When non-Native settlers arrived on Puget Sound in the 1850s they found bands of Native Americans in residence. Those living on the inland waterways came to be known as the Duwamish. The story of one Duwamish family – Jimmie and Jennie Moses, their relatives and descendants – runs for more than a century through the history of Renton, where their names are still honored.

Woods and Water

(Editor's Note: The names used here are for the most part the common English names adopted by some Native Americans. Even so, spellings may vary. Note that certain terms contained in the quotations may be objectionable.)

For many decades, members of the Moses family of Duwamish Indians lived in a rough dwelling near the once and no-future Black River, just to the west of today’s Renton High School. The land was wooded; the only street to ever run by the house door was the Black River, and that began drying up in 1916. When census folks came to enumerate the residents of Renton in 1900, they likely missed the humble home altogether. The family was not counted.

By all accounts the family of Jimmie and Jennie Moses was the last of the old Duwamish families living in the Renton area, once a group of several hundred Native Americans who had lived along the Black, Cedar, and Duwamish rivers for centuries. The coming of white settlers in the 1850s led to a diaspora of the Duwamish, both in Renton and throughout Puget Sound. Many were forced or encouraged to move to reservations; others moved to the big city (Seattle) or elsewhere to obtain employment when their traditional hunting and fishing grounds were encroached upon. The drying up of the Black River in 1916 due to the opening of the Lake Washington Ship Canal was only a final blow. Most of the Indians were gone by then. But the Moses family held out against these pressures and in doing so became an integral part of Renton history.

Long roots

The Moses family had long roots in the Renton area – roots deeper than those of the white settlers who supplanted most of their tribe. They were neither wealthy nor prominent in any of the usual senses, yet they were Renton royalty. As a remnant of the Duwamish Indians who once populated several villages in the area, the Moseses represented a not-so-distant past. While some early Rentonites might have preferred to forget the displacement of people that made room for their enterprises, others chose to embrace and celebrate the Moses family.

Unlike many of their relatives, Jimmie (ca. 1847-1915) and Jennie (1852-1937) Moses steadfastly refused to move to reservations provided by the government – at least until old age and poverty made them desperate. In this they were assisted by the protection of the influential Smithers family. The relationship between the two families was something between friendship and mutual benefit. Jimmie worked for Erasmus Smithers (ca. 1829-1905) on his farm and perhaps in a dairy, also. Likely he assisted Smithers in navigating his relations with Indians. He and his kin provided protection for Diana Smithers (1829-1894) and the children when the family patriarch was away from home. Some say that Jimmie Moses helped Erasmus Smithers find the coal seam that established his fortune and led to the platting of the Town of Renton in 1875.

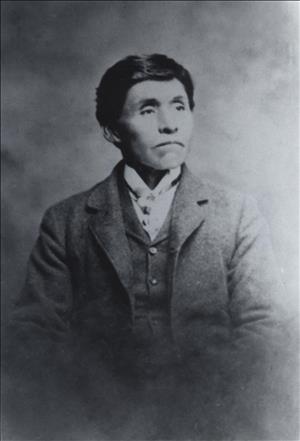

In tracing the history of these early families, it is difficult to separate fact from fable. Written accounts, both primary and secondary, and all written by non-Natives, can differ widely and are often highly colored. And even official documents, such as birth certificates and census records, are often misleading or simply wrong. It is not unusual to find three or four different birth years for a tribe member, on top of variations in names and spellings. In brief, Jimmie and Jennie Moses married about 1876 and settled along the Black River near other Duwamish. Jimmie’s father, Chief William Stoda (d. 1896), a distant cousin of Chief Si’ahl (1780?-1866), lived nearby, as did siblings and cousins. This lineage gave the Moses family a certain amount of prestige, even though the "chief" designation was not a Duwamish tradition, but one manufactured by the government.

There was much tragedy in the family. Jennie Moses had three sons who lived to adulthood: Joe (ca. 1882-1954), Charles (ca. 1891- 1919), and Henry (1900-1969); several other children died young, including a daughter who drowned in the Black River. Son Charles died of the Spanish Flu in 1919, one day after his sister-in-law Lillie, the young bride of Joe Moses, also succumbed to that epidemic.

