The small city of Cosmopolis on the south bank of the Chehalis River in Grays Harbor County lies on the ancestral land of the Lower Chehalis Tribe. It is the oldest city on Grays Harbor, first claimed by a white settler in 1852 and named and platted in 1861. For two decades after that there were few or no inhabitants and several small-business failures. The first lumber mill opened in 1881, and the property was purchased by milling and shipping giant Pope & Talbot in 1888. Until its closure in 1931, the Cosmopolis mill was widely infamous for low wages, poor food, and unsafe working conditions. The mill company dominated the town, and little was recorded of the details of early civic life. When the mill ran out of trees in the late 1920s it was closed, the site purchased by its longtime manager, Neil Cooney. After his death in 1943 there was a brief revival of sawmilling before the Weyerhaeuser Company bought the property in 1957 for use in pulp production. Today (2025) the pulp mill is idle, its future in doubt, and Cosmopolis is coping with the economic loss and ecological burdens that are the difficult legacy of its industrial past.

Rejected Treaty

In 1852 James Pilkington took a Donation Land Act claim on the south bank of the Chehalis River, about 4 miles east of the river's entry into Grays Harbor. His 155.5 acres had long been part of the realm of the Lower Chehalis Tribe, and in 1855 it would be the site of the Chehalis River Treaty talks. The treaty council began February 25, 1855, with Washington Territorial Governor Isaac I. Stevens (1818-1862) and his team and representatives of the Quinault, Queets, Satsop, Lower Chehalis, Upper Chehalis, Shoalwater Bay, Chinook, and Cowlitz tribes. Stevens invited James Swan (1818-1900), a multi-talented explorer, ethnographer, and author, who later wrote an account of the negotiations.

Stevens proposed that the federal government purchase all the lands occupied by the tribes, and in return, "The Indians were to be placed on a reservation between Gray's Harbor and Cape Flattery, and were to be paid for this tract of land forty thousand dollars in different installments" (Swan, 344). The tribesmen clearly did not fully understand the particulars of the proposal and Swan noted, "The difficulty was in having so many different tribes to talk to at the same time, and being obliged to use the [Chinook] Jargon, which at best is but a poor medium of conveying intelligence. The governor asked if any one of them wished to reply to him" (Swan, 345). A Chinook chief named Narkarty spoke with particular eloquence:

"We are willing to sell our land, but we do not want to go away from our homes.

"Our fathers, and mothers, and ancestors are buried there, and by them we wish to bury our dead and be buried ourselves. We wish, therefore, each to have a place on our own land where we can live, and you may have the rest; but we can't go to the north among the other tribes. We are not friends, and if we went together we should fight, and soon we would all be killed" (Swan, 345).

Swan reported, "This same idea was expressed by all, and repeated every day" (Swan, 345). In the end, the tribes refused to sign the treaty, marking the first failure in Stevens's campaign to dispossess the territory's indigenous people of their land.

City of the World

Pilkington had built a small cabin in a clearing near a Lower Chehalis village, but his relations with the tribe were always fraught and deteriorated after the treaty talks failed. Matters became worse when Pilkington was rumored to have "shot and killed a Grand Mound Indian over an Upper Chehalis Indian maiden" (The River Pioneers, 100). In 1858 he sold his claim for $1,500 to David F. Byles (1833-1897) and Austin E. Young (1830-1909), who had come west from Kentucky in 1853. At the time, the property was located in Chehalis County, which had been created from part of Thurston County in 1854. In 1915 the legislature changed its name to Grays Harbor County, largely to avoid the confusion caused by the city of Chehalis being the county seat of nearby Lewis County.

On June 25, 1861, Byles and Young recorded the first plat of a proposed town, dedicating the property to the public "in consideration that a town to be called Cosmopolis is to be laid out on our lands …" (The River Pioneers, 101). One account of the origin of the aspirational name came from John Roger James (1839-1921), an early settler in Grand Mound:

"I remember a little Frenchman named Brun came to our house with pack-horses loaded with provisions and utensils for farming and had two little pigs lashed by their feet, balanced across the horse's back like saddle bags. He was on his way to Grays Harbor. The next morning as we were eating salmon for breakfast, Mr. Brun asked Father: 'What is that name that means the city of the whole world?' 'That is Cosmo, the world, and Polis, city,' Father said. 'Ah, yes, that is it,' Mr. Brun cried, 'Cosmopolis, the City of the whole world. That is to be the name of my townsite on Grays Harbor'" (Told by the Pioneers, 85).

