replaced the enlisted Regulars of the 9th Infantry at the fort.

Lawlessness and Liquor

Because of their lawlessness, Lugenbeel’s successor, Major James Freeman Curtis (d. 1914) closed the distillery and ordered all the liquor destroyed at the fort and in Pinkney City, reporting to his superiors: “The character of the men in my command is such that life and property is not safe when they are drinking ... . The vile liquor manufactured near the military reserve needs abatement” (Graham, 21). During his command, the fort held its most notable social event, a ball on Washington’s Birthday, February 22, 1862, attended by more than 400 Indians, settlers, and members of the Boundary Commission. No alcohol was served.

The next commander, Calvin H. Rumrill (d. 1877), rescinded Curtis’s anti-liquor orders, but may have regretted it, as liquor peddled by settlers continued to increase violence in the area, with the ever-present risk of enflaming a new Indian war. He reported in 1862:

“The whole country has been drunk for the past ten days, Indians and all. It is impossible to keep liquor from the Indians when it is in the country ... . I am very much in want of horses, as parties who dispose of liquor to the Indians come within 50 or 60 miles of the post with pack animals and decamp before I can reach them on foot ... . They are a class of men who are perfectly lawless” (Graham, 22).

Washington Territorial Volunteers replaced the troublesome Californians, and they, in turn, were replaced with Oregon Volunteers. At the end of the Civil War, Fort Colville was again garrisoned with Regular troops. There were frequent changes of command, and troop numbers fluctuated over the years: For example, in 1864, there were only 65 men and four officers. In 1872, the total was only 59. By 1880, it had risen to 144. Beginning in 1872, with the establishment of the Colville Reservation, the main duty of the garrison was to move Indians onto the reservation. Cavalry was first assigned to the fort in 1875.

Church of the Immaculate Conception

Priests from the Coeur d’Alene mission visited the fort to minister to the many Irish Catholics; however, these visits were infrequent, and many soldiers and settlers wanted a church with a resident priest. With the permission of Father Joseph Joset, soldiers assisted with construction of the Church of the Immaculate Conception, a simple wooden building, over a mile south of the fort at the southeast corner of the present Calvary Cemetery.

By 1862, a priest was offering masses attended by soldiers, settlers, and Indians, as well as baptizing, marrying and burying members. Though no longer standing, the church continued to serve the community long after the fort was gone.

Last Days of the Fort

The usefulness of Fort Colville had been questioned as early as 1871, when the commanding officer, Major John Egan, notified the Territorial Legislature that it was no longer needed to protect settlers from Indians. The legislature passed a resolution to Congress to that effect, but the Army did not disband the fort until September 1882, when it was replaced by Fort Spokane, located near the confluence of the Spokane River with the Columbia. Local residents dismantled buildings at the fort and hauled them to the newly formed town of Colville, some three miles southwest, before the Army could salvage them to use at Fort Spokane. Residents also moved their own buildings and lumber from Pinkney City to Colville.

Even though the fort had been officially disbanded in 1882, a small unit remained there until 1885 to look after the cavalry horses, because there was not yet adequate hay and grain at Fort Spokane. In 1883, General William Tecumseh Sherman (1820-1891) inspected what remained of the fort during his last official inspection of forts of the West. One of the distinguished officers in his party was an engineer named George Washington Goethals (1858-1928), who would later build the Panama Canal. Interestingly, the Sherman party also included chiefs Moses and Tonasket.

Not a trace remains today of Fort Colville or Pinkney City, although the area the fort once occupied is still called Garrison Flats.