As mentioned, Jimmie worked on and off for settler and town founder Erasmus Smithers and lived on land claimed by Smithers – land which had been Duwamish. Other indigenous people worked for Smithers, as well. Smithers’s daughter, Ada Thorne, recalled late in life: "Our little house was built on the only cleared place available, an Indian potato patch. Father taught the Indians agriculture. They planted and dug potatoes, mowed the hay, cradled and reaped the grain" (Thorne).

Tales tell of Smithers welcoming Moses and his family to continue living on his property, and even giving them the "papers" that would allow them to remain after his death. This story has many variations. Some say Smithers provided for Jennie Moses by granting her an acre of land in his will (despite the fact that Jimmie Moses outlived Smithers by a decade). A close reading of the Smithers will reveals no mention of the Moses family. Other say the "papers" came from homesteader James Tobin, whose widow Diana had married Smithers in 1857. However, Jimmie and Jennie were mere children at the time of Tobin’s death.

Whatever the answer, when son Joe Moses died in 1954, co-owning the property with brother Henry, probate records estimated his estate at $2,250, the half-interest on 1.8 acres. The house had burned down a few months earlier while Joe was hospitalized or living with Henry. Rumor has it that some boys playing with matches had caused the blaze. Henry Moses, at that time living on the Puyallup reservation, sold the land to the Renton School District.

Friends to All

From the number of testimonials in the files of the Renton History Museum, it appears that the Moses family was a friend to all and all were their friends. Several long-time Rentonites wrote of their adventures with the youngest child, Henry:

"Henry had two saddlehorses, Cricket and Fatty. The mare Fatty was broken to a buggy. I remember taking that horse and buggy to what we called Panther Creek which was near Springbrook. This creek was never over four feet wide, but during salmon runs would be full of salmon. We would gaff fish until we had a buggy load and then take them home to be dried and smoked. Many times these dried fish hung from the rafters in the house, and to me, at that time, they were quite pleasant smelling" (Mitchell).

Henry was also a standout athlete at Renton High School and in local leagues, playing baseball and basketball. Another bit of lore is that the high school teams took on the name Renton Indians in his honor. Accounts differ, as they do, as to whether the idea was Henry’s or another classmate’s. The name stuck until 2021 when it was changed to the RedHawks. No longer does the school’s fight song contain the cheer "Let’s scalp ‘em!" No more is the school’s paper dubbed The Talking Stick.

Jennie Moses is also recalled fondly by many residents. When she was widowed, and perhaps before, she kept body and soul together by weaving and selling rag rugs and through the charity of local businesses and neighbors. Her sons worked various low-wage jobs.

Despite their modest lifestyle, the Moses family elicited an astonishing number of honors and memorials. The funerals of both Jimmie in 1915 and Jennie in 1937 were events of public mourning, orchestrated and paid for by their white friends and neighbors. When Jimmie died, local businessmen collected 79 silver dollars to present to his widow. The Moseses were Catholic. News reports of Jennie’s requiem mass at St. Anthony’s described it as one of the largest ever held at that parish. An obituary in The Seattle Times reported that "The Pioneers of Renton knew her and the doors of their houses were always open to her. A visit from Jennie Moses was an event" ("Renton’s First Citizen").

Henry Moses came in for the lion’s share of tributes, both before and after his death in 1969. Perhaps because of his early fame in athletics, he was honored at a Henry Moses Night at Renton High School in 1968. A few years later, after his death, local merchants raised a totem pole at a shopping area in his honor. More properly called an honoring pole, this public artwork created by master carver Jim Ploegman can still be seen in front of the Fred Meyer on Rainier Avenue S in Renton. (The pole was stolen in 2009 and recovered months later in Oregon.) Friends also raised funds to help support his widow, Christina Moses (d. 1973). In 2001, the City of Renton included Henry Moses, "Last Chief of the Duwamish Tribe," in its sidewalk plaque project History Lives Here. The plaque featuring Henry’s likeness can be found at the corner of Lake Avenue S and S Tobin Street, near where the Moses homestead once stood.

Perhaps the most enduring honor was the naming of the city’s new swimming pool the Henry Moses Aquatic Center, despite the fact that Henry’s aquatic career was likely confined to the swimming hole in the Black River near his home.