Thirty Years of Failure

Brun quickly disappeared from history. Byles and Young started a brickyard at the Cosmopolis site, which was not successful. The Lower Chehalis still resented the settler presence, and two years after platting Cosmopolis the Byleses and Youngs were ready to leave. The property was taken over by David Byles's cousin, George W. Byles, and George Lee, tanners from Tumwater, but still owned by David Byles and Austin Young and their spouses. The new occupants put up a building and fashioned huge tanning tanks, but they had overestimated the hide supply and underestimated the distance to possible markets. "Their efforts lasted hardly more than two years, and succeeded mostly in giving Cosmopolis the name 'Stinkopolis'" (The River Pioneers, 264). After the two abandoned the site, it seems to have sat vacant for several years.

Reuel Nims (1839-1911) eventually purchased the Byles and Young interests but had no better luck. A merchant, he converted the remains of the tannery building into a warehouse for his inventory, which included a large quantity of lime. The Chehalis is a tidal river at Cosmopolis, and an unusually high tide flooded the warehouse and started a fire when the water hit the lime. The building burned to the ground, and yet another settler had failed at the City of the World.

Next up was Charles Stevens from Humptulips. His plan was to build a grist mill on the site of the tannery. Some sources say he had no experience grinding grain, others that he had been a successful miller "down south" (They Tried to Cut It All, 42). If so, his success was not to be repeated at Cosmopolis.

Stevens bought the Cosmopolis site from Nims in 1877 and built a two-story grist mill and a flume from Beaver Creek (now known as Mill Creek) to the mill. His plan was to ship harvested wheat from upriver, mill it, then ship the finished flour back upstream to be sold. However, by the time the wheat reached the mill it was wet and could not be ground into "passable flour" (The River Pioneers, 265). Stevens gave up the milling operation in 1879.

Eighteen years had passed since the Byles and Austin families platted Cosmopolis. At least four businesses had failed there, and the only permanent dwelling on the property was Pilkington's original cabin. But Cosmopolis was about to meet its destiny, and it came first in the form of Jason C. Fry (1832-1889).

First Cut

Jason Fry was the first of four brothers who came West after the death of their parents. His brother John arrived in 1852 and the two started logging Jason's claim at Coffin Rock in Oregon. After almost his entire stock of cattle and horses died in a harsh winter, Jason was hired to teach farming and blacksmithing on the Quinault Indian Reservation. In 1879 he learned of Stevens's problems and convinced him that his flume could be better used to power a sawmill. His brother John, a skilled metalworker, came to Cosmopolis to help set up the mill.

After some difficulty raising money, the heavily mortgaged mill cut its first lumber in 1881. Other investors bought out the interests of Stevens, "a cranky old man with ideas of his own" (They Tried To Cut It All, 43). Some of the mill's early output was used to build the first three houses in Cosmopolis (not counting Pilkington's original cabin). Shortly after that,

"Jason and John Fry … devised the first lumber cargo to leave Grays Harbor. True, it was but a small parcel of cedar in the little schooner Kate and Ann, but it was the forerunner of thousands of cargoes to depart for worldwide ports thereafter … the greatest procession of lumber-laden ships the West Coast ever was to know" (The River Pioneers, 127).

The mill was a profitable operation for the next three years. In 1884 it cleared $3,000 and sold enough lumber to finance a steam-powered mill on the site. Jason Fry moved on to become a preacher, but died of appendicitis in 1889.

Rapid Growth

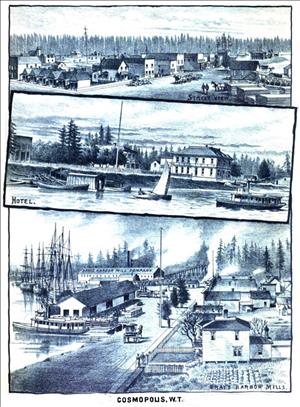

Cosmopolis began to grow in the early 1880s. Forty acres of the site were cleared in 1883 and, although still sparsely peopled, the beginnings of a real town appeared, with homes, stores, even a hotel. The success of the new steam-powered mill soon drew out-of-state interest, and in 1887 W. H. Perry of the Perry Lumber & Mill Company of Los Angeles bought it. Pope & Talbot, a pioneering lumber and shipping firm from San Francisco, which in 1853 had established at Port Gamble the first lumber-industry company town in Washington Territory, also wanted in on the potential of Grays Harbor.

The Pacific Pine Lumber Company of San Francisco, a consortium of 11 mill companies dominated by Pope & Talbot, tried to buy Perry's interests in Cosmopolis, but he refused to sell. In retaliation, Pope & Talbot bought a quarter section of land near the town and planned a competing sawmill. Perry capitulated, selling out to the consortium in July 1888 for $135,000. Plans to build a new mill were abandoned, and soon the other shareholders of the Pacific Pine Lumber Company withdrew, leaving Pope & Talbot in full ownership and control.

In May 1892 a Northern Pacific Railroad train backed over a new steel bridge connecting Junction City on the north shore of the Chehalis River to Cosmopolis on the south. The railroad gave Cosmopolis a land link to the deepwater port of Tacoma just 60 miles to the north and to the lumber-poor Midwest, and it was greeted by the town's 450 inhabitants and a 20-piece band. Chester F. White (1852-1917) became the second manager of the Cosmopolis mill in 1892 and soon established a tank and box factory on the site. According to Pope & Talbot's company history:

"[White] foresaw that the agricultural development of the Pacific Northwest would create a large demand for water tanks on farms. These were made of Douglas fir, but spruce went into the boxes manufactured at Cosmopolis. Since it did not impart a taste to the produce shipped in such containers, it was ideal for this use. The box factory alone used 150,000 feet of lumber a day" (Coman and Gibbs, 219).

The name of the mill was changed to the Grays Harbor Commercial Company (GHCC) in 1895. Soon it was operating two shifts a day, and at its peak employed 1,200 men. Planing mills, drying kilns, and two shingle mills were added. "By 1900, Cosmopolis was producing more lumber than any other sawmill on Grays Harbor. Its cut was more than 39 million feet in the year 1900, and approximately 33 million feet were shipped by rail" (Conan and Gibbs, 219).

A Company Town?

The Grays Harbor Commercial Company had an insular, go-it-alone attitude, as one history describes:

"Expansion became the order of the day at Cosmopolis. But unlike Aberdeen, Hoquiam, and Montesano – who offered investors liberal inducements of land and credit, encouraging competition – Pope & Talbot did not offer any sort of advantages to manufacturers. They were not interested in sharing their business interests in Cosmopolis where they owned everything – stores, messhouses, bunkhouses. Competition was neither encouraged nor allowed" (Weinstein, 21).

Although several sources identify Cosmopolis as a "company town," it is unlikely that the company "owned everything." The town was incorporated under state law in 1891 based on a unanimous vote by 34 male citizens of voting age. George Stetson, the first manager for Pope & Talbot's Cosmopolis operations, was elected the first mayor, but did not vote on incorporation. Pope & Talbot would have had little reason to initiate or even support the 1891 incorporation, simply because there would be no conceivable benefit to the company. On balance, it seems more accurate to characterize Cosmopolis as company-dominated rather than company-owned.

Despite the horrible reputation the mill was to earn, Cosmopolis outside the mill property seemed typical of other young communities. There were, eventually, schools, a city hall, library, fire station, jail, rooming houses, churches, a bowling alley and cigar store, baseball teams, a Northern Pacific depot, and other amenities of small-town life.

Enter Neil Cooney

Neil Cooney (1860-1943), a native of Canada's remote Prince Edward Island, was a shipwright. In 1889 he was hired by George Stetson to build the 110-foor steamer Montesano and the tugboat Chehalis at Pope & Talbot's shipbuilding yard at Cosmopolis. Stetson later made Cooney a mill foreman, and under Chester White's leadership Cooney was promoted to superintendent and assistant manager. For most of his tenure as manager, White was headquartered at Seattle, while Cooney ran things at Cosmopolis. When White retired in 1914 (one source says 1911), Cooney, characterized as "a hot-headed Irishman" (Coman and Gibbs, 220), became manager of the Grays Harbor Commercial Company.