Henry and wife Christina moved to Pierce County following his mother’s death in 1937, although they visited frequently. Joe Moses stayed on in the family home until shortly before his death in 1954. He, too, was active in sports in his younger years. Later he was a member of the Oldtimers’ Football and Baseball Club of Renton and a volunteer fireman. In 1952 he was honored at a meeting of the Renton Rotary where he was introduced as "Truly Renton’s first citizen." As happened with his parents, his funeral arrangements were paid for by some of Renton’s leading citizenry.

The Last of the Duwamish?

Folks like to refer to the Moses family as the last of the Renton Duwamish. While this is probably not literally true, they certainly were the last vestige of the Duwamish presence along the Black River. It is hardly surprising that, with the death of the Black River beginning in 1916 after the opening of the ship canal, the remaining indigenous people who had fished its waters moved on. Many had already been encouraged to move to the reservations at Port Madison on the Kitsap Peninsula (Suquamish Tribe), Whatcom County (Lummi Nation), and Auburn (Muckleshoot). Others merged into the general population. Even the Moses family, seeing the writing on the wall, began to consider the advantages of moving to a reservation.

Significantly, the Moses family played a role in the political history of the Duwamish in King County. Jimmie and his sons Joe and Henry were all at one time or another called "chief," an honorific title. Such designations aside, the Moses family did take an active part in efforts by the Duwamish Tribe for recognition, land, and treaty rights. Not only active, they at times took on a leadership role. A story for which we have no corroboration is that Jimmie Moses met several times with Governor Isaac Stevens (1818-1862) to negotiate treaty rights for his band of Indians, rights that had been written into the 1855 Treaty of Point Elliott. This nugget comes from a deposition Jennie Morris gave to government official, Charles E. Roblin, in 1917. While birthdates are often hazy, it appears that Jimmie was only a child at the time of the treaty wars. It is more likely that Jennie, with limited English skills, was referring to her father-in-law, William.

Chief William Stoda was the acknowledged leader of the Lake Fork Indians – those Duwamish who lived on the Black and Cedar Rivers. William and Jimmie were among the group who returned to the Black River without government permission after being displaced by the Treaty Wars of 1855-1856.

Another story, more grounded in reality, is that Chief William confronted officials sent to remove the remaining Duwamish families from the Black River about 1856. While the flowery speech attributed to him is likely highly paraphrased, the general purport – that they would not willingly leave the land where the bones of their ancestors were buried – is probably true. In fact, at least one account describes an Indian cemetery lying at the fork of the Black and Cedar rivers.

As the Duwamish found themselves scattered throughout Puget Sound, their chances of tribal recognition from the federal government dimmed. The fight for treaty rights has dragged on now [2025] for a century and a half. In 1915 a group calling itself the Duwamish Tribal Council (DTC) formed. In one of his final acts before he died that same year, Jimmie Moses submitted an affidavit asking for land allotments for his family. His statement, along with other Native leaders, including Charlie Satiacum and William Rogers, was published by the Northwestern Federation of Indians. In her 1917 deposition, Jennie Moses also asked for land allotments for herself and her children. None were received.

After Jimmie’s death, sons Joe and Henry stepped up. Joe, at that time about 33 years old, became a director of the DTC. The board also included one James H. Tobin, the half-Indian son of early Renton settler Henry Tobin. A federal report noted that Joe Moses and James Tobin were the only two of the 11 members of the board not living on a reservation.

Ten years later, the off-reservation Duwamish regrouped as the Duwamish Tribal Organization (DTO), an entity that exists to this day. Joe Moses served on the DTO council until his death, nearly 30 years. The fact that Joe served with both the DTC and the DTO is significant given that federal officials have endeavored to show no connection between the two organizations. Brother Henry Moses joined the council in 1944 and served until his 1969 death. From the late 1950s to the early 1960s, he acted as chair of the organization.

Both brothers were active members of the DTO. Joseph Moses took a lead role in dealing with the Indian Claims Commission, a federal body created in 1946 and charged with dispensing cash payments, but not land, to Indian tribes. In 1950 Joe Moses was a delegate to the annual meeting of the National Congress of American Indians which was held in Bellingham that year.

Perhaps most important, both Joe and Henry had a hand in approving membership applications to the Duwamish Tribe. Enrollment was and is a critical element of tribal sovereignty, ensuring that only true tribal descendants are eligible for negotiated benefits, if any, including money and allotments of land. An enrollment event took place at Liberty Park in Renton on July 1, 1951, a Sunday. Joe Moses and several other Duwamish leaders led the meeting, which reportedly drew some 300 Indians from throughout the county to Renton. Timing of the event was critical because the DTO had recently filed a multi-million dollar claim with the Indian Claims Commission for compensation for land taken from them in the nineteenth century. The Renton News Record provided front-page coverage of the event.