Pope & Talbot's Port Gamble was not only the first timber-industry company town in Washington Territory but also long considered one of the best, with good housing, decent wages, plentiful and nutritious food, and leisure-time amenities. Deserved or not, the reputation of Cosmopolis was very different.

"The Western Penitentiary"

Among the working men of the timber industry, Cosmopolis was known as "Neil Cooney's Empire" (Weinstein, 48). And worse. Cooney was fashioned the warden of the "Western Penitentiary," where thousands of workers came to "serve their time," earning low wages for perilous work (They Tried To Cut It All, 48-49). Most did not last long; the turnover was tremendous, but to the Grays Harbor Commercial Company and its labor recruiters, workers were simply a fungible, inexhaustible resource. Critics of Pope & Talbot's treatment of its workers were many and harsh. One wrote:

"Wages were low and they were kept that way … Labor was recruited steadily from Seattle, and the turnover was great … It was a low-wage heaven for skid-row down-and-outers and was known as such in every hobo jungle of the day … Cheap labor was needed, and Cosmopolis was organized to use it profitably, and that was all. Most of the work was unskilled, and all of it was dangerous. The food was the plainest, and low-paid Chinese cooks prepared it. Conditions were the poorest, and no money was spent by the company to improve them ...

"Every second that men worked and every ounce of labor expended had to pay handsomely; it was drive, drive, drive, every minute of every working day. The pressure in sawmills anywhere was severe; in the mills of Cosmopolis it was almost unendurable. It was designed to squeeze out of every man the utmost that he could give, then cast him out, often badly wounded in body and spirit. Few mill workers could stand it at Cosmopolis for very long" (Weinstein, 21-22).

Injuries and deaths were common and often reported in Seattle newspapers. Not atypical is an account from January 25, 1902, that appeared in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer: "Ira Dean, an oiler for the Grays Harbor Commercial Company's mill at Cosmopolis, was caught in a belt at the mill last night and literally torn into a hundred pieces, pieces of the body being thrown a hundred feet away" ("Oiler Caught in Belt").

A first-person account of conditions came from Egbert S. Oliver (1902-1989), a professor emeritus at Portland State University. He was recruited to work at Cosmopolis at age 14, and in a 1978 article in The Pacific Northwest Quarterly recalled:

"I did not know that the Cosmopolis mill was known to the mill-worker floating population of the Northwest as a place where the dregs of humanity could always find a job. It was said that the mill always had three crews, one coming, one on the job, and one quitting …

"The grub served in the large hall was ample in amount but largely inedible by civilized standards. The eggs were served hard-boiled so that the diner rather than the kitchen help would find the rotten ones. I saw one persistent man open three successive spoiled eggs at the table, the third having in it a half-formed chick. The man gave up, dropped his tableware, and left the table to vomit. I learned to survive. I learned that bread with the lardlike white margarine was edible and would satisfy hunger, that the skim milk served was usually drinkable, and that the potatoes boiled with the skins on were better than most egg or meat dishes" ("Sawmilling at Grays Harbor …" p. 2).

Local historian Edwin VanSycle (1902-1986), who was born in Cosmopolis, was unsparing in his criticism of Cooney and the Grays Harbor Commercial Company, but also noted:

"A man could always count on a job, a place in the messhall with 600 other men, and a place to sleep, but he would earn very little.

"The arrangement seemed to satisfy not only the company … but also many of the men themselves. An unexpected number stayed on to build homes and raise families in Cosmopolis. Others proved strangely loyal even in trying times, especially during labor unrest on Grays Harbor when strikers from other plants besieged the gates of the Commercial company plant in a vain effort to get the men to walk out. They never did. Even during the height of the I.W.W.’s (Wobblies) aggressive activity the Cosmopolis men clung to their jobs" (They Tried To Cut It All, 48).

The reference is to World War I, when the IWW and other unionists paralyzed the Pacific Northwest lumber industry. At Grays Harbor, strikers shut down all but one mill – the Cooney-run Grays Harbor Commercial Company at Cosmopolis. It may have helped that the mill had hired armed guards with dogs to patrol its perimeter fence.

A Softer Side to Cooney

Cooney became wealthy, and the company built him a showpiece home, a 10,000-square-foot mansion on a hill overlooking Cosmopolis, made entirely of lumber milled there and called, with false modestly, "the Spruce Cottage." But by the late 1920s the company was running out of owned timber and had to start buying from others. On July 30, 1929, a fire all but wiped out the city's downtown commercial core. The mill equipment was old and poorly maintained; the operation became unprofitable and deemed not worth salvaging. In 1931 it was all shut down. Cooney purchased the idle 500-acre site and would hold onto it until his death in 1943.

There was a certain strangeness to Neil Cooney. A praiseful short biography notes:

"With all his wealth and power, there was something terribly tragic in the life of this man. Childhood poverty, lack of education and environment combined to submerge him in his youth in the lower ranks of labor, fighting for survival. Later, as success began to crown his efforts, he became suspicious and fearful that his money was the attraction for some women. He loved little children and acknowledged that his big mistake in life was that he 'never married'" ("Neil Cooney 1860-1943").

But Cooney's last will and testament evidenced a deep affection for Cosmopolis and its people. He envisioned a new source of prosperity, leaving the property and a bequest of $100,000 to any company or person who would build a sulphite pulp plant of a designated capacity and put it into operation within seven months of his death. There were no takers. An offer by his executors to sell all the property to the city of Cosmopolis for $4,500 could not be financed (but provides further evidence that it was not a wholly owned company town). Another provision of Cooney's will was fulfilled – a bequest of sufficient funds to build an addition to Aberdeen's St. Joseph's Hospital, which treated many of those injured in the region's perilous mills.

Start Stop Start Stop

The Cosmopolitan mill site was purchased from Cooney's estate by Richard J. Ultican (1913-1971), who put in a new sawmill and built barges for the U.S. military during the later years of World War II. His mill was destroyed in a 1951 fire, and the site again sat idle. In 1957 Ultican sold his holdings to the Weyerhaeuser Company, which built and ran a pulp mill there until 2006.

The Weyerhaeuser operation was shut down in 2006 and in 2010 was sold to British investment banker Richard Bassett, with backing from the Gores Group, a California-based private-equity firm. The mill was restarted as Cosmo Specialty Fibers and produced dissolving pulp for the Asian market until the Covid pandemic forced its closure. It was restarted briefly, but all workers were laid off shortly before Christmas in 2022. Bassett became the sole owner, but as of 2025 operations had not been resumed. In 2024 the firm was fined $42,000 by the state Department of Ecology for allowing hazardous waste to accumulate on the property. That was only one of its liabilities.

"Cosi" Today

Even at the worst of times, the population of "Cosi," as Cosmopolis is known to locals, never fell below 1,000 after reaching that number in 1900. The 2020 census counted 1,638 residents, the highest up to that time. But according to former mayor Frank Chestnut, the closure of the Weyerhaeuser pulp mill in 2006 deprived the town of 65 percent of it revenue, much of which was not replaced during its brief revival.

At the time of this writing it remains questionable whether the pulp mill can be reopened. As reported in The Seattle Times in April 2025, "Cosmo Specialty Fibers has a long history of environmental violations, including tens of thousands in unpaid fees, discharge violations and industrial spills [and] still owes the state Department of Ecology hundreds of thousands of dollars for carbon emission allowances and unpaid air and water permitting fees" ("Cosmopolis on the Brink …"). Its lingering ecological threats will have to be addressed at some point, and repairs to make the pulp mill operational again could cost as much at $60 million.

Cosmopolis cut services and expenses to bring its budget out of the red, but Mayor Linda Springer told the Times, "We are operating on a very thin line. We are just hanging in there" ("Cosmopolis on the Brink …"). While its fate plays out, Cosi remained a pleasant place to live, with several public parks and the 18-hole Highland Golf Course. But it faced many challenges, in common with countless other small towns that didn't develop diversified economies. As summed up in the Times article:

"To stay afloat, Cosmopolis needs to reinvent its economy, current and past city officials say. They need tourism, retail, customer service — maybe they could attract a school or data center. Anything. Sure, they’d welcome the mill back. But their vision for the future can't rely on whether the facility … can be reopened" ("Cosmopolis on the Brink …").