Justice came slowly and in small portion to the claimants. In 1963, the tribe was awarded $62,000. Another eight years passed before anyone saw a dime and then it amounted to some $64 per tribal member, according to the DTO.

The Old Ways

The Moseses were, in a sense, immigrants in their own land. Like many immigrant families, the children grew up with only limited knowledge of their parents’ culture. The boys could understand the native language, Lushootseed, but could not speak it. Spared the trauma of being sent to an Indian School, as many children on the reservations were, they still likely felt pressures to assimilate. However, there is plenty of evidence the family held on to some of the old ways, handing them down from parents to children. Many reminiscences of Henry Moses mention his "Indian" skills in fishing and canoeing. He himself told historian Morda Slauson that as a child he played with bows and arrows which he made. He also talks of seeing his father and others building a dugout canoe. According to friend Leonard Mitchell, "Henry filled a need for many boys. He was not only friend and companion, but was also a teacher. He taught me how to ride horseback, how to spear and gaff salmon, how to start a fire with wet wood, and he also taught me the Indian way to paddle a canoe" ("My Memories ...").

The Moseses built a smokehouse next to their home, a tradition that continues today on some reservations. "Whenever you could see blue smoke rising in the air, you always knew they were smoking salmon" (Littlefield). Oldtimers still recall Henry Moses and his skill at preparing fish for cookouts on the Cedar River attended by many Renton High School alumni.

"Somebody would dig a pit about probably three feet wide and maybe six or eight feet long and about a foot deep, and they'd build a fire and have that fire burn all night so that there were a lot of good coals. And then Henry Moses would come and he'd filet or butterfly the fish and run sticks through it, cedar sticks horizontally and one vertically, and then kind of weave those, poke it in the ground, and that fish was standing on its tail, and the fat would run down as the heat hit it, and then you'd pull the sticks out and of course, lay it on a table or whatever, and then cut the meat off the skin. And it was absolutely the most delicious fish in the whole wide world" (Verheul).

Jimmie Moses’s sister, Lucy Keokuk (1866-?), was a talented basket weaver. The Renton Historical Society is in possession of two of her prize-winning baskets.

A photo of Jennie Moses shows her wearing an ornate beaded arrow quiver (without arrows). According to Henry Moses, the quiver was given to her by Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce. While at first blush that might seem like a stretch, it is true that Chief Joseph (1840-1904) spent his final years on the Colville Reservation in Eastern Washington and visited Seattle in 1903. It is possible that mutual friends or relations put them in touch.

In February 1894, while there were still a number of Duwamish families in the Renton area, Jimmie and Jennie Moses participated in a unique cultural event: the Sing-Gamble. The Indian shaman known as Dr. Jack invited Indians from the Puyallup Valley to come and compete with the Black River and Cedar River Duwamish in a game of chance, one with similarities to the shell game, at his homestead on the Cedar River east of Renton. A white reporter attended the days-long event and published a dramatic, detailed, and more than a bit racist account in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, a story that was republished verbatim by historian Clarence Bagley in his book, History of King County, Volume I. Jennie Moses was apparently possessed by a demon during the fever-pitch happening – or perhaps was simply overcome by the cramped, hot, and smoky conditions within the dwelling.

"During the progress of the game on Monday the squaw of Jimmy Moses, a ponderous Indian woman, was suddenly taken ill, with symptoms of insanity. The game was not stopped even for a moment, but Doctor Bill was summoned and he immediately began preparations to drive away the evil spirit of which the woman was supposed to be possessed" ("Bet All They Have").

The observer goes on to recount the measures taken to free Jennie from the imp Tomomalies. After much chanting, dancing, and applications of boiling water to the shaman’s arms, Jennie was returned to her usual self and could be found carding wool for socks. A photo of the event shows Jennie Moses in Victorian-style dress observing the goings-on. Joseph Moses, about 12 years old at the time, may also have been present at this once-in-a-lifetime happening. A bit of living history found in the museum’s collection is a 1942 recording of Joe Moses singing an Indian chant in the language of his parents.